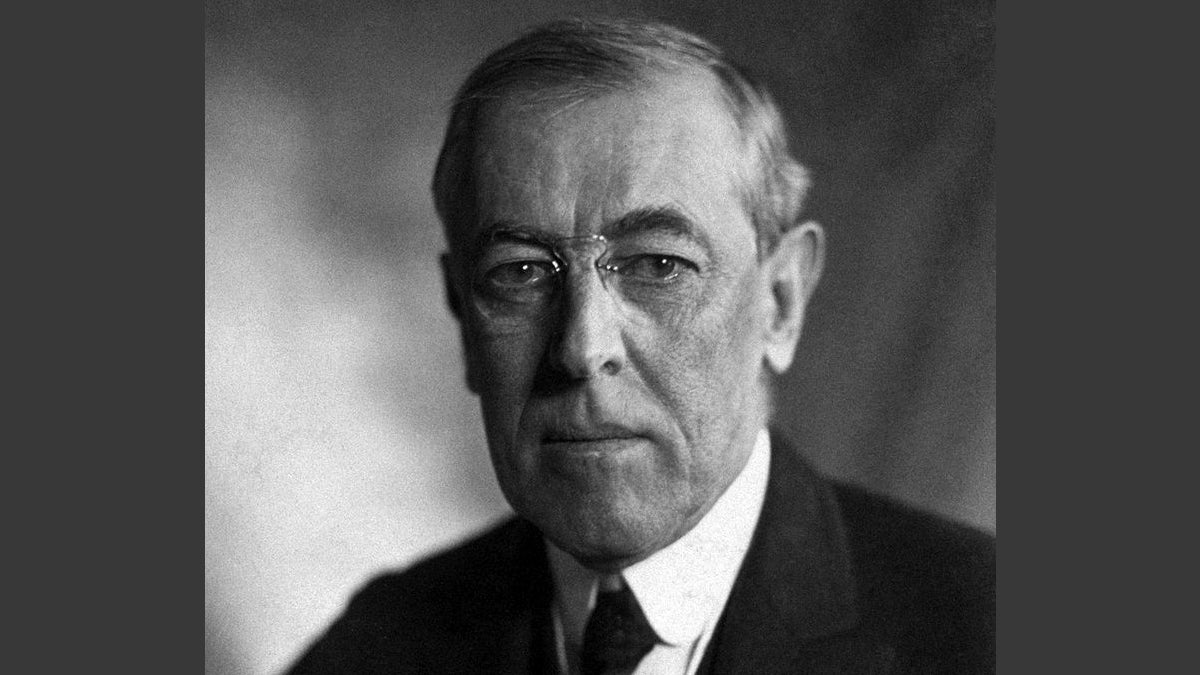

President Woodrow Wilson’s legacy — progressive politics and racism

Listen

So here’s a quick quiz: Who said, “I have to tell you, I hate Woodrow Wilson with everything in me.”

A Princeton student, during last week’s sit-in demanding the removal of Wilson’s name from university buildings? Nope. It was conservative talk-show host Glenn Beck, who routinely rants against the former Princeton and U.S. president.

As Beck correctly emphasizes, Wilson was a key architect of modern American government. But that fact was missing from last week’s protests, which focused only upon Wilson’s miserable record on race.

Nor was there any acknowledgement of the federal government’s historic role in assisting America’s poor and dispossessed, including minorities. As Wilson’s own example reminds us, the government’s commitment to racial equality has been highly uneven. But federal protections and benefits have served as important bulwarks of human dignity and decency in the United States, for all of us. And Woodrow Wilson deserves a good deal of the credit for that.

Wilson came of age during the great industrial boom of the late 19th century, which created enormous disparities of wealth and opportunity across America. While corporate titans amassed huge fortunes, workers toiled in dangerous factories, sweatshops, and mines. In cities, they crammed into filthy tenements; on the countryside, they took refuge in tar-paper shacks. They died from untreated water, putrid meat, and poisonous over-the-counter drugs.

Into the breach stepped a new generation of self-described “Progressive” presidents: Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and Woodrow Wilson. The Progressives insisted that America needed a much larger and more active form of government, to temper the worst aspects of industrial capitalism. As Wilson argued, Thomas Jefferson’s idea that “the government that governs best governs least” no longer fit “the practical politics of America.”

So the Progressives designed a different one. They passed measures to regulate workplaces, food, and drugs. They barred child labor and mandated school attendance. And they won anti-trust laws to break up corporate monopolies. According to Teddy Roosevelt, corporations “should be so supervised and so regulated that they shall act for the interest of the community as a whole.”

But Roosevelt used a light touch in his regulation of corporations, which he called “indispensable instruments of our modern civilization.” By contrast, Wilson pledged to use the newly empowered federal state to break up large companies and restore the economic competition of an earlier age. Defeating TR and Taft in 1912, Wilson immediately cut tariffs on imported goods, which he said benefited big businesses at the expense of consumers. He pushed through the Clayton Antitrust Act, which blocked price-fixing and prevented the same people from sitting on the boards of competing companies. And he instituted the Federal Trade Commission, which investigates unfair business practices.

Wilson also tackled the nation’s banking system, which had left American investors at the mercy of unscrupulous financiers and the unpredictable ups and downs of the economy. His answer was the Federal Reserve, which continues to regulate the national money supply and interest rates in order to cushion us against the worst blows of the business cycle. And he nominated Louis Brandeis—the nation’s leading champion of worker protections—for the Supreme Court.

As the Princeton protesters reminded us, however, Wilson also segregated federal workers in Washington, D.C. At the Paris Peace Conference following World War One, he blocked a Japanese proposal to include racial equality as a founding principle of the League of Nations. And he hosted a private White House screening of the notorious D.W. Griffith film Birth of a Nation, which vilified African-Americans and venerated the Ku Klux Klan.

That’s why blacks like W.E.B. Du Bois—an early supporter of Wilson—broke with him during his presidency. But African-Americans flocked to Wilson’s Democratic Party in the 1930s, when it presided over another great burst of government: Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal.

In some ways, the New Deal echoed the vision of FDR’s distant cousin Teddy Roosevelt: instead of trying to break up large businesses, it would regulate them in the public interest. But it also reflected Wilson’s ideal of a strong national state that would protect workers against the excesses and unforeseen consequences of modern capitalism. Franklin Roosevelt made the federal government into the employer of last resort, putting millions of people to work via the Works Progress Administration and other so-called “alphabet agencies.”

These new agencies discriminated against African-Americans, who were–as per the black adage of the day–the “last hired and the first fired.” But the New Deal also kept many destitute blacks afloat, as W E. B. Du Bois acknowledged. “Any time people are out of work, in poverty, have lost their savings, any kind of a ‘deal’ that helps them is going to be favored,” he wrote. “Large numbers of colored people in the United States would have starved to death if it had not been for the Roosevelt policies.”

By 1936, in his first re-election effort, FDR garnered nearly three-quarters of the black vote. And African-Americans have remained intensely loyal ever since to the Democratic Party, especially after it spearheaded federal civil rights reforms in the 1960s.

To be sure, these years also witnessed the federal wiretapping and harassment of African-American leaders like Martin Luther King, Jr. And some of the key triumphs of the civil rights era—including the Voting Rights Act—are still being contested today.

In balance, though, the federal government has been a force for justice and equality across the last century. That’s especially the case when it comes to African-Americans, who continue to suffer discrimination and poverty in our society. But they also vote in overwhelming percentages for the party of “big government,” the Democrats, because they understand that their circumstances would be many powers worse without federal programs and protections. Public housing, Medicare, occupational safety, mass transportation . . . the list goes on and on. And they’re all legacies of the Progressive doctrines espoused by Woodrow Wilson, who understood that modern Americans needed the assistance of a larger, more supple national state.

That’s also why Glenn Beck despises him. So does the newly elected Speaker of the House, Paul Ryan, who blasted Wilson and his fellow Progressives in a 2010 interview with Beck. “I see Progressivism as the source, the intellectual source for the big government problems that are plaguing us today,” Ryan told Beck. Progressives, Ryan added, “create a culture of dependency on the government, not on oneself.”

And just last week, the conservative Federalist website praised Princeton students for protesting Wilson. “Asking a private school to stop honoring an authoritarian hatemonger who also happened to be one of the most destructive presidents in the history of the United States is about the sanest thing I’ve heard happening on a college campus in a long time,” wrote senior editor David Harsanyi, in a rare right-wing tribute to the recent wave of campus demonstrations.

The Princeton students ended their sit-in after the university agreed to initiate a conversation about retaining Woodrow Wilson’s name on its buildings. That’s exactly as it should be. But I hope the conversation includes a full reckoning with Wilson’s legacy, including his expansion of government regulations and services. His conservative antagonists certainly remember that. It would be a pity if liberals forgot it.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.