Philly’s got history, playing host to political conventions 1776-2016

ListenPhiladelphia has hosted national political conventions from the time of the Revolution to the modern era.

From the Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia:

The Pennsylvania State House, later known as Independence Hall, was the site of both the signing of the Declaration of Independence in 1776 and the Constitutional Convention in 1787. In the mid-nineteenth century, as national party conventions became the norm, politicians often returned to Philadelphia to nominate candidates in the city most closely associated with the nation’s founding ideals. Between 1848 and 2012, nearly one of every four major national political party conventions was held in Philadelphia, drawing visitors to the city and reinforcing the city’s place as an important center of national politics.

In June 1848, thousands of Whigs (although only three hundred delegates) convened in Philadelphia to settle the contested presidential nomination of their party in a city convenient to the still-underdeveloped national capital of Washington, D.C., and accessible by rail from New York City and from the South. The contest for the nomination was between the Northern anti-slavery “Conscience Whigs,” who supported perennial presidential candidate and Whig leader Henry Clay, and the Southern “Cotton Whigs,” who supported General Zachary Taylor, a hero of the Mexican-American War. The convention met at Ninth and Sansom Streets in the lower saloon of the Philadelphia Museum Building, also called the Chinese Museum. The convention nominated Taylor on the fourth ballot, and in the general election Taylor carried Philadelphia by more than 10,000 votes. The convention adopted no platform, but Whigs stood for a protective tariff (high tax on imported goods), a national bank, and internal infrastructure improvements such as roads, canals, and railroads.

Philadelphia hosted two conventions in 1856, first the American or “Know-Nothing” Party and then the first national nominating convention of the new Republican Party. The anti-immigrant Know-Nothings were so called because of their origins as a secret society whose members denied knowledge of their party when asked. Their Philadelphia convention, attended by fewer than 200 delegates, nominated former president Millard Fillmore of Buffalo, New York, and adopted a platform that called for a twenty-one-year waiting period for immigrant naturalization, preference for native-born citizens in public office, and prohibition of convicted criminals from entering the United States. On slavery, the convention called for popular sovereignty in the territories, which caused anti-slavery delegates to quit the convention, weakening the impact of the party.

The newly formed Republican Party met at the Musical Fund Hall at 808 Locust Street. For a party committed to combatting the evil of slavery, Philadelphia offered symbolic resonance as the birthplace of liberty. Many Philadelphia residents, however, were wary of what they perceived as anti-slavery radicalism of the new party. Nevertheless, more than 600 delegates nominated Senator John C. Fremont of California, also known as “The Pathfinder” because of his pioneering expeditions in the frontier West to map the Oregon Trail and his exploits in the Mexican-American War, on the eleventh ballot. The party platform endorsed the admission of Kansas as a state that prohibited slavery as well as massive “internal improvements” in the form of river and harbor expansion and construction and federal funding of a transcontinental railroad.

1872: Republicans Again Nominate Grant

In 1872, Republicans returned to Philadelphia with 800 delegates and nominated the incumbent President Ulysses S. Grant for a second term. They met in the Academy of Music, which had replaced the Musical Fund Hall as the largest musical and convention venue in the city. Their platform endorsed Grant’s Reconstruction policy in the South, the Homestead Act to encourage western settlement, and more tariffs to both raise revenue and protect domestic trade for American businesses. Republicans also called for an extension of women’s rights and equal rights for all races, in keeping with their roots as an anti-slavery party.

When Republicans returned to Philadelphia again in 1900, the party sent more than nine hundred delegates to nominate incumbent President William McKinley, whom they credited with improving business conditions throughout the country. Delegates and visitors to the convention streamed into the city to pay tribute to both McKinley’s Republican party and the city’s history, and in the case of a large celebration at the Academy of Music, site of the 1872 convention, to do both. Large parades made their way down Broad Street on the Saturday before the convention, and thousands visited tourist attractions such as Wanamaker’s department store. A brand new, white-marble Exposition Auditorium (so named to host the National Export Exposition of 1899) had been dedicated by McKinley himself in 1897, and the extremely large convention hall near Thirty-Fourth and Spruce Streets served as the perfect backdrop for the a triumphant Republican party to hold its quadrennial gala. The only rival for McKinley’s popularity was New York Governor Theodore Roosevelt, the Rough Rider of San Juan Hill, who accepted the nomination for the vice presidency even though he had said he would do so “under no circumstances.”

Democrats met in Philadelphia for the first time in 1936, at the newly-christened Municipal Auditorium and Convention Hall, built in 1931 adjacent to the old Exposition Auditorium, now renamed the Commercial Museum. Philadelphia city leaders had raised more than $200,000 and also suspended blue laws against drinking on Sundays in order to woo the party to the city. The Democratic convention of more than 1,000 delegates largely endorsed continuing President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal and its aggressive government spending to combat the Great Depression. No floor votes were counted, only voice votes, and the president was renominated by acclamation. The two-thirds supermajority rule for nominating candidates and passing floor resolutions, which made the party disproportionately beholden to Southern white interests, was formally abandoned at the behind-the-scenes urging of Roosevelt, who understood it appropriately as a Southern veto on Democratic Party actions. This was only one of several traditions Roosevelt broke during presidential conventions, including accepting the nomination in person in both 1932 and 1936. At the University of Pennsylvania’s Franklin Field, Roosevelt spoke to a crowd of perhaps 100,000 people in accepting his renomination, proclaiming in his nomination acceptance speech to a Depression-weary United States that Americans had “a rendezvous with destiny.” The party’s platform, a brief one, largely accepted and advocated more New Deal policies.

Four years later, in 1940, more than 1,000 Republicans met in Philadelphia once again, this time at the Municipal Auditorium and Convention Hall. Republicans nominated businessman and vocal New Deal opponent Wendell Wilkie of Indiana for president on the sixth nominating ballot to oppose Roosevelt. They endorsed a platform that opted not to oppose involvement in the ongoing World War II, but not to advocate for intervention, either. The party also did not argue against the concept of relief for the poor during the Great Depression, but called for state administration of those programs. The Republican convention of more than 2,000 delegates and alternates very generally opposed government spending and called for cuts. In fact, the convention utilized the friendliness of Philadelphia as a city home to both a Republican mayor and Republican governor to convene an “American-Patriotism Session” at Independence Hall to demonstrate how the New Deal was spoiling the freedoms and rights the founders intended.

1948: Three Conventions in One Summer

The summer of 1948, the first presidential election year after the end of the Second World War, was truly the summer of national political party conventions in Philadelphia. Following $600,000 in renovations, the Municipal Auditorium and Convention Hall hosted conventions of three parties: Republicans, Democrats, and the new Progressive Party. Republicans and their 1,100 delegates met June 21-25 and nominated New York Governor Thomas E. Dewey, theit 1944 nominee, on the third ballot, to oppose incumbent Democratic President Harry S. Truman. Republicans stressed an internationalist foreign policy. The party’s central substantive plank (and disagreement with Democrats) was an endorsement of the anti-labor Taft-Hartley Act, passed over Truman’s veto by a Republican-dominated Congress. The Republican platform also called for the repeal of poll taxes and segregation in the South and favored a federal anti-lynching law, which Roosevelt and his successor Harry Truman had failed to pass through Congress, as well as a law prohibiting employment discrimination on the basis of sex.

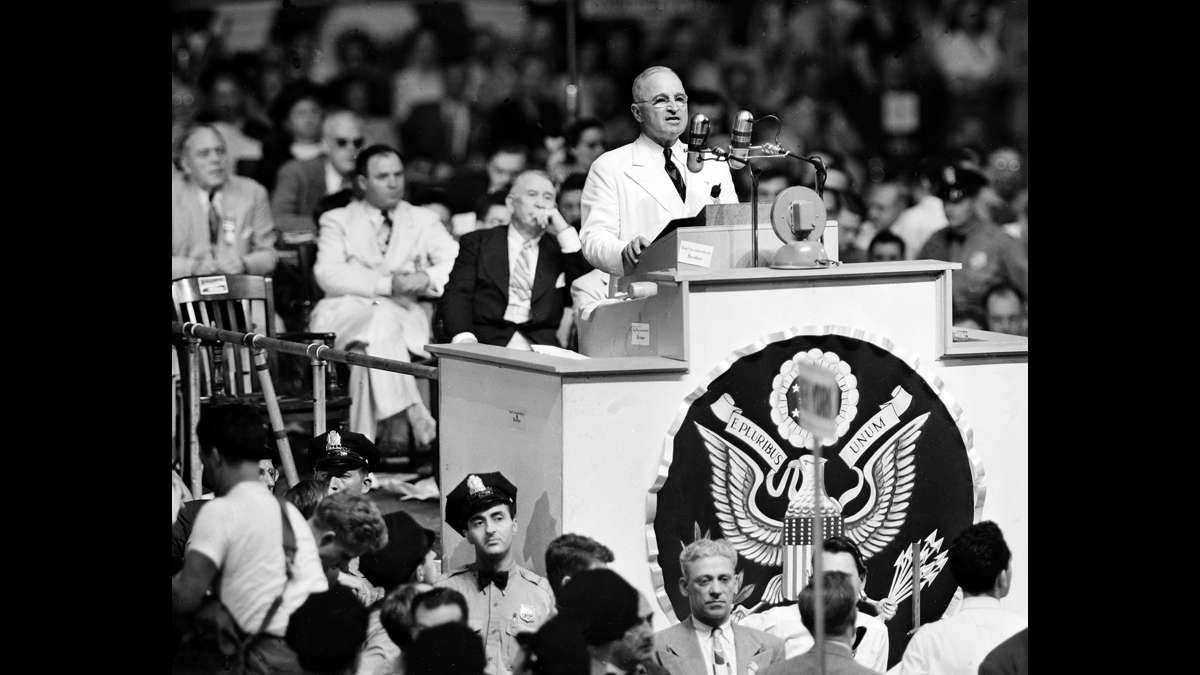

A major Southern revolt rocked the Democratic Party when 1,200 delegates gathered July 12-15 to nominate Truman at the Municipal Auditorium and Convention Hall. Southerners initially supported their own candidate, Senator Richard Russell of Georgia, until Truman soundly defeated all challengers on the first ballot. When Minneapolis Mayor Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota made a floor speech endorsing the first-ever civil rights plank in the party’s platform, Southern delegates walked out of the convention and later formed the “States Rights Democratic Party,” more popularly known as the Dixiecrats. The Democrats in Philadelphia called for repealing the Taft-Hartley Act (a structural impediment to labor union growth), extending Social Security, raising the minimum wage, and establishing a national health insurance program. The temperature in the convention reached more than 100 degrees as delegates attempted to get the business done of passing rules, nominating candidates, and approving the platform. To celebrate convention-goers, Philadelphia’s police and fire department bands paraded down Broad Street to sing and play music for them at the Ritz-Carlton Hotel. The party endorsed Truman’s foreign policies, calling for expansion of the United Nations and diplomacy to handle the new atomic bomb threat. Truman accepted the nomination before a crowd of 16,000 at the auditorium.

The Progressive Party of more than 3,000 delegates met July 23-25 and nominated for the presidency former Vice President Henry Wallace, who made his acceptance speech to a crowd of more than 32,000 spectators at Shibe Park, home to the Philadelphia Athletics baseball team. The party’s platform denounced the U.S.-led rebuilding of Europe known as the Marshall Plan and favored national health insurance, an end to the military draft, an agricultural policy that favored small farmers, and a rethinking of the concept of national sovereignty worldwide. The Progressives also endorsed equal rights for women and racial minorities, as both major parties had.

2000: George W. Bush Nominated

Fifty-two years passed before a major party held another national convention in Philadelphia as the Republican Party attempted to alternate between major cities in the Midwest, West, and South and the Democrats held the majority of their conventions in New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago. On July 31, 2000, more than 2,000 Republican delegates unanimously nominated Texas Governor George W. Bush as their presidential candidate. Unlike earlier Philadelphia conventions, the nomination was a foregone conclusion. What was not was how the party would deal with internal dissent on the issue of abortion and reform of the schedule for primaries. The party avoided a floor fight on abortion and settled the primary calendar without radical changes that would have disadvantaged existing early-nominating states such as Iowa and New Hampshire. Former President Gerald Ford, also in attendance, was taken to the hospital–at first suffering from an earache, for which he was treated and released, but he was later readmitted and diagnosed with a minor stroke. He remained at Hahnemann University Hospital for several weeks after the convention.

The city spent $66 million putting on the weeklong extravaganza, which also was marked by dissent by labor unions that demonstrated in support of striking municipal workers and other groups that organized protests to call attention to social causes. Almost four hundred protesters were arrested during convention week in early August. One event, decidedly not a protest, was “The Best Little Warehouse in Philadelphia” a party organized by U.S. Rep. John Boehner of Ohio. The cocktail mixer and dance party for delegates, industry lobbyists, and their families took place at a secret location in Fishtown.

Union and business leaders united in their enthusiasm for luring the Democratic National Convention back to Philadelphia in 2016, in keeping with the tradition as one of the most politically prominent cities in the history of the United States. On February 12, 2015, the Democratic National Committee announced Philadelphia’s selection as site of the party’s next convention over competing bids from Columbus, Ohio, and a New York City site in Brooklyn. The competition for the 2016 convention and the strength of Democratic allies in the labor movement signaled that Philadelphia continued to be a wellspring of American political activity, laying claim to a heritage as host to more national political party conventions than any other city in the United States. The Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, both drafted and adopted in Philadelphia, were only the beginning of Philadelphia’s role as a battleground of American politics.

Daniel T. Kirsch completed his doctoral degree at the University of Massachusetts Amherst in 2014 and is now an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Valley Forge Military College in Wayne, Pennsylvania. Active in the American Association of University Professors and the Caucus for a New Political Science, his recent research projects include “Southie versus Roxbury: Crime, Welfare, and the Racialization of Massachusetts Gubernatorial Elections in the Post-Civil Rights Era” and “Sixteen Tons or, The Academy as the Company Store: Personal Stories and Popular Perceptions of the Student Loan Debt Crisis.”

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.