Should a former Philly bathhouse gain landmark status because of its place in LGBTQ history?

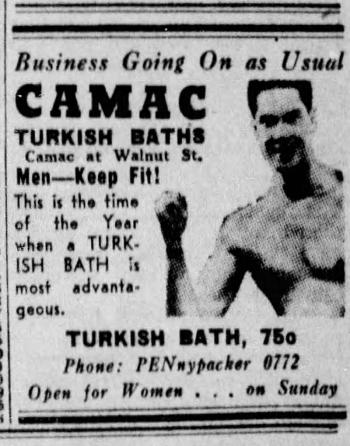

Back when homosexuality was illegal in Philadelphia, the Camac Baths offered a safe place for queer subculture to exist.

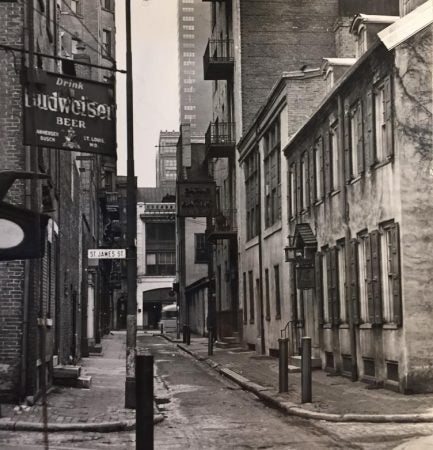

The 2014 S.12th Street site of the former Camac Bath. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Back when homosexuality was illegal in Philadelphia, the Camac Baths offered a safe place for queer subculture to exist. On April 12th, the Philadelphia Historical Commission will vote on whether or not to award landmark status to the Baths, a former Jewish schvitz that turned a blind eye towards gay patrons and became an underground “safe space” for white, gay men as early as the 1930’s.

As we approach the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots, there are still no landmarked buildings in Philadelphia recognized explicitly for their association with LGBTQ history. While the city has a number of strong connections to LGBTQ history, pairing those stories and events with existing physical buildings can be challenging in a rapidly developing city.

Just two years ago, a demolition permit was pulled for Little Pete’s Diner, a popular 24-hour spot on 17th Street, which also happens to have been the location of one of the first direct-action protests for LGBTQ rights. In 1965, at the Dewey’s Lunch Counter Sit-In, protesters stood up to the restaurant’s policy against serving LGBTQ patrons. The event is recognized by historians as a significant precursor to Stonewall, though two years ago when news organizations covered the pending demolition, only LGBTQ publications made the connection. More often, it was overlooked.

The beloved diner wasn’t architecturally notable. It sat beneath an open-deck parking garage, which undoubtedly helped generate support for its demolition, but a broader discussion around its historical significance was never raised by the local preservation community. In 2018, a historical marker commemorating the event was installed outside, but the lunch counter is gone forever.

Another 24-hour Dewey’s diner on the corner of 13th street and Chancellor was also a well-known gathering place for the LGBTQ community, a popular late-night spot in close proximity to the clubs in the Gayborhood. The low-slung, stone-clad circa 1955 restaurant building might have been a good contender for landmark status, but in 2014 it was demolished and replaced with condos.

Modest architecture, but cultural significance

Part of the challenge of recognizing sites of more recent cultural significance is that the traditional preservation framework isn’t always well-equipped to recognize sites of modest or low architectural significance, not to mention buildings that don’t meet the standard 50-year age mark, which is where advocacy efforts can step in.

Initiatives led by the National Park Service and National Trust for Historic Preservation seek to help navigate and resolve some of the common limitations, while underscoring the importance of recognizing LGBTQ heritage sites. Local organizations can also lead the charge. The Los Angeles Conservancy has been proactive in developing an LGBTQ Heritage initiative that confronts the inherent challenges around designation of these important cultural sites head-on.

An excerpt from the organization’s microsite on the topic reads, “While some of the places highlighted on this microsite have architectural importance, many are modest in appearance and require a deeper look beyond their facades to fully understand their stories and cultural value…these stories come alive and are much more meaningful when the physical building in which they occurred still exists.”

It’s worth noting that even the Stonewall Inn, which was designated a National Monument by President Barack Obama in 2016, isn’t a building of particular architectural significance. Yet it has become a deeply significant cultural landmark representing the struggle for LGBTQ rights because of the power of the events that occurred there.

Defining integrity

Fortunately, Philadelphia’s Historic Preservation Ordinance is well equipped to distinguish between cultural significance and architectural significance, even if it hasn’t typically been interpreted to that effect. Compared to the National Register’s four, it offers ten generous criteria under which a nominator may build a case around a place’s significance, a number of which focus on association with cultural movements or events in history, unrelated to physical architectural form.

This should be good news for Camac Baths which were nominated for their connection to the “cultural, political, economic, social, and historical heritage of the community,” specifically an association with the Jewish immigrant population and with Queer subculture.

Still, the Commission’s staff comments on the properties’ nomination, put forth by the Keeping Society of Philadelphia, puzzlingly suggest that they are self-imposing a strict integrity requirement. The staff report, appended to the beginning of the nomination form, concludes, “The three structures included in the nomination, which were not purpose built as either a bathhouse or clubhouses, have lost any historic character and integrity they may have had from their many unsympathetic alterations Owing to their lack of integrity, they fail to inform the public of any historical significance they may have had and therefore fail to qualify for designation.”

“Integrity,” in a preservation context, refers to a building’s ability to convey its significance through retention of important characteristics or qualities such as location, design, setting, feeling, and association. Philadelphia’s Historic Preservation Ordinance doesn’t explicitly require proof or consideration of integrity, though the Commission has, in the past, opted to impose one. Still, the very concept of integrity is, like many aspects of preservation, subjective.

The Camac Baths, located at the Southeast corner of Chancellor and Camac Streets, was never a purpose-built bathhouse. Built in the early 20th century as a manufacturing or warehouse building, the simple, brick structure was converted to a bathhouse in 1928 and operated until 1984. Though the exterior of the building is relatively modest, it still retains some of the detailing from its time as the Baths, particularly on the interior. It is included as a contributing building within the East Center City National Register Historic District, which was reassessed in 2017.

Not only does the Commission staff’s interpretation impose non-existent requirements of architectural integrity, it also doesn’t address the specific cultural context of LGBTQ heritage. At a time when it wasn’t safe to express gay sexual identity, part of the overall appeal of a place like the Camac Baths, might have been that it was under-the-radar. All too often, very little documentation or records of early LGBTQ history survives simply because leaving a record was a liability.

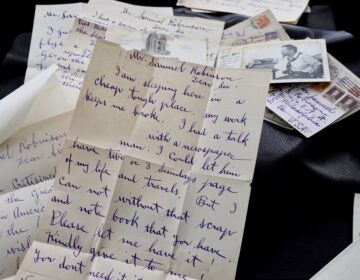

According to the site’s nominators, the ability to connect such early accounts of homosexual activity is part of what makes the Camac Baths stand out. The nomination is backed by research by scholar Marc Stein, author of City of Sisterly and Brotherly Loves: Lesbian and Gay Philadelphia, 1945-1972, including first-hand accounts. The Baths were also a favorite haunt of well-known gay author Christopher William Bradshaw Isherwood, who lived in the area in the early 1940s and wrote about time spent there in his diaries, including a day-long visit with a Mexican ballet dancer.

As Oscar Beisert of The Keeping Society puts it, “Camac Baths was never ‘gay.’ It was a place that appears to have turned a blind eye to men who had sex with men…a hiding place for people who weren’t allowed to exist.” Specifically, they were a place where white, closeted, and openly gay and bisexual men could engage sexually without fear of retribution.

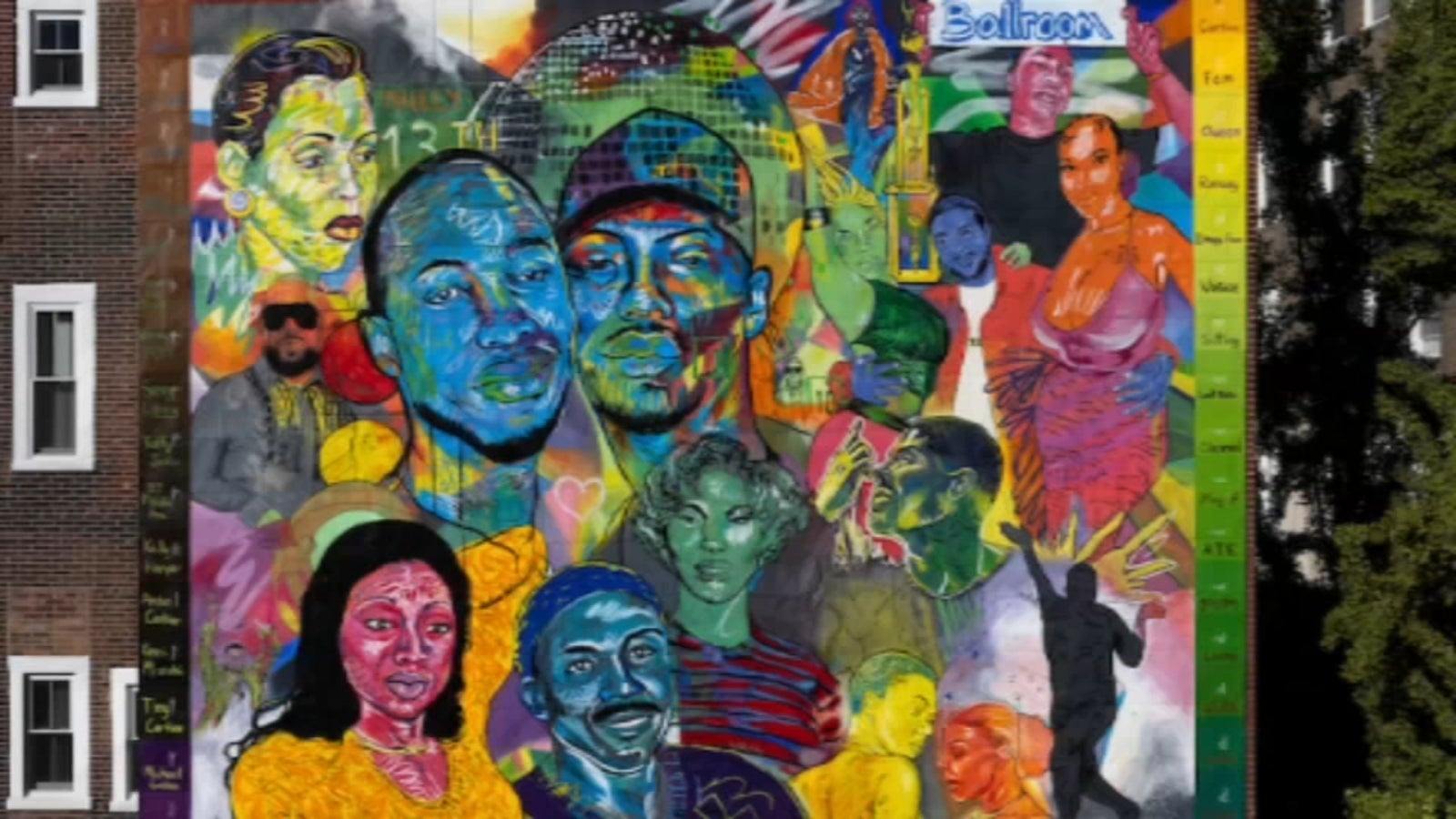

As the nominators acknowledge, it’s important to point out that the Baths were initially segregated. Many intersecting axes of identity affect and shape specific histories, even within marginalized communities. As an early example of underground gay culture in the United States, the Baths were a space that only a limited segment of the LGBTQ population had access to.

The nomination was recommended by the Committee on Historic Designation in February. At least two letters of support have been submitted on behalf of the nomination, one by John F. Anderies, Director of the John J. Wilcox Jr. Archives at the William Way LGBT Community Center and another by the Board members of The Rainbow Heritage Network.

When contacted for comment, Paul Chrystie, Deputy Director of Communications for the Philadelphia Historical Commission, responded that “the Commission as an entity does not comment on nominations other than through their votes to designate or not, based on whether a resource satisfies the criteria for designation.” Representatives for the Preservation Alliance of Greater Philadelphia plan to attend Friday’s meeting in support of designation; however, they do not wish to comment at this time.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.