Princeton scientists discover common bacterium’s “sense of touch” [video]

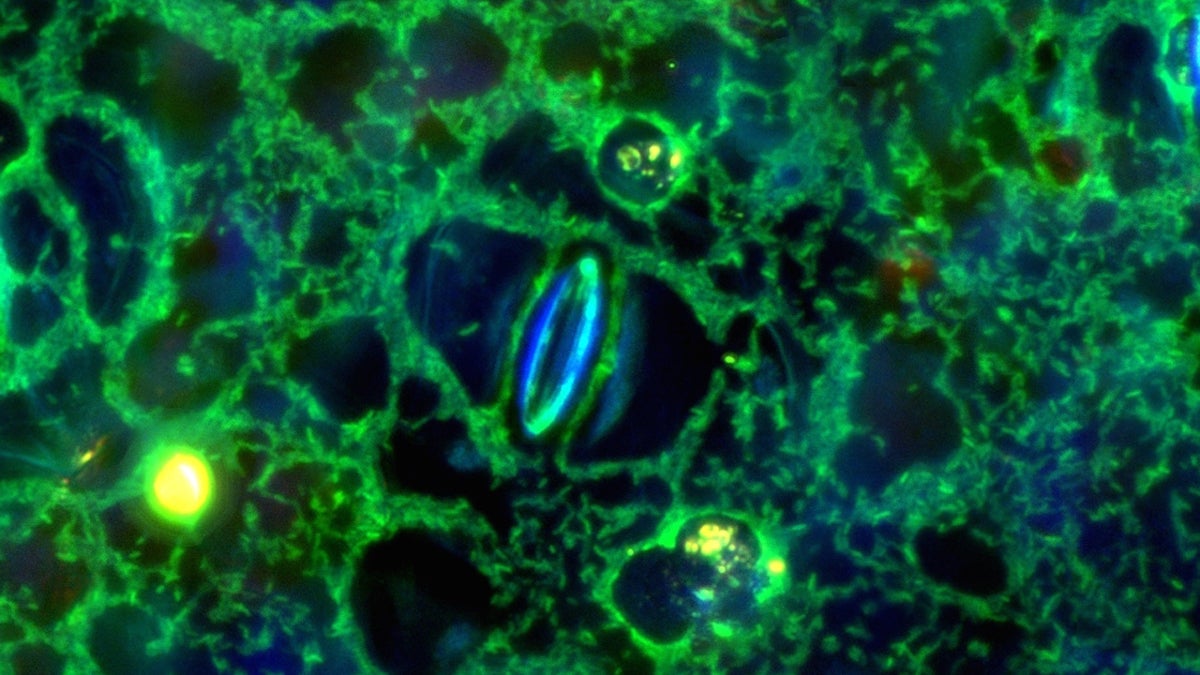

Princeton researchers found that one of the world's most prolific bacteria, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, manages to afflict humans, animals and even plants by way of a mechanism not before seen in any infectious microorganism -- a sense of touch.(Image by Albert Siryaporn, Department of Molecular Biology, Princeton University)

The bacteria Pseudomonas aeruginosa has long puzzled scientists and angered doctors for its ability to infect nearly anything: insects and plants as well as lungs and kidneys. Findings from Princeton University reveal why the species is so prolific and point to a new way of treating infections.

Typically, bacteria only kick into invasion mode if they pick up on chemicals telling them they’re in an ideal environment for growth. Some bacterial species that give rise to urinary tract infections, for example, only do so when they detect a specific human urinary tract signal. This way of “tasting” their surroundings ensures they don’t waste energy turning on extra genes for fighting if they don’t have a reasonable shot at success.

Molecular biologist and lead author Zemer Gitai said to his surprise, however, his team found that Pseudomonas aeruginosa‘s detection system is based on physical touch instead of chemical cues.

“It actually senses the mechanical properties of the host,” he said. “It sits down and feels that there is a rigid thing it’s interacting with and that’s how it knows to become virulent.”

The researchers developed an easier and faster way to evaluate the bacterium’s readiness to kill and saw that it was prepared regardless of the chemical environment.

“All the different materials that we tried — glass, plastic, these kind of gels (something similar to Jello) — all these different things all worked,” said Gitai.

As long as the surface was somewhat stiff and enough bacteria were present, the bacteria began mounting an attack. Gitai said that explains why Pseudomonas isn’t too picky.

“Neither of those conditions is specific to any host,” he said. “You can be on a human cell, plant leaf, or a rock in a stream, and have those same conditions be met.”

The researchers also identified the specific protein on Pseudomonas’s surface that appears to function as its touch sensor. The results, which were published in the journal PNAS, suggest a new way of fighting infections. If scientists can block the bacterium’s ability to feel, it won’t turn on its toxic genes and make people sick, which could help with the growing problem of antibiotic resistance.

The CDC estimates there are 51,000 cases of hospital-acquired Pseudomonas infections every year in the U.S., 13 percent of which are multi-drug resistant.

While Pseudomonas is the first and currently only bacterium known to sense touch, Gitai suspects other species that infect a wide variety of hosts may share the ability. The bacterium responsible for gonorrhea, for example, also has the touch sensor protein on its surface.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.