Philly neighborhoods forum asks: How can we achieve a fair future?

When you bring 100 Philadelphians together to discuss how to improve communities for long-term residents and new neighbors alike, you get hundreds of more questions.

-

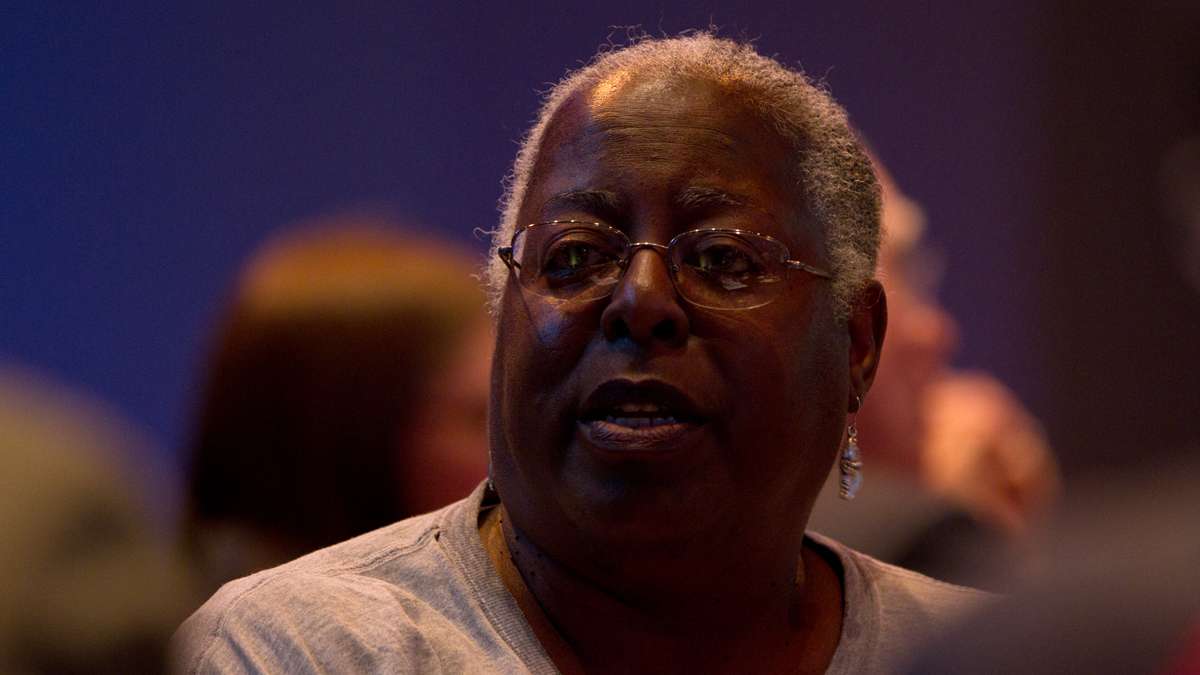

Attendees discuss their neighborhood experiences in small groups at the Speak Easy forum 'Philadelphia Neighborhoods in Flux.' (Ifanyi Bell/for NewsWorks)

-

The level of sound rose only gradually as civil and respectful conversations took shape around the room. (Ifanyi Bell/for NewsWorks)

-

Discussions focused on person stories and lived experiences. (Ifanyi Bell/for NewsWorks)

-

There were lifetimers and new residents, young and old, some who had lived in the city for more than a decade but still felt 'new,' some who had stayed put their whole lives, and some who moved around the city or even left only to return. (Ifanyi Bell/for NewsWorks)

-

Some topics that stood out included feelings of helplessness against crime, rising rents, property taxes and tax breaks for developers. (Ifanyi Bell/for NewsWorks)

-

Some areas of concern included equitable development practices, L&I and zoning oversight, fair banking practices, the Land Bank, and funding for city schools. (Ifanyi Bell/for NewsWorks)

-

It was suggested that the idea of 'community' is different for younger residents and older residents. Young newcomers tend to care about the whole city, whereas, longer-term residents are more tuned into the activity on the block. (Ifanyi Bell/for NewsWorks)

-

Some of the younger attendees expressed a desire to understand their role in the gentrification pressures in the city. (Ifanyi Bell/for NewsWorks)

-

'Philadelphia Neighborhoods in Flux' is the first in a series of Speak Easy forums hosted by WHYY. (Ifanyi Bell/for NewsWorks)

What do you get when you put 100 Philadelphians together in a room to discuss how to improve their communities for long-term residents and new neighbors alike? You get hundreds of more questions and nearly limitless opinions.

That’s what Speak Easy did on April 21 at WHYY studios, where we asked a collection of complete strangers from across the city: What does a fair future look like to you? And what do you need city leadership to know to help you achieve it?

Areas of interest that stood out included:

- Feelings of helplessness against crime

- Rent control

- Taxes! (property tax vs. land value tax; abatements; anti-speculation taxes)

- Community benefits agreements with developers

- School district support for immigrant and refugee students

- L&I and zoning oversight

- Community banking, lending

- The Land Bank

- Councilmanic prerogative

With a focus on personal stories and experiences, five guest speakers and the room full of attendees started an inter-neighborhood conversation about the opportunities, the pressures and the pain points of gentrification — a word that seems to mean dozens of things at once, a force largely positive to some, completely negative to others, with a whole lot of discomfort in between.

What the room agreed on is that we’re all in this together. Everyone in the room wanted to see Philadelphia succeed, and no one seemed to want any disadvantaged residents to miss out. Maybe Philadelphia’s self-perception as the City of Neighborhoods works against us when those neighborhoods aren’t working together toward a common goal.

First-person perspective

Jamie Moffett, founder of Kensington Renewal, started the evening off by putting the current state of Philadelphia’s changing neighborhoods into a historical context. Since the development of the Society Hill towers (and the displacement of the people who used to live on the site), development has spread outward. It seems to hit a new neighborhood about every seven to 10 years, Moffett said. “You can almost plot it on a map.”

(Dylan Gottlieb wrote a great summary of this process for the Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia.)

Next De’Wayne Drummond, who calls gentrification the “G-spot” (“because it’s a touchy feeling”), described his experience as a lifelong resident of Mantua. Drummond has seen the highs and the lows — from the disappearance of his neighborhood’s supermarket and the failure of city schools, to new recent successes, such as the formation of the Mantua Civic Association, of which he is president, and the designation of the neighborhood as a federal Promise Zone.

Drummond has helped build a growing sense of community engagement. “That was our first priority,” he said, “putting civics back in our community.”

“I do see a change in Mantua. I do see that there’s hope,” he said. “There is hope that long-standing, long-term residents will have a chance to live in their house, and their generations after them, and they won’t have to face no gentrification.”

Jill Betters, a neighborhood leader who spoke as a young person with years of experience as a renter, said, “I am in some ways a poster child for ‘New Philadelphia.'”

In Fishtown, she said, she lives in the epicenter of the city’s newbie/lifer conflict, where, at its worst, long-time residents see young newcomers as tearing at the fabric of their community, and those newcomers see their neighbors as old-timers who don’t know what’s good for them.

Betters has tried to bridge that divide in her work with the Fishtown Neighbors Association. “The long-term residents are the underpinning of the community,” she said. “I am less when they are not there. They tell me all the things that I need to know in a way that newer residents won’t be able to tell me.”

Speaker Penelope Giles said that, as a kid growing up in Francisville, she didn’t know that her middle-class African-American neighborhood was being defeated by inequitable zoning decisions and long-standing patterns of segregation. When she returned as an adult, her home had lost its economic presence, and she saw the restoration of Ridge Avenue as a commercial corridor as the key to the neighborhood’s renaissance.

“What happened to our neighborhood is what happened to just about every neighborhood of color across the U.S. that began to establish as middle class neighborhoods in the ’30s and ’40s,” she said. “All these neighborhoods were driven into economic depression.”

As president of the Francisville Neighborhood Development Corporation, Giles said, “The first step is to regain economic diversity.” She has also been pushing for experimenting with a tax based on land value rather than the current property tax model.

It doesn’t matter what ethnic groups live in these communities, she said. It’s the poverty that leads to bad human behavior and lack of opportunity.

Rounding out the group was Dai Lai Htoo, a Burmese refugee who grew up in Thailand and came to South Philly in 2008. He lives with many south Asian immigrants along the S. 7th Street commercial corridor.

“I see change every year,” he said. “People move in and out. The neighborhood is never stable.”

Resettlement services help immigrant families find a place to live, but when the support runs out after a few months, he said, rising rents force most of them to move to a more affordable situation, often across state lines.

Dai Lai, who works with the School District of Philadelphia as a bilingual counselor, supporting parents of immigrant students, said Philly schools don’t have the resources to adequately support immigrant students.

“I would like the new immigrant families in South Philadelphia to feel connected to the city, to feel like home,” he said.

One city, a multiplicity of experiences and biases

Apart from the neighborhoods represented by the speakers, participants came from all over: Belmont, Brewerytown, Cedar Park, Center City, Chestnut Hill, East Passyunk, Fitler Square, the Gayborhood, Germantown, Logan Square, Manayunk, Mt. Airy, North Philly, Northern Liberties, Old City, Point Breeze, Powelton, Queen Village, Rittenhouse, Roxborough, Society Hill, South Philly, Spring Garden, Strawberry Mansion, Tioga, Walnut Hill, West Oak Lane, West Philly, Wynnfield.

On display was an incredible diversity of experience — and a room full of residents whose stories were all equally valid and important. There were lifetimers and new residents, young and old, some who had lived in the city for more than a decade but still felt “new,” some who had stayed put their whole lives, and some who moved around the city or even left only to return.

Some of the long-time residents had experienced more ethnic diversity when they were children, citing gentrification as the reason for today’s ethnic segregation. Others grew up in racially segregated neighborhoods and now, only more recently, live in more racially and economically diverse areas.

“I would like to see integrated communities, but people flock to be around people they want to be around,” said one participant. “People may come into one neighborhood and change it, and the people that leave will go to other neighborhoods, and those neighborhoods will change.”

Even within racial enclaves, class issues compound views of neighborhood decline or improvement. Two African-American women described situations in which they were seen as “Uncle Toms,” in both declining and gentrifying neighborhoods. Outreach can be very challenging, even with attempts to be inclusive, stunting community organization.

The issue of mobility — voluntary and involuntary — dominated much of the discussion. Some residents were distressed that more and more “regular” people were moving out of their neighborhoods, that working people were being priced out of their homes.

This draws attention to one of the challenges of any discussion about neighborhoods in flux — the words we use and the biases underlying them.

One table discussed the phrase Betters used, “New Philadelphia,” which they considered to be pejorative, pitting the values of existing residents against those of newer residents.

Another example was the “innovation” of splashy projects heralded in the media, the effects of which might pale in comparison to the incremental progress made to keep communities alive by long-time residents. One participant said that the media has moved from “poverty pimping” to “innovation pimping.”

So, given all of this, how can we work together to make sure everyone can participate in Philadelphia’s upswing?

Some themes came up again and again from table to table. Here are some paraphrased comments from around the room.

Fair and equitable development

Developers may be investing where no one else is, but often they are just putting up new buildings. The vacant lots and drug activity next door continue.

One resident described a helplessness felt by many others in the room. She said she sees development happening all around her, but not where she lives. There’s drug activity, on her block, but she’s scared that if she says anything, she’ll be endangered as a “snitch.”

There should be more community oversight on L&I and zoning decisions, which seem to benefit business interests and not community interests.

It’s too difficult to invest in a challenged neighborhood through the formal banking system. Mortgages and construction loans are difficult to secure in neighborhoods where homes and land values are less that the minimum amount a homeowner must borrow.

Some said we need more financing for rehabbing and less for new development.

Older vs younger

Some younger participants, new to Philadelphia, talked about their internal struggles to understand their role in gentrification despite their positive intents — or simply their need to live somewhere they can afford.

The definition of “community” for Millennials seems to be different than among older folks. Young newcomers tend to care about the big picture, e.g., What can the city do? What benefits the city? — whereas, longer-term residents are more tuned into the small, neighborly activity on the block.

Even the word “millennial” came under fire. We say that “millennial” refers to an age group but really, when we talk about Millennials, we’re usually talking about college-educated, white people with disposable income, not a 25-year-old single mother who’s lived in South Philly her whole life. Why is this?

Renter vs homeowner

Newcomers, especially renters, may not feel “allowed to comment” on the goings-on in a neighborhood.

One resident said that, in his neighborhood, only when his prospective neighbors learned he was going to buy a house did they seem to trust and accept him.

This tension is relieved only when renters and owners talk to each other. “How do we have that first conversation?” someone asked.

Tax policy

Many attendees discussed the failure of the city to find an equitable property tax solution. As it stands now, said some, investment in poorer parts of town is discouraged, yet early investors are punished by eventual property tax increases.

Tax abatements came up again and again. Many said the number of abatements should be limited. People have no incentive to stay after the abatement ends and their taxes kick in. Homeowners pay higher property taxes because of the development, but developers don’t pay.

One proposal that kept coming up was from a group advocating “Development Without Displacement,” a campaign to raise an anti-speculation tax by raising the realty transfer tax by 1.5% on “flipped” homes (properties that developers buy and sell within two years).

Someone suggested that citizens should pull together to get the tax breaks that go to developers.

What can the city do?

Philadelphia needs to be better at collecting back taxes, punishing tax delinquents, driving out the slumlord mentality, and incentivizing landowners to maintain and develop abandoned properties.

There was some dispute among attendees about a perceived new layer of bureaucracy created by the Land Bank — the requirement of city council approval to buy properties. (there was some dispute over how the land bank worked, and whether it was a good thing or not)

Building affordable housing can help avoid pricing people out of their neighborhoods, but the city needs clearer rules about, and better enforcement of, affordable housing requirements for new construction. A builder may promise mixed-income housing, but will the ratio of market-rate to lower-income options be enforced?

The city needs to fully enforce community benefits agreements. CBAs can help developers and anchor institutions, e.g., universities and corporations, achieve more responsible development by creating local jobs and expanding neighborhood services, but one participant noted that the actual agreements are weak. Lack of funding allows developers to “cherry pick” where they comply.

There was an acknowledgement that exploring inclusionary zoning should include hearing from builders about what they see as the challenges of doing that in Philadelphia.

One attendee said we need to help the homeless who we’ve pushed out of Center City.

Some participants said the city needs to make things easier for immigrant families

There was some feeling that the next mayor should draw attention to corruption that can stem from city councilmembers control over development projects in their home districts, known as councilmanic prerogative.

There were several calls to raise the minimum wage.

There were several calls to fix the funding crisis for Philadelphia’s neighborhood schools.

Some participants said the city should stabilize rents like in New York City.

The city could do a better job at informing long-term residents in struggling communities about programs to assist them with home improvement and taxes.

Not everyone came together philosophically, but by simply being together in the same space, jusst for one night, I hope the participants left feeling a little closer to each other in a physical sense. One idea rang out clear: Neighborhoods must work together to achieve equitable growth across Philadelphia. The notion of the insular Philadelphia neighborhood looking out for itself seemed anathema to the kind of work proposed by members of the audience. Creating a strong network of existing (and new) neighborhood associations, and institutions serving different populations in need, would work against the pressures that lead to segregation and stagnation.

—

Jared Brey of PlanPhilly was in attendance and put together a guide to resources in the city, which addresses a number of the problems attendees referred to.

Special thanks to the Penn Project for Civic Engagement, which helped organize a team of moderators for the group discussions at the event, including Marjorie Anderson, Brian Armstead, Andrew Goodman, Rosalind Spigel, Terrill Thompson and Josh Warner.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.