Postcard from Tempelhof

Photo: Berliner Morgenpost

Aug. 26

By Arrus Farmer

For PlanPhilly

The future of the Tempelhof Airport in Berlin has been one of the most hotly contested urban development issues facing that city in decades. Like Philadelphians, Berliners are making a stand to have their voices heard on development issues. In a city known for public demonstration, citizens are combining protest, petition and ballot measure to send a clear message to planners and policy makers alike: hands off Tempelhof. And the media is placing this battle in the spotlight.

The last flight takeoff – in October 2008 – was covered on national television: moderators reminisced about the massive building’s history, black and white news reels of 1920s air shows depicted the site in its glory, and teary eyed city residents bade adieu to Berlin’s third airport.

Months later, with complex public ownership issues settled between the city and federal government, planning and implementation for a new mixed use community on the site could proceed, or so it was thought: A new ballot initiative now seeks to extend preservation rules to include the entire airfield, in addition to the already preserved building and runways.

So if the planned future of the “Tempelhof Liberties” joins the ranks of urban visions that never came to fruition, it will not be due to a lack of funding or poor political support. The factor that led to project failure would be an increasingly active and disruptive public initiative to stop redevelopment.

History

The “Tempelhofer Liberties” is a plan that envisions development of the edges of the Tempelhof Airfield into integrated mixed use urban quarters while reusing the historical terminal building for civic programming and preserving the landing strips as the center of a 500+ acre recreational lawn, memorializing the site of the 1948-49 Berlin Airlifts.

Photo: Berlin Senate for Urban Development Division IIB

“Tempelhof Liberties” Vision Plan showing new edge development

The airfield location has been in use for nearly 150 years as a staging point for military and civilian exhibitions, including parades, ceremonies and later air shows. In 1936, the 3 million square foot terminal structure was finished under the watchful eye of Adolf Hitler, and at the time was one of the largest contiguous buildings on earth. Both the landing strips and the terminal building are protected under monument status due to their historic significance.

Much changed over the 70-plus years since the doors opened in central Berlin: the fall of the Third Reich, the Allied occupation of the field, the rise and fall of the Berlin Wall, and the reunification of the German Federal State. One event however never occurred: Tempelhof Airport never reached its projected capacity of more than 6 million flight passengers per year.

By 2008, Tempelhof and the entity that operates it were spending more money to run and maintain the massive structure and its surroundings than they were taking in. Several factors contributed to this slow descent into insolvency: The partitioning of Berlin eventually left the city with three relatively small airports and a population just short of 3.5 million. In 1999, after the fall of the wall and concurrent to the aggregation of government functions in Berlin, planning began for a new international airport on the outskirts of the city that would provide a 21st century gateway for the capital of Europe’s largest economy.

The successful operation of the new Berlin-Brandenburg International Airport (BBI) on the site of the existing Schoenefeld Airport would require the eventual closure and halt of air service at Tegel International and historic Tempelhof. Both Tegel and Tempelhof are urban airports, precluded from today’s Airtropolis model, connected to transit but bound from expansion by the neighborhoods that surround them. (Many airports in Germany prohibit night flights, making them more hospitable neighbors).

Planning in protest

Many objections to Tempelhof’s operational halt came from Berliners who are attached to their neighborhood airports and have benefited from convenient connections to Europe and abroad. In the months approaching its closure commentators and community organizations began weighing in on the issue and In April of 2008 more than 530,000 city residents voted to keep Tempelhof open and operational on a ballot measure that fell just 79,000 yes-votes short of capturing the needed 25 percent majority.

The Airfield was closed in October without a clear vision for future use: no new tenant and no schedule for development and reopening. Meanwhile citizen agitation grew as nothing happened at the fenced off site and many residents believed they had lost this historic icon forever. A lack of economic drivers and an over abundance of bureaucracy set the implementation of the vision months back: citizen action increased.

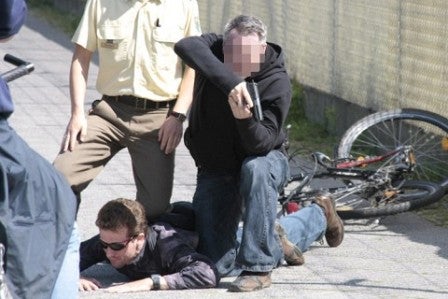

Tension over the future of the site reached its height earlier this summer when demonstrators stepped out to protest the continued prohibition of public access to the airfield. An organized demonstration on June 20th led to the arrest of 102 activists and a seldom seen cover story image of a plainclothes police officer drawing his gun to warn off aggressive demonstrators.

Photo: Die Zeit

Just one month later, 91,000 residents of the Tempelhof-Schoeneberg Borough headed to the ballot box again, this time to extend preservation laws to encompass the entire Airport Complex including all land and outlying buildings, potentially derailing any plans for future development.

While the initiative was successful in getting nearly a 35% quorum, a vote at the Borough level of government has little power to affect the future of the airfield since it is classified as a Capital City Project thus falling under the planning and regulatory jurisdiction of the State of Berlin (Berlin as well as being the Nation’s Capital holds the status of being one of three City-States in Germany).

Planning Democracy: Berlin can look to Philly for inspiration

The German planning process has a strong tradition of and rigid prescription for public participation, especially for highly significant or contested projects. Concepts for these ventures are generally developed through a multi-phase design competition, which includes periods of public presentation.

Public input is encouraged during the various stages of selection and design principles are developed through early and ongoing civic engagement. This system is generally successful and encourages an active interest in urban projects and the built environment. The situation in Berlin concerning Tempelhof Airport, however, is quite reflective of the jurisdictional complications which are common on this side of the Atlantic.

Decision making that ignores local interests and voice both alienates stakeholders and destroys public confidence in the system. We can look at Harrisburg’s push for casinos in Philadelphia’s riverwards of an example. Some will also recall a failed struggle to halt the demolition of the historic Philadelphia Life Insurance Company (PLICO) Building when the Pennsylvania Convention Center Authority side stepped Preservation Alliance efforts reach a compromise in the North Broad Street Expansion.

Photo: Berlin Senate for Urban Development Division IIB – Image from the

“Tempelhof Liberties” Vision Plan

If Berliners doubt the power of the public voice they have only to look to Philadelphia’s Civic Planning efforts on the Central Delaware Riverfront, Pier 11, and the recent reevaluation of the South Street Bridge reconstruction, which brought the public and governance sectors together to produced designs that represent vast improvements over the original concept.

Whether Tempelhof goes the way of the PLICO Building or turns into a process more like the one that created a new South Street Bridge there are clear takeaways from both outcomes.

Public input is best done often and throughout the planning process. More civic engagement and more voices produce development that is more robust, legitimate and better reflects the interests of stakeholders. When planners, citizens and the media collaborate, the result is a more enjoyable, longer lasting built environment.

Arrus Farmer was most recently a Robert Bosch Fellow based in Berlin, Germany working in the planning and administration of large scale public-private developments. He holds both a Masters of City Planning and a Masters of Government Administration from the University of Pennsylvania which were completed earlier this year. Farmer has worked with Praxis on a number of civic engagement projects including the Civic Vision for the Central Delaware Riverfront.

Previous postcards: Detroit Part 1, Austin, China, San Francisco, Germany, Pittsburgh, New Orleans, New York City, Boston, San Antonio, Minneapolis, Detroit Part 2

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.