Recounting stories of genocide helps Cambodians find hope

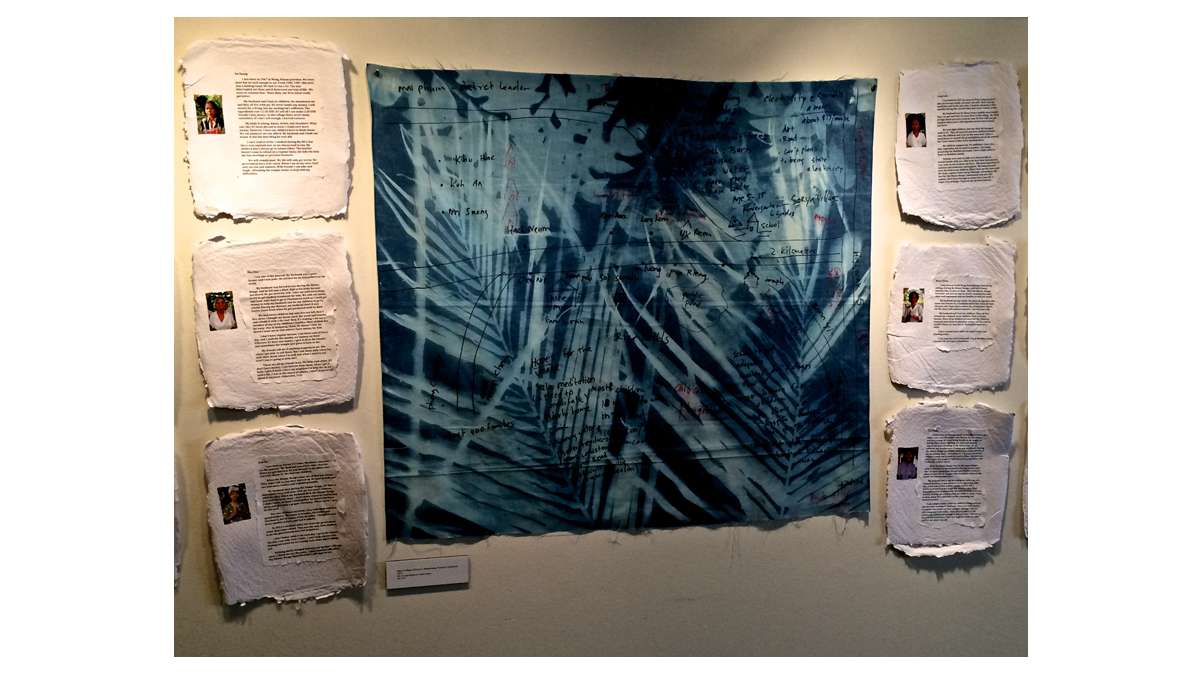

The “map” on the wall is rendered in ink on cyanotype, and amid prints of fronds we see the markings one might doodle on plans for a village. This village is Sorya in Battambang Province, Cambodia, and from this “map” we learn that trash is burned, there’s a latrine and well water (for bathing), rain water (for drinking). The village school serves ages 5-15, K through 6. There’s a market, a gas station and a cremation pyre for the 400 families in residence. A list of dreams includes a place for meditation, a clinic, a home for the elderly, running water, better teachers and a paved road. And “children need playground.”

This artwork is part of “After Genocide: Collected Stories,” on view at Princeton University’s Bernstein Gallery through Oct. 8, with a reception Sept. 20, 4-6 p.m. The exhibit looks at Holocaust survivors’ descendants and survivors of the Khmer Rouge decimation of Cambodia – genocide leaves scars for generations.

Against one wall, with its spine facing the viewer, is what appears to be an old leather bound book titled “Genocide: Where We Come From, Where We Are Going.” There are bookmarks for sections on Armenia, Cambodia, Bosnia, the Holocaust. It’s an altered book by the artist and curator Mary Oestereicher Hamill. “I made it to call attention to the aftermath of genocide, not just those who are killed but the profound repercussions for the survivors and their descendants.”

Hamill, a scholar at Brandeis University’s Women’s Studies Research Center and educator with a PhD in psychology, first went to Vietnam and Cambodia in 2006 with Stanford University students to deliver medical care to remote rural people. “I was there making art, documenting the medical expedition,” says Hamill, who lives in Princeton and New York City. In Cambodia, she was struck by the destitute state of the people. “It was horrific. I wanted to go back to be helpful and learn about their culture.” She had an opportunity to return with Project Hope. “It was striking that Cambodia’s poor were thoroughly neglected. I wanted to make them the focus of an art project to help bring international attention to their situation.”

When she returned to the U.S. Hamill looked for a Cambodian artist with whom she could collaborate. She found Khmer Rouge survivor Chath (pronounced Chat) PierSath, a contemporary artist, poet and humanitarian. Born in Battambang Province, he creates both large and small portraits of people from memory, representing the social and economic disparity among Cambodians. Several volumes of his poetry make up the exhibition.

“His work is outstanding, and he was interested in the same things I was,” says Hamill. Together they collaborated on “Cambodian War Widows’ Project,” presenting artwork by 14 widows in Sorya. Each made a pillowcase memorializing her dead or missing husband by selecting a meaningful object from his life – building tools, barber tools, a T-shirt — and making a print using the photo-based method of cyanotype.

Surrounding the cyanotype map are the widows’ tales. One of the widows is Uy Reen, sister to PierSath. Now 54, she raised four children alone after her husband was killed in 1983. “We were not dirt poor or rich. I can read a little but not write. I only finished one grade of school,” she says in a transcribed narrative. “My father was a Lon Nol soldier; my mother smuggled products from Thailand. With some land for rice plus their incomes, we were ok. But after my father was killed, our lives fell apart. Our family was broken. At the onset of the Khmer Rouge, I was 14. I was hungry at first, but then I was made part of a mobile youth team digging canals.”

Uy Reen is faring better than the other widows. The marriages of these women were arranged. Many lack basic reading and writing skills and relied on their husband as breadwinner. During the Khmer Rouge their property was seized and they were enslaved. They hid in trenches to escape the bombs, and were sometimes tortured and forced to watch the mutilation of others. Some were left with 12 or more children to raise – it is customary to reward parents with many grandchildren. But the children didn’t all survive the labor camps, or if they did, starvation killed them. Few of the women have toilets or more than a crumbling shack, and are often sick and without resources for medical care. To care for grandchildren they must forage for food they can sell. A belief in Buddhism is what keeps them going — there is no government assistance.

The project of pillowcases in cyanotype was selected because “it’s a very simple process that makes use of strong sunlight, in abundance in Cambodia. War widows have hardly any possessions but have memories of their husbands and attachment to particular objects and use the object in creating a memorial to their husband,” says Hamill. “Laying objects on the treated material in sunlight, then rinsing with water, results in a shadow-like interpretation. The pillowcases are allusions to the marriage ceremony bed which, in Khmer culture, has the couple lying down on a pillow with wrists tied with a cord.”

With a day job in agriculture in Lowell, Massachusetts, to supplement his art income, PierSath spends half the year in sister’s house in Sorya, helping the community. PierSath was lucky. With the help of a sponsor he was able to get to Colorado and then California, where he was educated, ultimately earning a master’s degree in community psychology. “He came here with nothing and became an artist, showing internationally,” says Hamill. “He’s very talented, and makes art as a way of expressing his own profound history and concern for other people. He has worked with needy people around the topic of AIDS and combined making art with helping people – that enables him to get stronger. Working together on this project, we found that making art and telling their stories helps people to feel less hopeless. My goal is to raise understanding of their plight.”

____________________________________________________

The Artful Blogger is written by Ilene Dube and offers a look inside the art world of the greater Princeton area. Ilene Dube is an award-winning arts writer and editor, as well as an artist, curator and activist for the arts.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.