Requiem for the old reliable school vending machine?

Listen

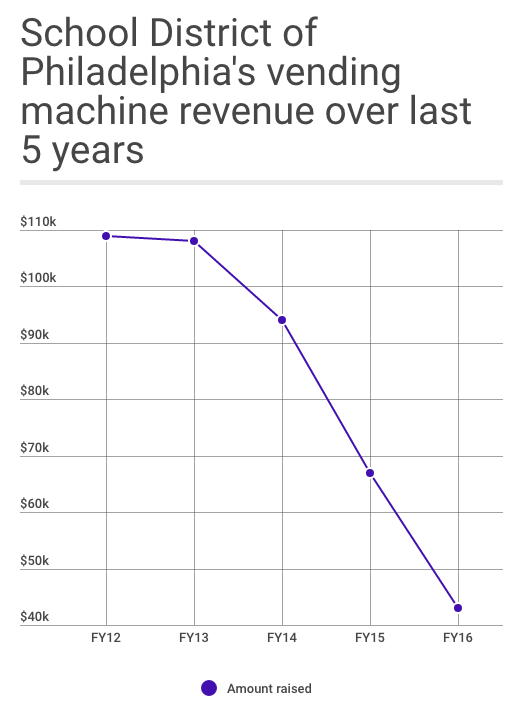

A dramatic dip in vending machine commission suggests that public health advocates may have finally created a school eating environment without junk food loopholes. (Emma Lee for NewsWorks, file)

School vending machines are offering healthier options and are less popular than ever. Is that a good thing?

On those days when another helping of sloppy joe doesn’t seem appetizing or prudent, students have always had an escape: the vending machine.

But in Philadelphia — and around the country — this humble dispenser of snacks and sodas has been bleeding money and popularity. The decline corresponds to regulations — first local and now national — that limit the kinds of junk food schools can stock.

Now this is hardly a fiscal crisis. In Philadelphia and other big cities, snack machines aren’t a major source of revenue.

But the dramatic dip in vending machine commission does suggest that public health advocates may have finally created a school eating environment without junk food loopholes, a rare condition where the only choice is healthy fare.

The decline also raises a question: Is this the end of the road for the once-cherished school vending machine?

A short history

Schools have been selling snacks since at least the beginning of the National School Lunch Program in 1946. By 2005, according to a USDA survey, 98 percent of high schools and 87 percent of middle schools had a vending machine. Meanwhile, 92 percent of secondary schools offered for-purchase snacks during lunch, often called “a la carte” items.

A la carte items and snacks dispensed via vending machines have been dubbed “competitive foods” by researchers because they compete with the traditional school lunch. Back in 2005, they were competing pretty well. That’s partly because there were few restrictions on what schools could sell outside the school meal, which was itself subject to fairly significant regulation.

“If you restrict, say, the kind of options you can sell in the cafeteria, but not in the vending machine that creates an opportunity for the vending machine,” said Joanne Guthrie, a research nutritionist with the food economics divsion of the United States Department of Agricultre (USDA).

Though no official figures date back that far, the School District of Philadelphia says it made over half a million dollars annually in vending machine commissions roughly a decade ago. But the days of robust revenue didn’t last.

“There’s been massive changes in school nutrition in general — both what’s sold in school vending machines as well as school meals in the last decade or so,” said Daniel Taber, vice president of research and evaluation for Healthy Food America and an expert on school food.

Philadelphia led the charge.

In 2004, Philadelphia became one of the first cities to ban soda sales in its schools. The very next year, the district established new guidelines that limited the types of foods that could be sold in vending machines, school stores, and even fundraisers.

By fiscal year 2012, the once-mighty vending machines were generating just $109,000 in commission sales for the district — roughly a fifth of what they had raked in about five years earlier. And the free fall wasn’t over.

In July 2014, federal guidelines went into effect that further restricted the types of competitive foods schools could sell. Under the Smart Snacks Standards, it must be free of trans fats, 200 calories or less, and meet other benchmarks for sugar, sodium, and fat content. This doesn’t mean school snacks have to be super-healthy — certain small bags of chips and even ice cream bars still make the cut — but the days of 20-ounce sodas and massive bags of fried chips have vanished.

So too have revenues. From fiscal year 2012 to fiscal year 2016, vending machine commissions went from $109,000 to $43,000, a 60 percent dip over five school years and a remarkable 90 percent drop over one decade.

Food-services giant Aramark told the district earlier this year that it was terminating its contract to install and supply vending machines for Philadelphia’s public schools. In a School Reform Commission resolution, the district explained the move by saying Aramark had “advised of their decision to exit the school vending market” altogether.

An Aramark representative denied this and said the company will continue vending operations in other school districts.

The district searched for a new vending machine contractor and received just one bid, from a boutique vending machine firm out of Annapolis, Maryland, called Vend Natural. Their product line looks like something out of a Whole Foods market — and would seem anything but natural to the vending machine consumers of just 10 years ago.

Transitional time

None of this is unique to Philadelphia.

The school vending machine industry has been in what Emily Refermat, editor of the trade publication Automatic Merchandiser, dubs a “transition.”

Big companies have been pulling out of school accounts because they’re no longer as profitable, she said. Some smaller firms that offer “turn-key healthy vending” have emerged to fill the void, but it’s an open question whether school vending will ever be as lucrative as it once was.

“I would say in this era of nutritional standards vendors are facing challenges,” said Refermat. “People look to vending machines for snacks. And when snacks they know and they like are not available because they don’t meet the strict nutritional requirements set forth in the guidelines, people go elsewhere.”

The question is, where does those people go? Refermat said she believes many students simply wait until the school hours end or bring their own junk food.

If that’s the case, the drop in vending machine revenue looks like a bad thing. It’s essentially proof that as soon as you try to force-feed healthy snacks to kids, they bail quicker than you can say “Baked Lays.”

Juliana Cohen, a researcher at Merrimack College and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, has another theory.

Earlier this year, she co-authored a study looking at what happened in 11 Massachusetts school districts after that state placed heavy restrictions on competitive foods, restrictions that largely mirrored the national standards that have since followed. Initially, food revenues dropped. But by the second year, all losses associated with competitive foods had been erased by gains in school meal purchases.

In other words, once kids were cut off from vending machine junk they drifted back to school meals, which go by their own set of recently revamped nutritional guidelines. For public health researchers including Cohen, this is good news.

“Now we’re giving them options. But all the options are healthy,” she said. “And we’re finding largely, when they have the choice, now they are choosing healthier school meals.”

What’s more, the uptick in meal purchases was especially prominent among students whose family incomes qualified them for reduced lunch.

Questions remain

Viewed in this context, Philadelphia’s stunning decline in vending machine revenue looks like a win. It’s proof that policy makers have finally created a food ecosystem where kids have to eat healthy.

In the fight against childhood obesity, schools have always been a useful beachhead for public health warriors. It’s the one closed environment where policy makers can largely control what’s served. They can create their preferred food climate.

Cohen also points out that the habits kids pick up in school can influence how they behave elsewhere.

“We know from research it often takes children 12 or more exposures to new food before they start to like it,” she said. “And so this is an opportunity for them to be exposed to these new foods and potentially learn to like these new foods so that we’re in the outside of school they may be requesting those foods, as well.”

A note of caution: These are early returns. And studies like this, while encouraging, don’t get at whether these changes are actually making kids healthier.

“That’s still kind of an open question,” said Taber. “I think schools are really important and the evidence shows that requiring healthier foods in schools can have positive impact on students’ health, but there’s still a lot more to a student’s environment than just what they’re surrounded by in school.”

For now, the results suggest that when students are in school, they’re drifting away from snacks and toward full-meal options. That would suggest officials have finally closed off the little loopholes that can blunt the effectiveness of other nutritional changes.

Now none of that is solace for the good old vending machine. And it makes one wonder: If we’re entering a world where school vending machines have to be healthy, will those machines become obsolete?

Emily Refermat doesn’t think so. In fact, she said, changes in habit caused by new nutritional standards for competitive foods will ultimately save them. Someday in the future, perhaps a high school student will stare at a snack dispenser and wonder not where the cupcakes have gone, but instead savor the prospect of pita chips.

“Part of the answer to keeping school vending will be a new generation of students who grow up with these required items in the vending machine as the only items. They never had access to different items,” said Refermat. “And they don’t know any better.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.