Police re-examine Reading woman’s death after suicide ruling questioned

Ask those who loved Rebecca Weller most, and they have a story about her ex attacking her.

Morris “Rico” McQuay came so close to killing her so often, they say, that the retelling has taken on a matter-of-fact tone, the horrors heralded with a casual: “Remember that time …”

“One time, he was driving next to us, and Mommy got so scared she made us hide on the floor (of the car) and pulled over ’til he drove away,” said 8-year-old Rishayla, one of five children Becca, 36, of Reading, had with him. “He attacked her in the car another time — he got so mad he punched out our radio.”

“He messed up a few of our cars,” her sister MaLienda, 9, added.

Peggy Weller, Becca’s mother, still has a hole in her wall from her daughter’s head.

“The one time he was choking her, he was choking her with her feet off the ground, banging her head against the wall. That’s a hole I still have in my wall. I saved it,” said Weller, whose mother witnessed the incident.

Everyone begged her to be done with him, worried the violence would eventually turn lethal. Sometimes, she saw their point, if the two protection orders she filed in 2007 and 2010 against him prove anything. More often, though, she returned to him, no matter how much he hurt her.

“I used to tell her all the time this was going to end badly. She once told me: ‘I’m afraid to leave him,’ ” her mother said. “But even when he would leave, she would pursue him. She was not willing to separate from him permanently. It was a sick, destructive love.”

“She went through s— with that guy,” Becca’s best friend, Kericha Pabon, agreed of the couple’s on-and-off relationship that lasted more than 15 years. “I told her all the time, ‘He’s going to be the death of you.’ ”

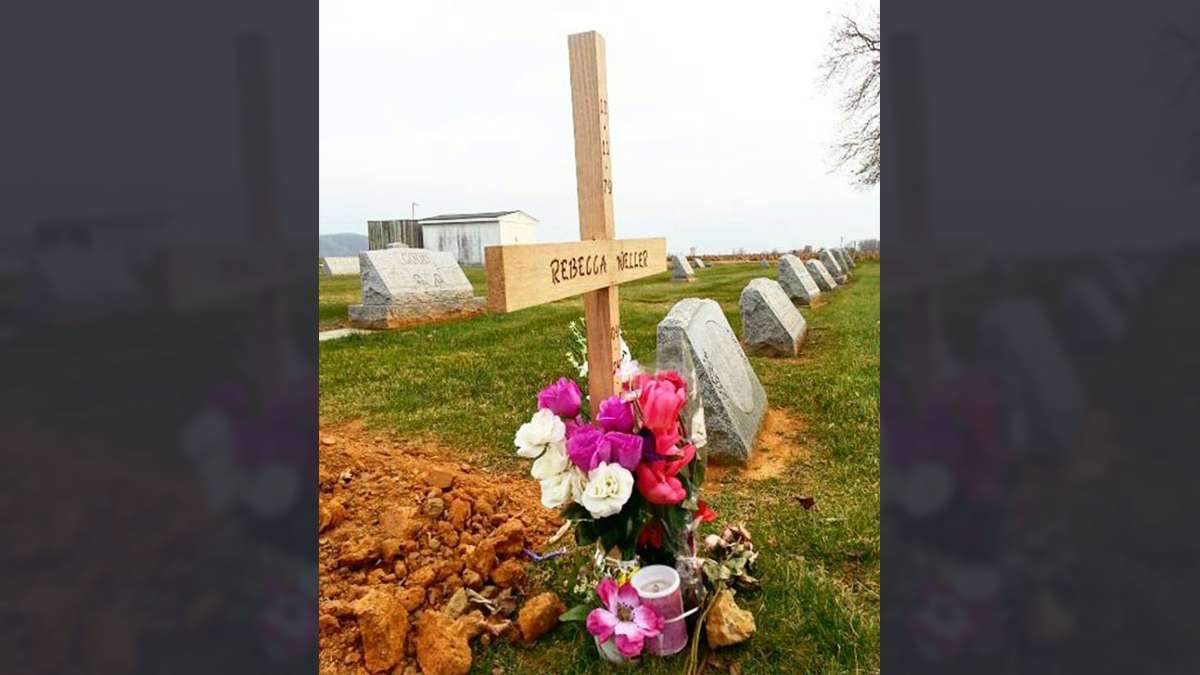

Becca died on a sunny Saturday in September.

She had been shot in the head with the same 9 mm gun she’d bought to protect herself against her abusive ex, police and her family later said. McQuay was there, had been the one to summon police to the car parked curbside on a West Philadelphia block where Becca’s blood painted the driver’s seat red.

But Becca, he told police, had killed herself, becoming so distraught during an argument with him that she turned her gun on herself.

“I never believed that,” Pabon said. “Right off the bat, I knew it was him. There was no doubt in my mind it was anybody else.”

Authorities didn’t agree. On an incident report written the same day, an officer characterized her injury as “what appears to be a self-inflicted GSW [gunshot wound] to the head.” Eleven days later, the Medical Examiner’s Office ruled her death a suicide. Becca’s family and friends said no one in the Police Department or the Medical Examiner’s Office had interviewed them.

Adding to her family’s heartache, police gave Becca’s belongings — including the car, which was registered to Pabon — to McQuay, wrongly believing he was her next of kin. Without the keys, Pabon couldn’t retrieve the car. It sat on the street where the shooting happened for weeks afterward, a morbid attraction for passers-by gawking at the bullet hole in the window and blood-blackened interior. The car even briefly got lost, after a city tow truck relocated it to a nearby street to clear the block for a politician’s event.

Within days of her Sept. 24 death, Becca’s family took to social media to lament such lapses and demand a deeper investigation — and “Justice for Becca.” They’ve held memorials and fundraisers and ping-ponged between Reading and Philadelphia, a 125-mile round trip, doing the detective work they say Philadelphia police and pathologists failed to do. In October, one of Becca’s friends filed an Internal Affairs complaint against the detective who initially investigated the death and a supervisor, claiming they “botched” the case and urging officials to reopen it.

Now, almost three months after her death, homicide detectives have taken over the investigation at the Philadelphia District Attorney Office’s request. Homicide Sgt. Bob Kuhlmeier wouldn’t go so far as to call McQuay a suspect. But he confirmed Becca’s loved ones alerted authorities to enough details that “just didn’t add up” that detectives took McQuay in for questioning.

“Some things came up that seemed unusual,” said Kuhlmeier, adding that detectives now are awaiting cellphone records. “There was enough concern that we said, ‘OK, we’ll pick it up and go talk to people.’ ”

The Police Advisory Commission, a civilian-run police oversight board, also has concerns about the case. Kelvyn Anderson, who heads the commission, has asked homicide investigators to share their findings with him.

Assistant District Attorney Jennifer Selber, who heads the homicide unit at the DA’s Office, declined to comment through an office spokesman because the investigation remains open.

McQuay and a female supporter refused to comment when a WHYY reporter approached him Thursday at the Criminal Justice Center, where he beat an unrelated domestic assault case because the two victims repeatedly failed to appear.

As he walked away outside court, though, he called over his shoulder: “I’m not a murderer. That’s all I’m gonna say.”

His parents have declined to comment, although Weller said they told her McQuay has been despondent about Becca’s death.

Weller doesn’t know what to think, grasping at each new bit of information in hopes that it will bring closure and either confirm the suicide ruling or prove a homicide. The uncertainty, she said, is agony.

Whatever authorities decide, she hopes the renewed attention on her daughter’s death will spare others the torment Becca’s loved ones have endured.

“Really what I want to come out of this situation is that this would never happen again, that they will never have a known abuser standing by a dead girl, and they won’t even take him to the station, they will just take his word as the final authority, and give him the dead girl’s things,” Weller said, sobbing. “Now, it’s unlikely anyone will ever be able to prove what happened there, because so much evidence was destroyed or not collected.”

Big plans gone awry

She should have never been there.

Becca had big plans for the day she died, her family said: A morning spent watching her son and daughter play on a Reading community youth football team, a midday bash at Chuck E. Cheese to celebrate her baby’s 5th birthday, and a road trip that night to South Carolina, where she planned to move with her children as a fresh start away from McQuay and the gritty streets of Reading.

Instead, as the day dawned, McQuay, 36, insisted she drive him to Philadelphia, where he was staying with a girlfriend.

Her children begged her to stay home.

“I said: ‘Mommy, don’t go; he’s going to hurt you,’ ” Rishayla said. “She said: ‘I have to. He’s a little upset.’ ”

With a promise that she’d return in time for the football game, Becca left.

Her oldest, Rishonna, then 14, called her an hour later to check on her.

“Shonnie said [Becca] was hysterical, frightened, couldn’t breathe,” Weller said. “She could hear [her father] screaming at Becca, but Shonnie couldn’t make out what he was screaming. She could hear the engine racing, and she was telling her mother to get out of the car, but [Becca] said: ‘I can’t.’ She told Shonnie: ‘I’ll talk to you when I get home.’ ”

But that was the last time Rishonna ever talked to her mother. Becca never made it home.

Rishonna continued calling and texting both parents, growing increasingly worried. Neither responded.

Just after noon, Weller’s phone rang. It was McQuay.

“She’s dead,” he told her. “We were arguing, and she lost it, and she shot herself.”

That appeared to be true to the first investigators on the scene.

Beyond McQuay’s account, they relied on a few key facts to decide the case was a suicide, said Lt. John Walker of Southwest Detectives, which handled the initial investigation. Becca’s hand was “locked” on the gun in a way no one could have staged, and the stippling of gunshot powder on her head suggested a suicide, Walker said.

Further, a witness backed up McQuay’s account of what happened, said Walker, who wouldn’t discuss who the witness was nor what she saw.

Fred Alston, who owns a vehicle tag agency along the stretch where the shooting occurred, told WHYY that one of his customers had parked behind the black Cadillac sedan where Becca and McQuay argued. The woman watched the drama unfold as she waited for Alston to open for business.

“She said a man and woman were sitting in the car, the man got out of the car, and then she shot herself,” Alston said. “She was really upset, because she never saw anything like that before.”

Investigators told Becca’s family a witness described the shooting as a suicide.

They remained unconvinced, saying Becca’s car had dark tinted windows, obscuring the view inside. Everything happened within seconds, they add, so the timing demands close scrutiny.

“The reality is nobody wants to believe anybody they loved committed suicide,” Walker said. “It’s a tough thing for anyone to understand, especially if someone has children, and especially in this case — it was her daughter’s birthday that day.”

He added: “But we have to go by physical evidence. The physical evidence was clear in this case. There’s absolutely no way somebody could have shot her.”

Walker acknowledged investigators didn’t immediately know about the couple’s violent history — but insisted it didn’t make McQuay a murderer.

“This is a sad story of a relationship that clearly was tumultuous throughout,” Walker said. “The friends are always going to blame him for anything that happened. But he didn’t pull that trigger. He was there. Could he have caused her to pull the trigger out of desperation, out of frustration, to make a spontaneous decision based on the situation she was in at that second? I don’t know.”

But that’s not homicide, he added.

An expert weighs in

Becca’s family says they’ve collected plenty of “evidence” themselves that makes a suicide ruling questionable.

That includes everything from the lack of blood spatter in the car, to the way the bullet shattered the car window, to the mysterious, bloodied black tank top tied inexplicably to the driver’s side seatbelt. Becca’s wallet — with money she’d saved up to fund the family’s move — remains missing, they say, possibly a motive to murder. And in the car, her loved ones found bakery-made birthday cupcakes for her daughter and new clothes she bought — proof, they say, that she had no plans to die.

Generally, cops hate when people play armchair detective. With the popularity of true-crime shows and books, sleuthing civilians can become meddlers who create headaches for real-life detectives, who say thorough investigations take time and specific skills.

But Becca’s family complains that Philadelphia detectives didn’t take the time to ensure justice in this case.

And Vernon J. Geberth thinks they could be right.

Geberth wrote the book on death investigations.

Literally. Actually, a few books.

A retired commander in the New York City Police Department, Geberth said he has participated in, supervised, or consulted on more than 8,000 death investigations. His “Practical Homicide Investigation: Tactics, Procedures and Forensic Techniques” — first printed in 1983 and now in its fifth edition — is used in many police academies, as well as the FBI Academy.

He declined to comment specifically on Becca’s death, saying he doesn’t know all the details and nuances of the investigation.

Still, he said, detectives so often jump to the wrong conclusion during death investigations that he wrote a position paper in 2013 titled, “The Seven Major Mistakes in Suicide Investigation.”

When cops peg a death as a suicide, he said, they often take shortcuts that could hide clues pointing elsewhere.

“Investigatively speaking, all death investigations should be handled as a homicide investigation until proven otherwise,” Geberth said.

That means investigators should have interviewed Becca’s family and probed her background, swabbed her and McQuay’s hands for gunpowder residue, and towed the car for fingerprinting and thorough crime-scene processing, Geberth said.

Past abusive behavior can predict future lethal behavior, making lethality indicators worth exploring, he added.

In a 2007 application for a protection order, Becca chillingly wrote: “He always threatens to kill me if I date anyone else, and that he’ll kill them, too. He was arrested for banging down my door with a butcher knife. He’s put my head through the bathroom wall. He choked me numerous times until I passed out. He put a screwdriver in my throat and threatened to kill me. He’s put a gun to my head, in my face and in my mouth too many times to count.”

McQuay also has been arrested at least three times for violent offenses, and at least one involved Becca, court records show. In May 2005, police arrested him after he allegedly grabbed Becca by the hair, threw her to the floor, choked her and slashed her car tire after she refused to drive him somewhere, according to records. When police responded, he allegedly ran away, punching one officer in the face before they could subdue him, an affidavit states. He pled guilty to aggravated and simple assault and got sentenced to six to 23 months in prison, records show.

In his most recent case, McQuay allegedly punched an ex-girlfriend and repeatedly kicked and tried to punch her male friend Oct. 28 in Grays Ferry, court records show. He was scheduled for trial Thursday on charges of simple assault and terroristic threats, but both victims failed to appear, so prosecutors withdrew charges for one victim and the judge dismissed them for another.

In cities where body counts can climb quite high, shortcuts can result when police feel overburdened, Geberth said. A Philadelphia police spokeswoman said the department doesn’t specifically track the total number of death investigations they do annually, but 3,130 people died last year and so far through Dec. 4 of this year in accidents (2,216), homicides (581), and suicides (333), Health Department spokesman Jeff Moran said. Most of those deaths would involve police investigation.

Investigative oversights early on can make it tougher for homicide detectives to build strong cases and easier for defense attorneys to instill doubt in judges and juries, Geberth said.

“Do it right the first time. You only get one chance,” he said, reciting a mantra he often repeats in his writings and seminars. “A premature classification of suicide can taint the entire investigation.”

Walker defended his detectives’ methods, saying they processed the car on the scene and didn’t tow it because they were done with it. He was sorry for the confusion over Becca’s next of kin, he said, and the delay it created in returning her belongings to her mother and children.

Walker remains confident the suicide ruling will stand.

Homicide investigators say the case remains a priority for them.

‘Don’t cry for me’

In a way, it doesn’t matter what authorities ultimately decide.

Her children, long weary of the abuse they watched their mother endure, have already decided their father’s guilt. They’ve asked their grandmother to help them legally remove his surname from theirs. And they don’t want to see him again.

“When Jamir and I were standing in front of the casket, he said to me: ‘My daddy did this, my daddy put her there, my daddy did this’ over and over again,” Weller said of her 12-year-old grandson. “I told him, ‘Jamir, the police say this was a suicide.’ And he just said, ‘Nanny, don’t ever say that to me again.’ They all believe he killed her. Nothing that any legal system says will ever change their mind.”

Now orphans, the children remain rootless, staying sometimes with one of Becca’s friends and sometimes with their grandmother. McQuay paid Becca no child support, so she often juggled two jobs to support them, her family and friends said. One of Becca’s friends has set up an online fundraiser to support the children now.

Peggy Weller, a nurse at Wernersville State Hospital in Berks County, had planned to seek full custody. Instead, she’ll cede their upbringing to McQuay’s parents. That might seem surprising, given Becca’s turbulent history with McQuay. But Weller explained that Becca had a great relationship with McQuay’s parents, who she said dote on the children and will be better able to provide for them. Berks County Family Court ultimately will decide the children’s fate.

With closure elusive as the investigation winds on, Weller finds comfort now in her Mennonite faith.

“I personally believe that Becca is seated at the seat of Our Father in a more glorious place than we will ever know until we’re there,” Weller said. “My sister said Becca came to her [as an apparition after her death] and gave her a hug — a real hug, like she could feel it. She told her: ‘Don’t cry for me. I am all right.’ That gave me such comfort, like you couldn’t even imagine.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.