Philly’s Toynbee Tiles are slowly dying out. Will the Streets Dept. be able to resurrect a few?

The Streets Department cares about Philly’s street art. No, I’m not talking about Streets Dept., the photographer with 143,000 followers on Instagram, although Mr. Benner obviously cares a little bit about street art, too.

I mean the actual Streets Department, better known as those guys who try to fill potholes and pick up trash, and never hear the end of it when they don’t quite get it all. The department that’s its own weird mix of brawny guys who use their backs to pay the bills, wonky engineers and accountants trying to figure out how to stretch a shoestring budget to cover thousands of miles of roads.

Streets employees may be the least likely city workers to be found spending Sunday at the Barnes or catching a gallery opening on First Friday. And yet it’s probably the only city department that’s baked an art preservation clause into its standard, bid-out contracts.

The city’s paving agreements stipulate that paving contractors must halt resurfacing and notify a Streets engineer if they come across a Toynbee Tile, those strange mosaic messages embedded into the pavement across Philadelphia.

The Tiles are at once part of our local lore and art known the world over, the product of a South Philly man with a tenuous grip on reality and a tremendous amount of creativity. The tiles have inspired imitators and thieves alike, not to mention numerous news pieces and one award-winning documentary. And with all signs suggesting the mysterious Tiler has left the city for good, the tiles are becoming ever more rare and in danger of extinction in their native habitat, Philadelphia.

The Streets Department wants to save a few for posterity, before their slow resurfacing process destroys the few left remaining that have managed to survive years of city winters and SEPTA buses. For Tonybee fans, that’s reason for hope.

But this is also the Streets Department, whose other good intentions have paved a pothole-filled road to Philly’s trash-strewn hell. Can the cash-strapped agency figure out a final piece to the preservation puzzle? Can they figure out how to remove a Toynbee Tile, intact and on the cheap?

THE MYSTERY OF THE TOYNBEE TILES

“MURDER EVERY JOURNALIST. I BEG YOU.”

So exhorted one of the long lost Toynbee Tiles. The Tiles first started appearing on Philadelphia’s streets back in the early ‘80s.

The hand-made, linoleum tiles range in size from the size of a postcard to a license plate, with the occasional poster-sized piece. When the Tiler places them on highways, he elongates the letters to make them easier to read at high speeds, the way some highway markers do.

It’s the sort of attention to detail we can expect of a man possessed with an idea that wouldn’t just save humanity and create an utopia, but would bring back loved ones from beyond the grave.

That’s the theory pieced together by Philadelphia-based artist Justin Duerr, photographer Steve Weinik, and musician Colin Smith. Along with filmmaker Jon Foy, the trio cracked a mystery that bedeviled dozens of reporters, a small army of amateur sleuths, and countless pedestrians: Who is behind the Toynbee Tiles?

Foy’s award-winning documentary of that effort, “Resurrect Dead: The Mystery of the Toynbee Tiles“, answers that question and what the Tiler’s trying to say with his baffling asphalt aphorisms.

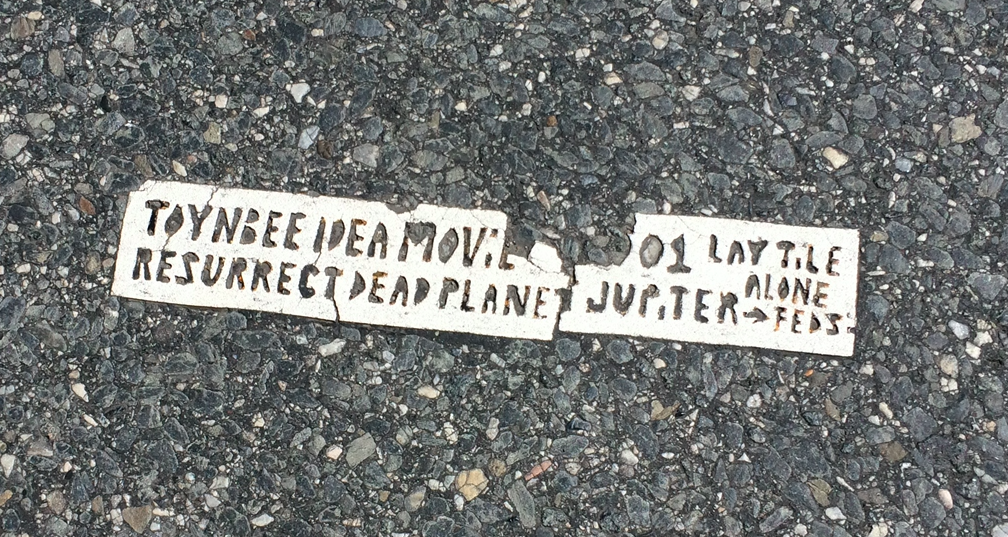

TOYNBEE IDEA

IN KUBRICK’S 2001

RESURRECT DEAD

ON PLANET JUPITER

That message, found on most Toynbee Tiles, is a jumble of science fiction and a philosopher’s aside. “Toynbee idea” likely refers to Arnold Toynbee, a British historian and philosopher, who once—as part of a larger argument against the existence of a soul—raised the specter of scientifically managing to bring back the deceased. To the Tiler’s addled—or inspired—mind, Stanley Kubrick’s “2001: a Space Odyssey” presented the way forward. The science fiction classic depicts a mission to Jupiter that ends in a famously trippy sequence: the astronaut, watching himself on his deathbed, and then suddenly reborn as the Star Child.

If you believed fervently in an idea as powerful as resurrection, you might grow to hate the journalists that ignored and mocked you, too. And you might try to find a way of bypassing the media gatekeepers to reach the public directly. In a time before the Internet, you might try shortwave radio. But then, unsatisfied by the ephemeral nature of broadcasts, you might opt for something more permanent, to literally embed your message in stone. Or at least asphalt.

That’s the theory, at least. Maybe the crackpot sci-fi scheme is just one part of a larger piece of performance art, convincing the world he’s crazy.

Most cities treat the Toynbee Tiles like any other graffiti. Chicago removes them the as soon as they can. Topeka, KS considers it public vandalism. In St. Louis, MO, the city’s streets director has at least considered saving the last tile. The tiles have sparked curiosity across the U.S., with sightings in New York City, Baltimore, Newark, Delaware and as far away as Chile.

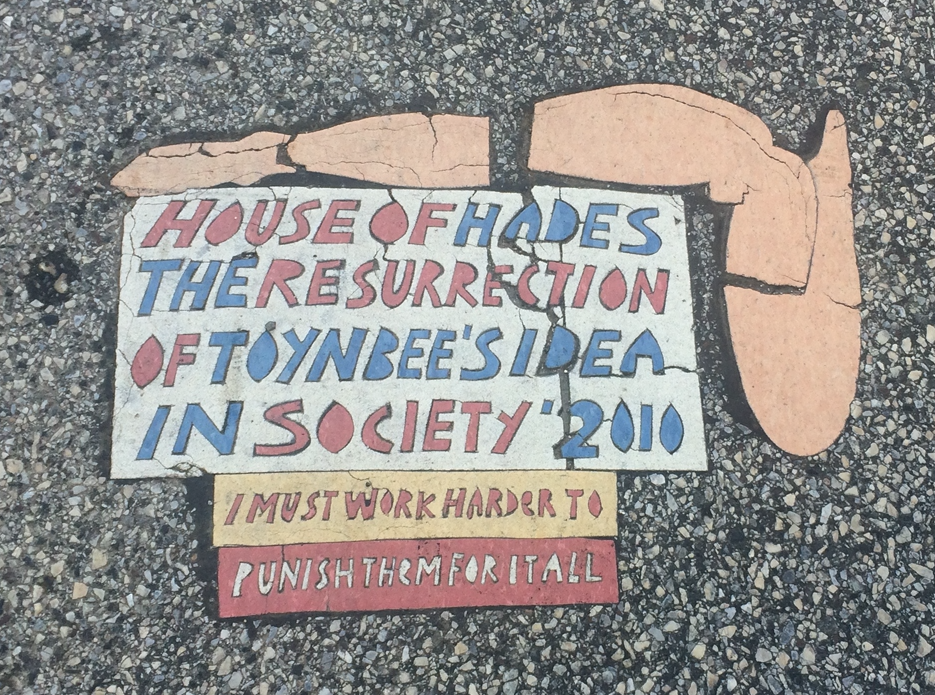

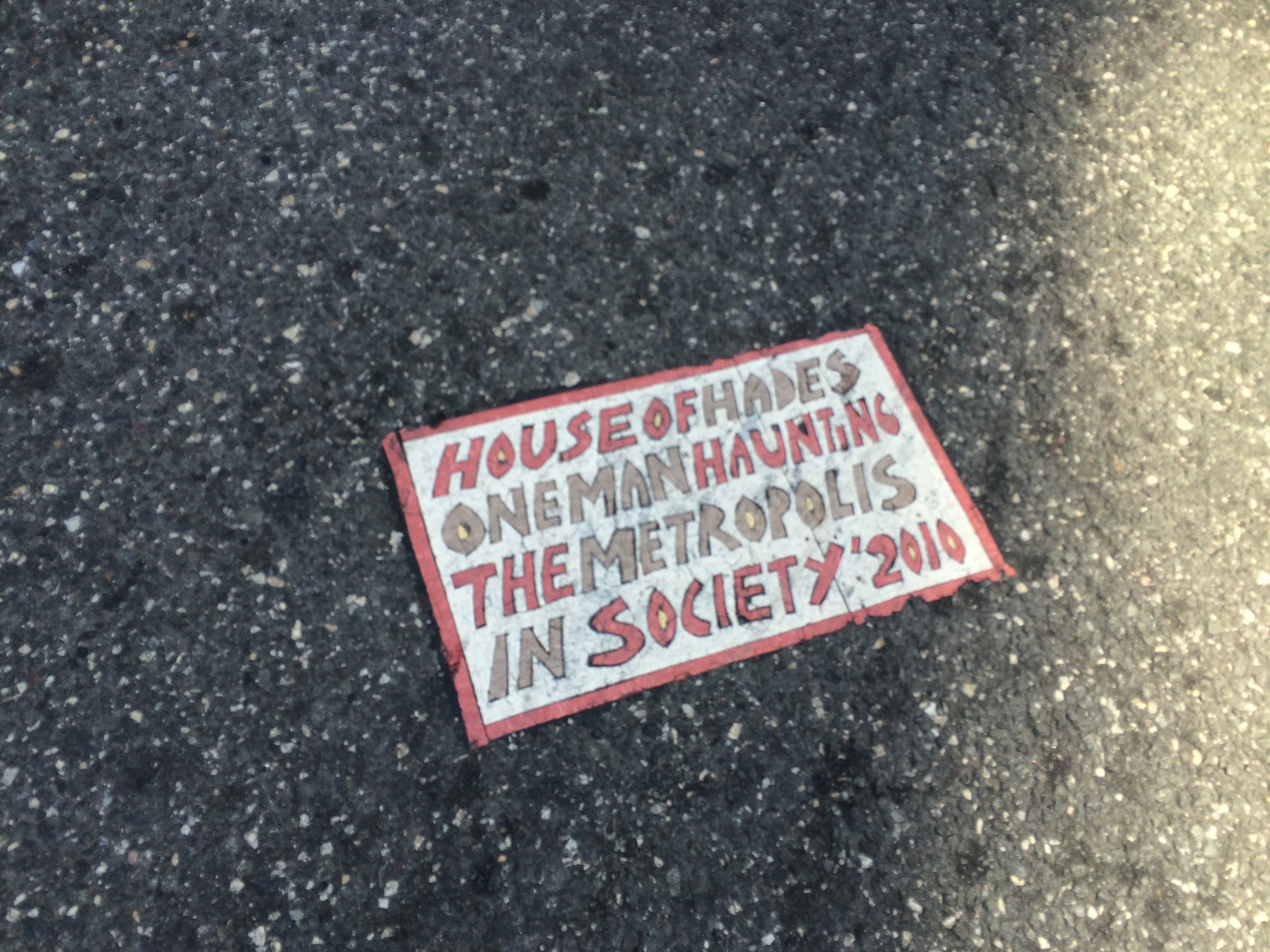

The Tiler has inspired copycats as well. Best known is the House of Hades, a project by an artist that Duerr believes is based in upstate New York. (Also worth noting: that guy purportedly uses asbestos tiles, so be careful if you’re the contractor tasked with removing them – airborne asbestos particles are cancerous.)

Closer to Philly, PennDOT treats the Toynbee Tiles like any other defect in the pavement. Just this summer, PennDOT crews unceremoniously ripped up and ground down a tile that graced the intersection of 18th and Market. When asked if the state agency ever considered preservation, PennDOT spokesman Charles Metzger dismissed the idea in an email. Metzger: “These tiles are not commissioned by the City or PennDOT. They are not part of any art project.” PennDOT affords no quarter for unwelcome surface invasions.

Steve Weinik, the photographer who helped solve the mystery, maintains a website on the Tiles, which includes a semi-regularly updated map of where the Tiles have been discovered. The map, replete with photos, shows where over 600 Tiles are, or once were. Increasingly, the photos are all that are left, says Weinik.

“Unfortunately, there was a lot of repaving, so there isn’t a ton of good ones left to preserve.”

CAN A PEDESTRIAN CITY DEPARTMENT SAVE SOME SPACEY STREET ART?

Over the last few years, more tiles have popped up around Margate, Ventnor and Atlantic City. Meanwhile, the last new tile in Philly was placed years ago, suggesting the mysterious man behind the tiles has retired to the beach.

To save the Tiles, couldn’t Philadelphia’s Streets Department just pave around them? After all, that’s what appears to have happened to a few tiles on Ventnor Avenue in Margate. But, according to Atlantic County public works department spokeswoman Linda Gilmore, no one at the department was familiar with the tiles, or the decision to spare them. The engineer who worked on the last repaving there passed away, and with him, the names of the contractors who might have been able to provide some insight.

But paving around won’t do, says Streets Commissioner David Perri. “If the street needs to be paved, the street needs to be paved.”

“Leaving them there and trying to pave around them creates seams and leaves weathered road surface in place, which invites potholes in the near future,” said Perri. Besides, exposed to the elements, especially Philly’s hot summers, the tiles bend, chip and warp. Simply leaving the tiles would amount to short stay of execution, not real preservation.

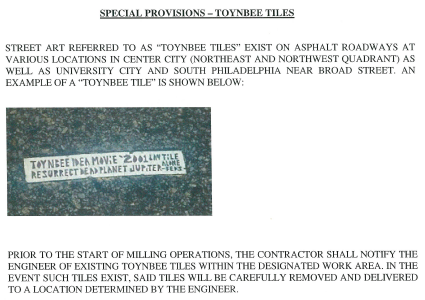

Streets Department spokeswoman Keisha McCarty-Skelton shared with me by email a screenshot of the special contract provision, which reads in pertinent part “STREET ART REFERRED TO AS ‘TOYNBEE TILES’ EXIST ON ASPHALT ROADWAYS AT VARIOUS LOCATIONS IN CENTER CITY (NORTHEAST AND NORTHWEST QUADRANT) AS WELL AS UNIVERSITY CITY AND SOUTH PHILADELPHIA NEAR BROAD STREET.”

It then includes a picture of a Toynbee Tile before continuing: “PRIOR TO THE START OF MILLING OPERATIONS, THE CONTRACTOR SHALL NOTIFY THE ENGINEER OF EXISTING TOYNBEE TILES WITHIN THE DESIGNATED WORK AREA. IN THE EVENT SUCH TILES EXIST, SAID TILES WILL BE CAREFULLY REMOVED AND DELIVERED TO A LOCATION DETERMINED BY THE ENGINEER.”

According to Perri, the Streets Department has yet to be contacted by a contractor regarding the special provision. Streets opted to rely on the contractors to self-report because “we weren’t going to send inspectors around to do inventory.”

However, since I first reached out to the Commissioner about this story, Perri says that Streets reviewed Weinik’s map and “started doing our own inventory so that they show up as a ‘conflict’ in our street opening system.”

But, he adds, “We have not found too many of them.”

Even if Streets finds one of the few remaining Philadelphia tiles worth preserving, it isn’t willing to do so at any cost. Perri is a well-respected bureaucrat and department head, not some kind of modern day urban Indiana Jones. “We’re not sure if it’s worth it financially to preserve them.”

Streets will save one or two of the Toynbee Tiles only if there is a fast and affordable method for removing them. Perri says the department hasn’t spent any time trying to figure out what, so far, has been a purely academic question.

FROM PROFESSIONAL STREET ENGINEERS TO AMATEUR ART HISTORIANS

“Finding an easy, smart way for a contractor to remove them is the problem,” says Ariel Ben-Amos. Ben Amos is the man who set all this in motion. After watching Resurrect Dead, Ben-Amos, then an employee in the Mayor’s Office of Transportation and Utilities, reached out to Perri about the possibility for preservation.

Perri was open to the idea. “I love the offbeat stuff that comes with the job and is uniquely Philadelphia,” he says. Together, they managed to integrate the removal of street art into the standard paving contract.

The next step: finding a place for it. Ben-Amos reached out to Weinik, and together they approached the Philadelphia History Museum at the Atwater Kent. Kristin Froelhich, Director of the Collection at the museum, started to put together the paperwork to allow the Museum to take ownership of City property, i.e., the chunk of asphalt holding a Toynbee Tile.

Now, all they had to do was figure out how to actually remove a tile. “Milling around them is difficult, that’s the hard part,” says Ben-Amos.

But before Ben-Amos could figure that out, a too-tempting job opened up at the Water Department for the Penn graduate. Ben-Amos left MOTU, handing off all his important projects to his colleagues to take over. The quirky, perhaps quixotic, street art preservation project fell by the wayside. That was back in 2013.

And so the preservation provision has sat largely ignored without a champion and enforcer to see it through, and without an easy answer to give to contractors.

“Milling operations are pretty primitive. They use very blunt tools,” says Perri. “If this requires a surgeon’s scalpel to pull out, it may cost more than any artistic value it might have.”

Not quite a scalpel, but there have been reports of thieves using little more than a putty knives to pull Toynbee Tiles out of the pavement.

If some street Thomas Crown can pluck a tile, one hopes the professional engineers at Streets can, too. Maybe they can practice on some of the other street-embedded art around town, which haven’t been designated for preservation. Perhaps one of the Stikman – another street art project common on Philly’s streets – could be sacrificed for the sake of preservation science?

DOES A RESURRECTED TILE STILL HAVE A SOUL?

Even if Streets can manage to save a few Toynbee Tiles, should they?

Isn’t part of what makes street art special is its ephemerality? Or that its fleeting nature stems from street art’s implicit disinterest in societal approval? The Toynbee project, especially, was an attempt by the Tiler to get his insane message out without government censoring or media mockery. Writing a story about a government agency’s attempt to preserve the Tiles in a government museum has been ironic, to say the least.

If art is a communicative act meant to convey meaning and sense to others, then perhaps the Tiles should be preserved, if you consider this message – or the hermeneutical reading of what the Tiles said in the context of the times – worth another look.

Can street art ever still say what it’s meant to say when it’s removed from the verbiage of the street? Or does it become a word suddenly without a sentence, a limpid noun suddenly cast off from the concrete context upon which it was predicated?

I put the question of preservation of street art to RJ Rushmore, who recently curated a Stikman exhibit at LMMNL Gallery in Fishtown. “Usually when people ask me this question, it’s because someone chopped off a piece by Banksy,” Rushmore begins.

“That’s… like ripping up a Picasso, [and] trying to sell 100 scraps of a Picasso.”

Rushmore notes that context can matter, but expands that context to include the intentions behind removal.

“For someone like Banksy, it’s all about the context. A character next to the Hustler Strip club – so it’s some guy with sad flowers – it doesn’t work anywhere else,” he says.

But, “with Stikman and the Toynbee Tiles, I think it’s a little bit different.”

“This is someone saying: I’m going to destroy this thing… should I throw it in the trash or no? “ Rushmore asks before answering, “And so, I say, sure, preserve it.”

“I think it’s one of the few areas where preservation of street art can be a great thing.”

Or perhaps the importance of the tiles isn’t found in their inane ramblings, or their context in the street. “Some people go to meditation…” Justin Duerr says, wondering if this has become a meditative act for the Tiler.

Duerr, arguably the real protagonist of Resurrect Dead, recently led an Atlas Obscura tour of the Toynbee Tiles along with Weinik. Duerr and Weinik have probably spent more time thinking about the tiles than anyone else. But even they seem sanguine about the possibility of the tiles being lost forever. It seems as though, by solving the mystery of the Tiler, they also broke his spell over them.

That isn’t to say they don’t want to see the tiles preserved, though.

“We appreciate the ephemerality of the tiles, and seeing them in context, but still think that preserving them is a cool idea,” wrote Weinik in an email.

“By our best guess, the Tiler chose his method to make them as permanent as possible, so we don’t think he’d mind ripping them out and putting them on display. It keeps the message alive.”

According to Weinik, there may just be two good examples of the larger tiles left in Philly for possible preservation: one at 34th and Chestnut and another next to the Allegheny El stop on Kensington Avenue. But even those have seen better days.

Perhaps what this oddball collection of preservationists are trying to do is no different from the old natural history museums, where you can still find embalmed specimens of long extinct species. We can’t see a passenger pigeon in the wild anymore, but there’s a perfectly stuffed one at the Academy of Natural Sciences.

Toynbee Tiles are going the way of the passenger pigeon. It’s up to Streets, a department that regularly deals with 19th century infrastructure, to do some 19th century conservation, so later generations might appreciate this quirk, a time before the internet, a time when a Philadelphian could argue that planting tiles in the street was a more effective means of getting a message out than any other medium.

Then again, it’s 2015, decades since the first tile was laid, and you’re reading about Tonybee’s Idea still. Maybe the Tiler was on to something.

Maybe I’ll see you on Jupiter.

Want to know more about the Toynbee Tiles? Check out this episode of WHYY’s Friday Arts from 2012.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.