SEPTA riders overwhelmingly take the bus and subway. Why does Regional Rail receive more funding?

SEPTA’s Regional Rail network has been running on borrowed time. It carries about 11 percent of SEPTA straphangers in an aging fleet of rail cars, on legacy infrastructure with the system’s most pressing repair needs. Of late, Regional Rail has also received the lion’s share of SEPTA’s capital budget and has been instrumental in building broad-based political support for increased transit funding. Jim Saksa reviewed 10 years of SEPTA spending to understand why Regional Rail is a regional priority – and why that might just make sense.

Six votes.

In 2013, SEPTA avoided a doomsday scenario by just six votes. If Harrisburg couldn’t pass a new transportation funding bill, the future looked grim: nine Regional Rail lines abandoned; trolleys replaced by buses; traffic-choked roads flooded by 90,000 former transit riders across the region.

To hear the authority say it, SEPTA—the entire region, really—was saved by those six representatives in the Pennsylvania House who switched from nays to ayes between the first losing vote on Act 89 and the successful second. “It was all about doing what’s right for this region,” and in turn the Commonwealth, said SEPTA Assistant General Manager for Government and Public Affairs Fran Kelley.

SEPTA’s most urgent current capital needs center on the Regional Rail system, and regional legislative support to meet that demand was instrumental in Act 89’s passage.

SEPTA didn’t get the $420 million a year it said it needed from the Commonwealth, but what it did get — around $330 million a year, up from $120 million a year before the act’s passage — has proven enough to keep the trains running and the bridges standing.

SEPTA does not let a single groundbreaking go by without thanking Act 89.

Since its passage, SEPTA has launched a host of infrastructure overhauls, replacing the substations and catenary wires that power Regional Rail trains, increasing parking options at overstuffed suburban stations, and upgrading Regional Rail safety systems per a federal mandate other railroads ignore. Given the comparative paucity of projects to improve life for bus passengers, it sometimes seems like Regional Rail gets all the new funds.

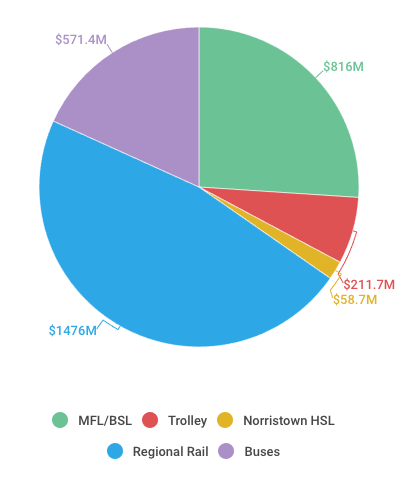

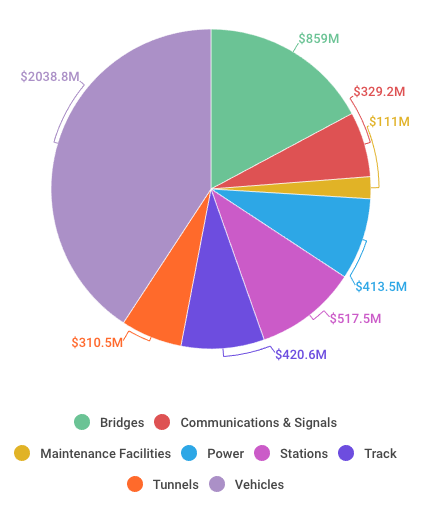

In fact, Regional Rail has received a plurality of SEPTA’s capital funds over the last ten years: 37.66 percent of the $3.92 billion in total capital expenditures between fiscal years 2007 and 2016.* In the past decade, $1.48 billion has been spent repairing tracks, upgrading signal systems, fixing stations, maintaining electrical grids, overhauling old trains and buying new ones.

All of this investment doesn’t stop Regional Rail riders from wondering why SEPTA isn’t spending more to improve their service. Last summer, Regional Rail riders cursed SEPTA when a widespread defect put a third of its railcars out of service. Frustrations boiled over as Regional Rail lines were bedeviled by overcrowded, late, and canceled trains.

SEPTA provided PlanPhilly with data for the last 10 years showing what the authority spends on each mode. Still, SEPTA Deputy General Manager Richard Burnfield warned that not even a decade of data provide a full picture of how the authority has spread its capital dollars. “Given that investments are expected to last 30 to 50 years, the longer you look, the truer sense you have of the investments that you make in the different modes.”

Take, for example, SEPTA’s half-billion dollar investment to rebuild the “Frankford side” of the Market-Frankford El, between the 2nd Street Portal and Frankford Transportation Center starting in 1988, followed by another $734.7 million to rebuild the El from 44th to 69th Street stations. Those huge, once-in-a-generation outlays are only partially reflected in the 10 years of data reviewed by PlanPhilly (around $400 million in those costs accrued during the decade reviewed). Similarly, large future expenditures, like SEPTA’s planned trolley modernization project and potential extensions of the Broad Street Line or the Norristown High Speed Line (NHSL), aren’t included.

REGIONAL AUTHORITY, REGIONAL SPENDING

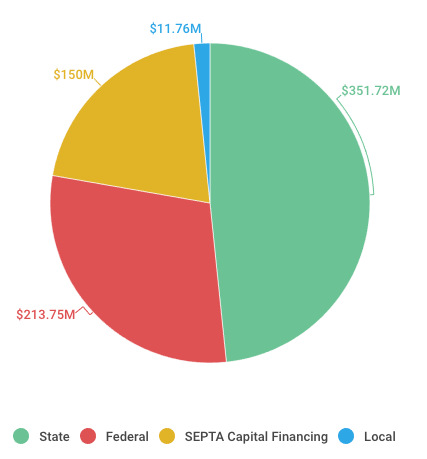

SEPTA officials like to emphasize that they operate a regional public transit system. “If you look at SEPTA, it’s truly a regional authority with a regional board of directors looking to do what is in the best interest of the region and the Commonwealth,” said Kelly. That regional focus shows itself in where SEPTA spends its capital dollars, which come overwhelmingly from the state and federal government.

If SEPTA was trying to get the most ridership bang for its capital buck, Regional Rail would not be the way to go.

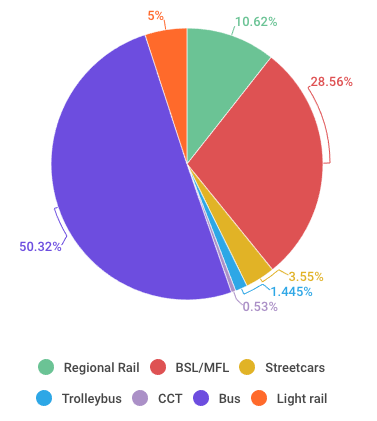

While Regional Rail ridership has increased about 50 percent since 2000, it accounts for just 10.62 percent of all SEPTA riders during the past decade (and just 11.5 percent of ridership in the fiscal year ending June 30, 2016 — just before the Silverliner V fiasco). Over the same period, buses recorded 1.76 billion unlinked trips (the number of times riders stepped on a SEPTA vehicle, counting separately multiple boardings to a destination), accounting for more than half of SEPTA’s ridership. But over the last decade SEPTA spent just 23 percent of its capital funds on buses — 14 percent, or $571.4 million, less than the amount invested in Regional Rail.

SEPTA’s two heavy rail lines, the Broad Street Subway and Market-Frankford El, fared a bit better. For carrying 964.4 million riders over the last 10 years (28.6 percent of unlinked trips) these lines got $816 million in capital funds (20.8 percent of total capital expenditures). SEPTA spent another $211.7 million on its trolley lines and $58.7 million on the NHSL, which combined to provide 288.6 million trips, for the same period.**

Broken down into per-trip figures, SEPTA spent $4.12 in capital expenses per unlinked trip on Regional Rail, but just $0.85 for heavy rail and a mere $0.51 per trip on buses. (Public transit agencies commonly use per-trip costs as a measure of financial efficiency.)

Capital expenditures show just one half of SEPTA’s spending equation. Like most local governmental entities, SEPTA splits its budget into two: a capital budget, which covers all major expenditures like new vehicles or infrastructure replacement projects, and an operating budget, which covers all of the day-to-day costs, like labor, spark plugs and the electric bill.

Looking at operating expenses, Regional Rail comes out on top again. SEPTA spent $2.8 billion on its railroad division during the last 10 fiscal years, compared to just under $9 billion across the rest of SEPTA’s operating divisions. That works out to $7.84 spent per trip on Regional Rail, compared to $2.98 per trip across the rest of SEPTA’s modes.

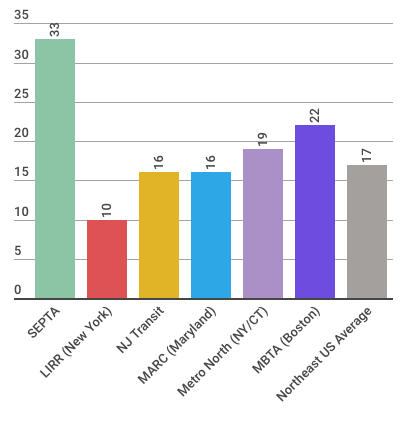

While $7.84 per Regional Rail trip sounds expensive relative to SEPTA’s other modes, it actually fares well compared to other commuter rail providers, which spend an average of $11.73 per trip on commuter rail.

SEPTA also spends less on its other transit modes than the national average in 2014, the most recent year surveyed by the American Public Transportation Association. In operating expenses alone, SEPTA spent $1.91 per trip on the subway and El in 2014, compared to $2.20 nationally, and $3.49 per bus trip, $0.57 less than the national average.

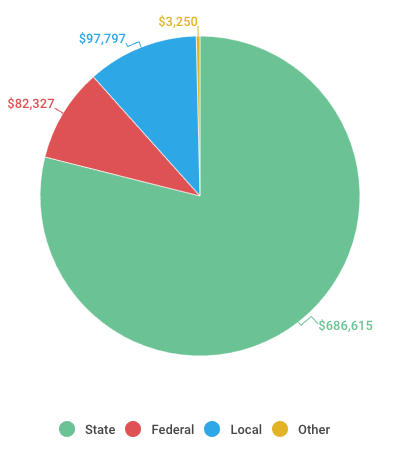

Regional Rail punches above its ridership weight when it comes to operating revenues, thanks to more expensive fares and higher rents from station-based shops. Over the FY07-16 period, SEPTA earned $1.45 billion in railroad revenues, almost 30 percent the total operating revenue haul of $4.86 billion. The rest of SEPTA’s operating budget ($6.94 billion over the last decade) came in the form of taxpayer subsidies, with the Commonwealth supplying the lion’s share (around 79 percent last year).

Taking all of this into consideration — operating expenses, capital expenses and revenues over the last ten years — each trip on Regional Rail cost taxpayers $7.90. Across all other modes, the subsidy was just $2.51. Like taxpayers deducting the interest on their mortgages and student loans, middle-class, suburban Regional Rail riders receive subtle government support far larger than their poorer, bus riding peers.

WHY REGIONAL RAIL SEES MOST OF SEPTA’S CAPITAL DOLLARS & (MAYBE) WHY IT SHOULD

Why is SEPTA spending more on Regional Rail than its other modes right now?

It’s tempting to point to SEPTA’s governance structure: Philadelphia gets just two board seats, the same as each of the four suburban counties. Such explicit power disparities arguably reflect inequalities along the woven lines of class and race: It’s no secret that the suburbs are generally wealthier and whiter than the average straphanger in the city.

SEPTA, of course, disagrees with this political analysis. But so too does the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission’s (DVRPC) Associate Director for Transportation, Greg Krykewycz, who said the truth is much simpler.

“Construction happens where the stuff happens,” said Krykewycz. Most of SEPTA’s infrastructure — tracks, signals, catenary wires, substations, etc. — serves Regional Rail, and most of that system lies outside Philadelphia. SEPTA “is a big system with a lot of legacy infrastructure and three-fourths of the stuff… is in suburban locations, as opposed to city locations.”

According to DVRPC, approximately 66 percent of SEPTA’s tracks (Regional Rail, light rail, and trolleys) are located outside the city limits, and 64 percent of SEPTA’s train stations are in the suburbs.

When SEPTA stumped for state dollars a few years back, it pointed towards a $5 billion backlog of required maintenance. While vehicle replacement was the largest financial need, it wasn’t as pressing, SEPTA official say, as work on bridges, tracks, signals, and power systems on Regional Rail.

During the Act 89 negotiations, SEPTA was able to point in particular at Regional Rail bridges to convince lawmakers to back the bill. According to SEPTA’s former general manager Joe Casey, as much as elected officials love it when new infrastructure is built in their districts, they hate to see old infrastructure fail. SEPTA made the risk abundantly clear. “It wasn’t Chicken Little, y’know, the sky is falling,” Casey said at a recent infrastructure conference at Drexel University. “It was really legitimate.”

SEPTA brought politicians onsite, said Casey, to “show them a support beam on a bridge and show them a ten-inch gap where it’s supposed to connect.”

“I think that was really eye-opening for some elected officials.”

Last year, SEPTA finished major repair work to the Crum Creek Viaduct, a 117-year-old bridge that carries 57 trains every weekday on the Media/Elwyn line. It was one of the authority’s first major infrastructure projects fully credited to Act 89. Without the funding, SEPTA faced suspending all service on the line.

SEPTA says it allocates funds apolitically, based on need. “State of good repair” comes first, said Burnfield, followed by safety improvements and then capacity upgrades.

The Regional Rail system was cobbled together from a handful of dead transit companies, and one side effect of that legacy is that those businesses spent their dying years forgoing infrastructure maintenance and upgrades. The Crum Creek Viaduct and the recently rehabbed Whiskey Run Bridge are just two of SEPTA’s 121 centenarian spans, most of which support Regional Rail tracks. Most of those are located in Delaware County, where the terrain isn’t as flat as in other counties and therefore requires more bridges and viaducts. That’s why SEPTA’s foreboding no-funds forecast hit its southern lines the hardest.

As of 2013, Regional Rail still relied on some of its original power infrastructure — meaning the trains relied on the same substations and catenary wires — built when railroads first electrified in the 1920s and 30s. Regional Rail is just due for some TLC.

As Krykewycz puts it, Regional Rail is emerging from “a long period of time kind of running on rubber bands and bubble gum.”

There is also just more of Regional Rail than there is of SEPTA’s other fixed rail systems. SEPTA does not have to pay to build and maintain the pavement on which its buses run, which significantly reduces its capital spending price tag. But SEPTA does pay for the 609 miles of track it operates on, more than 73 percent of which are Regional Rail (this includes Regional Rail tracks leased from Amtrak and baked into SEPTA’s capital budget).

Echoing SEPTA officials, Krykewycz emphasized that SEPTA was more than just the sum of its parts. “It’s hard to slice the benefits out — city vs. suburb, county vs. county — because it’s an integrated regional system.” said Krykewycz. “If you’re talking about Regional Rail service, it’s not just benefiting city riders because you’re maintaining a regional, suburban constituency for transit. It’s also benefitting city riders because Regional Rail is primarily carrying peak hour commuters that would otherwise be driving into the city, and choking up city service streets and slowing up all the buses.”

While the city and suburbs have fought over SEPTA allocations in the past, relations have been relatively cordial over the last few years. But not everyone thinks the status quo is copacetic.

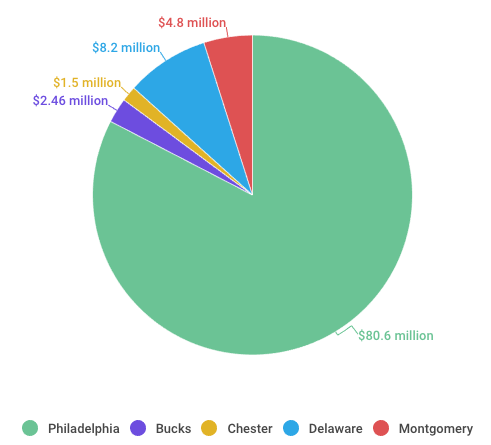

During Philadelphia’s budget hearings this year, Councilman-at-large Allan Domb noted that the suburbs contribute far less in direct funds to SEPTA’s operating budget. This year, Philadelphia will chip in $80.6 million in local subsidies. The rest of the four counties combined will contribute just $17.1 million (Bucks: $2.46 million; Chester: $1.5 million; Delaware: $8.2 million; Montgomery: $4.8 million). “It sounds like the suburbs are taking advantage of us,” said Domb, noting that Philadelphia covered around 83 percent of SEPTA’s local operating subsidies. “That’s not fair to Philadelphia.”

Not so, testified SEPTA General Manager Jeff Knueppel, who said the city agreed to a larger funding burden decades ago following fierce negotiations among the counties. Most of SEPTA’s operating subsidy comes from the Commonwealth (78.9 percent). The local subsidies make up just 11.2 percent. As a whole, Southeast Pennsylvania contributes an outsized share of tax revenues to Harrisburg, with a majority of the regional share coming from the burbs. City Transit ridership made up around 81 percent of all SEPTA ridership last year. And, as Knueppel noted to PlanPhilly at the council hearing, Philadelphia gets to tax the wages of suburban-based commuters.

Delaware covers the cost of SEPTA operations in the First State. New Jersey gets a free ride, chipping in nothing.

Even if SEPTA is spending disproportionately more on Regional Rail, the other modes are still seeing improvements. Over the last five years, Burnfield said, SEPTA increased the size of its bus fleet by about 100, including 30 more articulated, 60-foot buses. Last year, SEPTA entered into a five-year contract to buy 525 buses. SEPTA has also begun the slow process of replacing its ancient streetcars with larger, modern articulated trolleys — a project that will take years of planning and engineering before more than $700 million can be spent overhauling SEPTA’s tunnels, building new stops, and buying new vehicles. And work recently began on one of the agency’s most audacious overhauls — City Hall Station, where SEPTA will need to remove and replace walls under the world’s largest municipal building.

And yet, an argument can be made that SEPTA is not spending enough on Regional Rail.

SEPTA uses 396 rail cars on its 13 Regional Rail routes. Of those, 231 are Silverliner IVs delivered between 1974 and 1976, and 45 are push-pull cars (unlike the self-propelled Silverliners, these rely on a locomotive) built by Bombardier in two batches (1986 and 1999). Nearly 60 percent of SEPTA’s Regional Rail fleet is over 40 years old — considered the end of a rail car’s useful life — and replacing these cars will cost over $1 billion. SEPTA expects to begin buying the next railcar generation in 2023, after it wraps up delivery on 45 new multi-level railcars.

SEPTA regularly overhauls its vehicles to extend their functional lives, but even with the most meticulous maintenance, the years take a toll. Regional Rail runs on borrowed time.

In the fiscal year that ended June 30, 2016—before a widespread defect put a third of SEPTA’s Regional Rail fleet out of service—rail cars broke down every 23,352 miles. That itself is a 57 percent decline from just three years earlier, when Regional Rail cars averaged 56,683 miles between mechanical failures. In its latest operating budget, SEPTA lowered its expectations, hoping to make it just 25,000 miles between breakdowns.

SEPTA’s commuter rail peers perform much better. In its “cautionary tale” on New Jersey Transit, the New York Times noted that its trains “break down about every 85,000 miles, a sharp decline from 120,000 miles between breakdowns four years ago.” The Times compared that unfavorably to New York City’s other two commuter lines, the Long Island Rail Road and the Metro-North Railroad, which travel more than 200,000 miles between breakdowns. SEPTA’s commuter rail trains were more than eight times less reliable.

That drop in reliability has shown itself in Regional Rail’s on-time performance, which dropped from 92.6 percent in fiscal year 2013 to 83.8 percent in fiscal year 2016.

THE TIES THAT BIND

Many of SEPTA’s most expensive challenges really are regional, and that’s one reason why Act 89 ultimately passed. SEPTA told the Senate Transportation Committee of its $5 billion backlog of deferred maintenance, $4 billion affected Regional Rail. Spreading the predicted pain across the five-county region paid political dividends: 53 of the region’s 66 state representatives voted for Act 89.

Local GOP support proved critical. Corbett’s originally proposed a $1.9 billion bill that offered very little in the way of funding public transportation. In the state Senate, transportation committee chair John Rafferty (R-Montgomery) pushed through a larger, $2.5 billion version that included hundreds of millions for transit. SEPTA, by far the largest of Pennsylvania’s 18 public transit agencies and the only one with a substantial rail network, receives most of Act’s $480 million a year in public transportation funds.

Such a stately sum rallied rural Republicans in opposition. When Rep. Brad Roae (R-Crawford) accused SEPTA of wasting state funds on bus driver wages, another Republican, Rep. Tom Killion (R-Delaware/Chester), a former SEPTA board member, argued in a letter that the union contract actually saved the authority money. Killion’s support drew the ire of Rep. Daryl Metcalfe (R-Butler), who dismissed SEPTA’s dire warnings, and called the public transit authority “just more welfare.”

Nobody’s fool, SEPTA’s Fran Kelly credited the leadership of his boss, board chairman Pat Deon, a Republican fundraiser from Bucks County. “Time and again, Chairman Deon said this is about working together as a region and not getting mixed up with the labels — who has a R or D next to their name,” said Kelly.

Without SEPTA, Philadelphia would grind to a halt. But so too would the suburbs. Regional Rail stitches southeast Pennsylvania together, keeping it a functioning whole. One can argue with a straight face that, without those ties, SEPTA’s center — Philadelphia — cannot hold.

*NOTE: In calculating figures to compare capital spending by mode, PlanPhilly has excluded $451.766 million in capital expenditures SEPTA classified as “Multimodal” funds. These funds paid for the purchase and repair of utility vehicles, SEPTA Key, non-mode-specific communications equipment, intermodal station upgrades (including parking), police equipment and real time information systems.

**NOTE: The Media/Sharon Hill (Routes 101 and 102) trolleys and Norristown High Speed Line are considered ‘light rail’ under the Federal Transit Administration data used by PlanPhilly for ridership totals, whereas the remainder of SEPTA’s trolleys are considered ‘streetcars’. SEPTA’s capital expenditure data lumped the Media/Sharon Hill routes with city trolleys, but not the Norristown High Speed Line, which SEPTA accounted for separately.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.