SEPTA touts $3B economic impact as agency preps for bruising budget battle

SEPTA officials laid the groundwork for upcoming budget battles on Thursday, releasing an economic impact study that frames the transit agency as a critical cog in the region’s economy and profitable investment for state lawmakers.

The study, prepared by Econsult Solutions, argues that Southeastern Pennsylvania is the Commonwealth’s economic engine. Nearly a third of the state’s population lives in the region, generating 41 percent of Pennsylvania’s economic activity on just five percent of its land. And without SEPTA, the report asserts, that engine would grind to a halt.

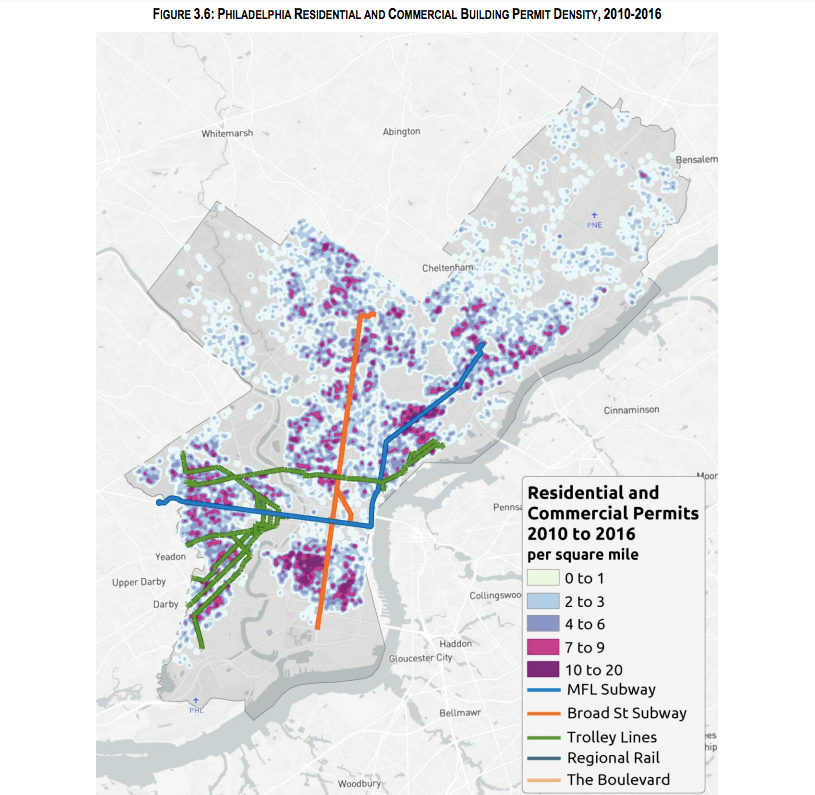

If not for Southeastern Pennsylvania, the state’s population would be shrinking. The region’s five counties grew by 81,565 residents between 2010 and 2016, while the rest of the state lost a collective 9,861. Philadelphia accounted for nearly half of that increase, and the census tracts adjacent to the Broad Street and Market Frankford Lines saw a 31,423 jump, or 43 percent of Pennsylvania’s population increase. Beyond its role as a driver of growth, the transit agency itself produces $3 billion in annual statewide economic impact, the SEPTA-commissioned study said.

But like a Philadelphian waiting for the bus, SEPTA looked down the road to see what’s coming their way, and what the agency saw could be problematic, officials said.

SEPTA faces two major funding challenges in the coming years: maintaining the existing system and expanding it to meet future needs.

Come 2022, the toll revenues generated on the Pennsylvania Turnpike and delivered to the state’s transit agencies will drop from $500 million to $50 million. SEPTA gets around 70 percent of the state’s transportation capital funding, so unless Harrisburg re-allocates money, SEPTA could lose around $315 million-a-year for major construction and equipment needs.

“That drop there is supposed to be an increase in the general fund,” said Jeff Knueppel, SEPTA’s general manager. “But, that’s tough — there’s always a budget battle here in our state.”

The passage of Act 89 in 2013 raised Pennsylvania fuel taxes to pay for increased infrastructure spending, boosting SEPTA’s annual capital funds by about $210 million. In the five years since, SEPTA has managed to start crossing items of its need-to-fix list; seeing the capital budget reduced to pre-Act 89 levels would lead the maintenance backlog to start growing again. Eventually, that would mean more downed catenary wires and broken-down buses, and maybe even significant reductions in service.

Econsult credits the $775 million in SEPTA capital spending since Act 89’s passage for 5,420 jobs, paying $302 million in earnings, across the Commonwealth. Those figures include direct impact — the SEPTA employees and contractors directly employed on projects, plus the knock-on effects of their employment and SEPTA’s purchases — but exclude the businesses and workers who rely on the transit agency for transportation. Even if SEPTA manages to maintain its capital budget, the transit agency won’t be able to maintain increasing rail ridership trends without money to expand service. While bus ridership has declined significantly in recent years, ridership on SEPTA’s trains and trolleys has gone up, fueled in large part by the more than 51,000 new jobs and numerous residential developments that have transformed Center City over the last decade. As the city’s population continues to grow, new office towers continue to rise, ride-hailing won’t be able to move enough people effectively, so transit ridership capacity needs to keep up, said Econsult’s President, Dick Voith.

“Uber and Lyft, they provide a great service to people, but they don’t support what’s driving the value and growth in the city and the region to the level that you need,” said Voith. “Public transportation is absolutely crucial, density is crucial — cars take up a lot of land, a lot of space, [and] we don’t have it.”

Knueppel roughly estimated a needed increase of $6 billion in the coming years to cover expansion projects, ranging from the Norristown High Speed Line extension to King of Prussia, to modernizing the city’s trolleys.

Knueppel also mentioned SEPTA’s hopes of one day running eight-car trains on the Market Frankford Line. The El currently runs six-car trains. To accommodate the longer trains, some station platforms would need to be lengthened, additional cars purchased, and the railcars’ maintenance and storage facilities would need to be expanded. “We’ve had a 41 percent increase in ridership [on the El] going back to 1988,” said Knueppel. “Doing this project, and [reconfiguring the seating layout on El railcars], would give us another 41 percent.”

Convincing state lawmakers in 2013 to increase gas taxes to cover repairs and improvements to Pennsylvania’s transportation infrastructure wasn’t easy — Act 89 only passed by six votes. But, as SEPTA officials are quick to noted, no one who said ‘Aye’ lost reelection immediately after. The voters, the argument goes, have accepted paying a bit more at the pump for smoother roads, stronger bridges, and more dependable public transportation. Most of the Econsult report aims at demonstrating how responsible SEPTA has been investing their Act 89 windfall, and the kind of dividends those capital projects have paid, countering critics’ characterization of public transit as welfare.

Armed with these favorable figures, SEPTA officials hope they’ll be able to convince Harrisburg to maintain their overall funding levels when toll revenues dry up. But even with a scoresheet of supportive stats, SEPTA knows it’ll be hard to get the kind of budget increases needed to expand capacity. And under President Donald Trump, the U.S. Department of Transportation seems more focused on funding rural and ex-urban infrastructure than metropolitan rail projects.

So, SEPTA may look to the five-county region for financial support in the coming years. “It maybe more of a regional issue though, than something that’s the state,” said Knueppel. In the coming weeks, SEPTA will present the study’s findings to the region’s county commissioners and city officials in Philadelphia.

“We’re worried about our ability to keep supporting all this economic development,” said Knueppel. “There’s a lot going on in our city and in the suburbs right now, and on our rail network, it’s pushing us to the limits of our capacity.

“We have to look,” he added. “The region has to get together and figure out what to do.”

Currently, local governments don’t directly contribute much to SEPTA’s budget, which comes mostly from the state. (The region does, however, generate 36 percent of the total tax revenues to the Commonwealth’s general fund). For the coming fiscal year, SEPTA expects to receive $11.75 million from the local counties for capital projects — about 1.5 percent of the $750 million total. The five counties will also contribute $105 million for operating funds, making up 11 percent of SEPTA’s total operations budget.

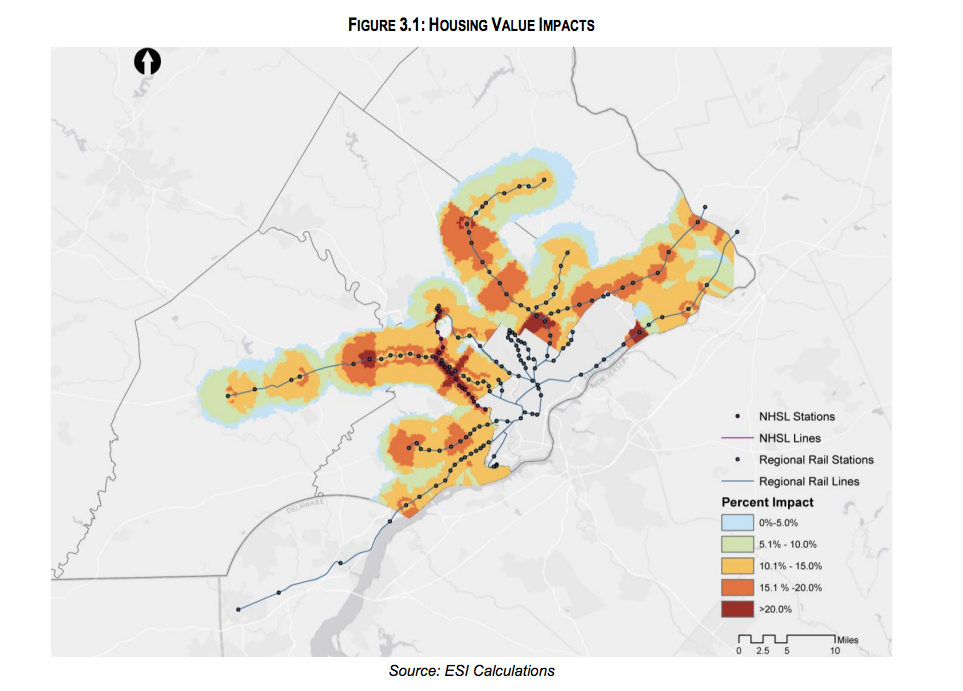

The Econsult report, for which SEPTA paid $120,000, couched the transit agency’s value to the suburban counties in terms of residential property values, calculating that proximity to SEPTA Regional Rail or Norristown High Speed Line stations adds 7.4 percent to suburban home values.

Still, if SEPTA does end up asking local governments to bear more of the financial burden, the agency may find itself getting in line. Philadelphia recently took back control — and fiscal responsibility — of its school district. In the suburbs, hundreds of bridges and roads still need major repairs. And everywhere, growing pension obligations eat up a larger share of budgets.

As the region’s leaders consider SEPTA’s funding needs, they shouldn’t look at it as what the transit agency’s requesting, argued Econsult’s Voith. “Really, what the region should be thinking is: What investments do we need to make? It’s not just an ask, it’s an investment,” said Voith. “When we do studies, we don’t go with a preconceived answer. When we look at this, we really believe that the investment return is there.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.