Revolutionary War army comes to life in newly discovered painting

The Museum of the American Revolution displays a newly acquired, 7-foot watercolor of the Continental Army, circa 1782, that was painted from life.

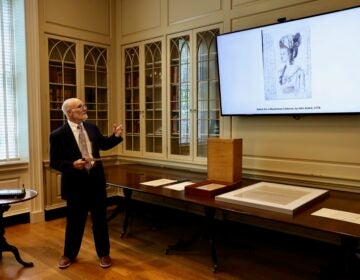

Museum of the American Revolution educator Dan Center identifies landmarks in a 7-foot-long painting by Pierre L'Enfant. It is the only known depiction of George Washington's headquarters tent in use in the field. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Last year at an auction in Texas, the Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia bought a painting depicting George Washington’s army camped along the Hudson River for $12,000.

The watercolor landscape is a long, narrow strip — 7 feet long and just 9 inches high — showing the scope of Washington’s Continental Army. It had been attributed, without verification, to army engineer and architect Pierre L’Enfant.

When the museum curators brought the painting home to Philadelphia, they discovered they had a treasure on their hands: It’s the only image of Washington’s tent in use, painted from life by an artist in the field.

The precision of the perspectives and terrain profiles make it as close to a photograph as you’re ever going to see of the Revolutionary War.

“More than a photograph, I like to call it a Google street view of the Revolutionary War,” said Phillip Mead, the museum’s chief historian. “It’s a panorama.”

The painting shows Washington’s encampment at Verplanck’s Point in New York, with about 10,000 soldiers — more people than the average Colonial city of the time. Even at 7 feet long, the painting cannot show a lot of detail of an army that size, but it correctly captured the scope.

Using the panoramic perspective in the paintings, curators can pinpoint exactly where L’Enfant was standing when he painted it. By cross-referencing the painting with maps and documents, they can determine exactly where each state regiment was encamped.

The verification of the painting’s authorship and date changed the attributed date of another painting by L’Enfant of the West Point encampment. Held at the Library of Congress, that work was thought to have been painted in 1778. But, based on evidence in the museum’s painting, it is now believed to have been done in 1782.

In August 1782, Washington had parked both his tent and his army along the Hudson River in order to catch the attention of French. At that moment, the British occupied New York City, peace talks had started in Paris, and Washington needed his army to look its best.

Washington made every solider erect a bower canopy in front of his tent, and ran the troops through military exercises for the benefit of the French. He created a show of strength to convince the French to continue to support the revolution.

“He knew that the British plans might include an escalation of the war again, and he was going to need French help — and he was probably going to need French help to take New York City,” said Mead. “That’s a big request.”

The war was less than year from ending.

After the war, L’Enfant went on to design the layout of Washington, D.C., which to this day retains the street pattern he envisioned. When he died in 1825, he was penniless, a permanent guest of the Digges family estate in Maryland.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.