Qualified employees increasingly hard to come by in manufacturing sector

ListenOberg Industries’ tucked away buildings in Freeport, Pennsylvania are easy to miss. But inside the nondescript structures are tidy rows of machinery worth hundreds of thousands of dollars each. In one department, refrigerator-sized electric discharge machines, which cut metal using wire, sizzle away like cooking bacon. In another, workers operate manual machines. In one room a worker runs quality assurance using a high-tech instrument.

Oberg Industries’ tucked away buildings in Freeport, Pennsylvania are easy to miss. But inside the nondescript structures are tidy rows of machinery worth hundreds of thousands of dollars each. In one department, refrigerator-sized electric discharge machines, which cut metal using wire, sizzle away like cooking bacon. In another, workers operate manual machines. In one room a worker runs quality assurance using a high-tech instrument.

Oberg makes really precise parts for other companies, in everything from medicine, to defense, energy, and aerospace markets. It has been growing rapidly, but Bryan Powell, who works in human resources, said the company has one major challenge: staffing. That includes machinists and operators of computer controlled machines, as well as other advanced manufacturing workers.

“There’s a small pool and it’s been fished out and all the competitors and us are fishing from that same small pool,” he said.

Some areas – like Harrisburg, Reading, and Scranton-Wilkes-Barre – gained manufacturing jobs over the last year, but the overall trend in the sector has been decidedly downward for many years. And though there are fewer jobs in production, employers like Oberg are having a hard time finding qualified employees. Workforce development organizations like the Three Rivers Workforce Investment Board have made manufacturing a priority, but the lack of skilled employees persists.

A matter of perception

Oberg offers competitive wages, runs a referral program that gives employees up to $1,500 for a referral, and operates an intense apprenticeship program that they say costs the company $250,000 per trainee. They also tap all the major job websites, go to job fairs, and use training centers and workforce development organizations.

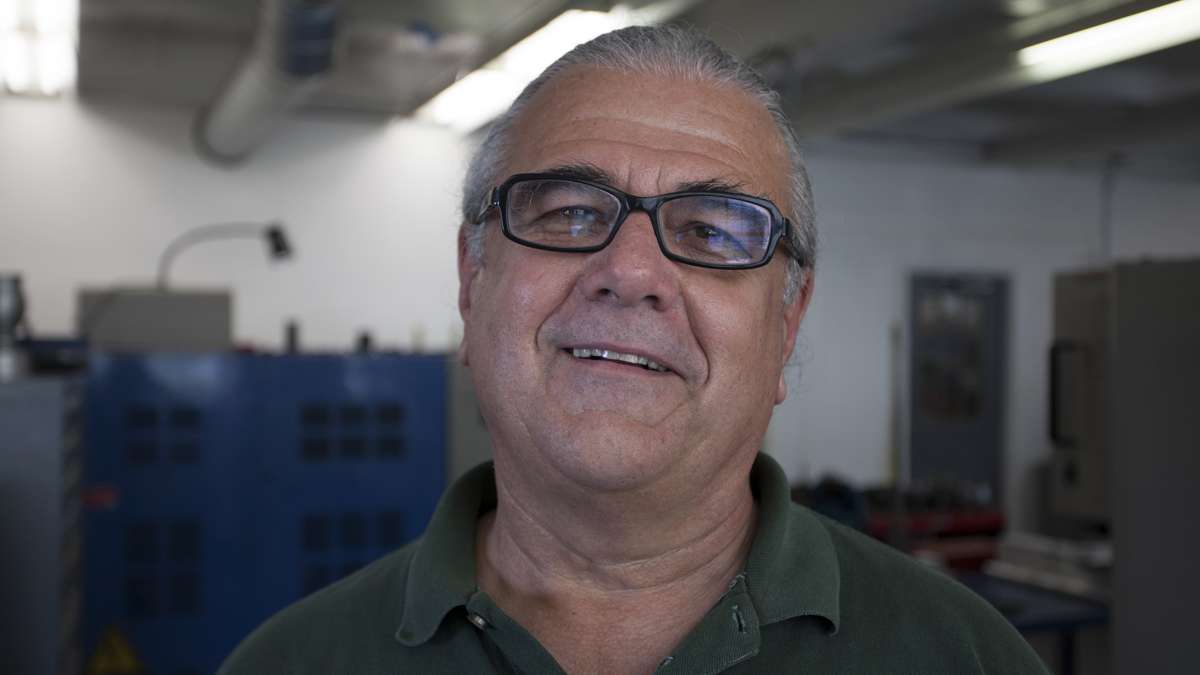

Still, none of that is enough to fill all the positions, and Lou Proviano, Human Resources Director, has the daunting task of finding additional qualified employees. He said last year he spent several hundred thousand dollars on recruitment. “We’ve recruited people out of the Carolinas, Michigan, New York, out west. When you think of headhunters you think for managers and executives doing that, and relocation packages. We’re doing that at the machine and manufacturing levels.”

One reason for that is perhaps the perception around the industry. Chris Boltz is a manufacturing engineer, a third generation Oberg employee who works with the sizzling electric discharge machines. He started there in 1998, after graduating as an honor roll student from high school.

“When my guidance counselor found out that I wasn’t going to be going to college, I was coming here instead, she actually called me down and told me I was throwing my life away and that I needed to go to college and that this was the wrong thing to do,” he said.

Looking toward the future

There are training centers working to fix that perception and to train people for manufacturing jobs. One of them is the University of Pittsburgh’s Manufacturing Assistance Center (MAC).

The MAC instructs students in math, trains them on machines like lathes, mills, and grinders, and then progresses to classroom computer instruction and practice on advanced, computer controlled machines.

Guy Mignogna teaches at the MAC and has 30 years of experience in the industry. He said a whole generation has steered clear of manufacturing jobs, something that’s becoming a problem even with fewer available jobs. “My generation is starting to retire, so a lot of companies are what we call heavily gray, so they’re starting to look for machinists,” he said.

About 75,000 manufacturing jobs in the Pittsburgh metropolitan area are currently held by people over 45. Statewide, 55-percent of all manufacturing jobs are held by people over 45. There are about 8,500 openings annually in production around the state.

In addition, there are signs companies that outsourced their manufacturing to places like China are bringing some of their production back to the U.S. The Boston Consulting Group estimates the increase in domestic production of goods will create between 600,000 and 1.2 million direct factory jobs nationally. According to their analysis, the skills gap in manufacturing could become a significant challenge if nothing is done to train a new generation of workers.

At the MAC, Whitney Cicco is trying to become one of those workers. Cicco has a bachelor’s degree and worked in television before coming there. She’s been putting in long hours studying in the computer lab. “I just never considered how computerized and what all you can do with computers in manufacturing,” she said. “It isn’t all dirt and grease and everything.”

Most of the students at MAC are displaced, many are older workers and about 95-percent of them land jobs in manufacturing. But each class is only six to eight students. According to the Three Rivers Workforce Investment Board, about 5,000 people per year graduate from various manufacturing academic programs in the region, not enough to meet demand. A program starting this fall will help recruit and train more high school students.

Meanwhile, at last check, Oberg was advertising 15 openings.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.