Philadelphia’s Institute of Contemporary Art shows the contemporary influence of the Shakers

“A World in the Making: The Shakers” examines the historic religious sect that has all but disappeared.

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

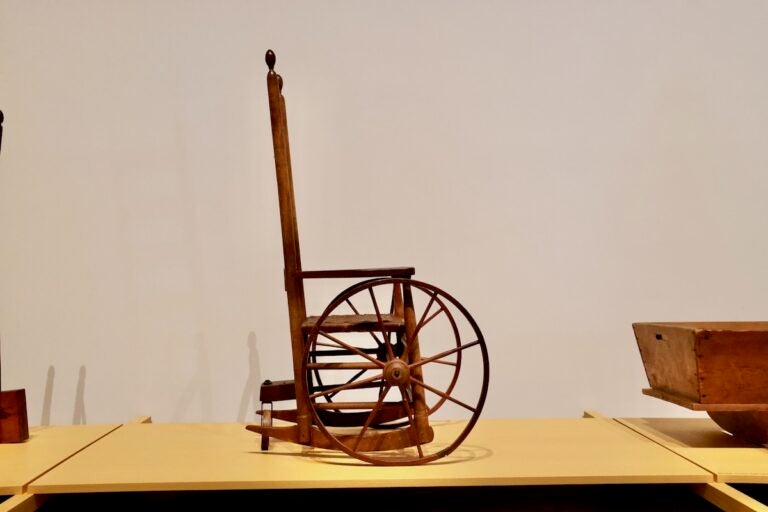

An art exhibition about the Shakers, also known as The United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing, would naturally have furniture. The Institute of Contemporary Art has plenty: ladder chairs, rocking chairs, swivel chairs, side tables, bureaus, dressers and the hand tools that made them.

“I like to think of the furniture as a gateway drug to the Shakers,” said co-curator Shoshana Resnikoff, of the Milwaukee Art Museum.

Some of the chairs are hung on the gallery walls so visitors can get up close and see the masterful details. One simple side table is made from five species of wood, each one selected to play a specific role in furniture making.

“These are very complex pieces of furniture. They are deceptively simple,” Resnikoff said. “It’s a gateway for people to begin to understand their community and their belief system.”

“A World in the Making: The Shakers,” opening this weekend at the ICA, is a collaborative traveling exhibition of the ICA, the Milwaukee Art Museum and the Vitra Design Museum of Rhein, Germany, with significant contributions from the Shaker Museum in New Lebanon, New York.

The contemporary influence of Shakers

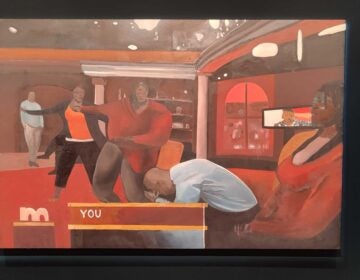

The exhibition is an overview of the history and spiritual philosophy of the separatist Christian sect founded in 1747 and now nearly disappeared. According to NPR, there are now exactly three individuals who identify as Shakers. It is also a contemporary response to their legacy. The exhibition features seven artists making new work inspired by the Shakers.

Chris Liljenberg Halstrøm, a Danish furniture designer and artist, came upon a quote from Shaker founder Ann Lee that resonated deeply with her: “Hands to work, hearts to God.”

“I think that’s the most beautiful quote I’ve ever heard. It’s really how I feel,” she said. “I think most artists work like that. We create something to put into the world to somehow, hopefully, make a better world.”

The Shakers’ belief system regarded work as a kind of prayer: slow, thoughtful and honest, with every gesture intentional. In kind, Halstrøm built a textile workstation with a simple table and stool, with even the scissors and thread spools made singularly by hand.

The furniture faces a large wall hanging of embroidered color fields that echo the blue color Shakers typically used for their meeting houses.

“It has over 130,000 stitches and I hand stitched it myself,” Halstrøm said. “It sounds like an easy task, to embroider. It’s really tough. I spent five months making this piece. So, it does become like a prayer to make my work.”

It may seem like an oxymoron for the Institute of Contemporary Art to feature a show which is, in many ways, historical. Director Johanna Burton said there are three reasons to host the exhibition, including the fact that the Shakers’ quest to find a better model for living and working is in line with the ICA’s mission of arts presentation.

“Secondly, we follow artists, and artists take us back to the Shakers,” she said. “And third, we really value the opportunity to always confuse you.”

The Shakers are having a moment

The exhibition comes at the same time a major motion picture about the origins of the Shakers arrives in cinemas. “The Testament of Ann Lee” is a biographical musical about the Shaker founder who led converts from England to upstate New York in the 18th century.

The Shakers were religious cousins to the sects like the Quakers and Amish who preferred a plain lifestyle but were unique in their sometimes-ecstatic physical worship. They were once dubbed by outsiders as the “Shaking Quakers,” which they ultimately adopted as simply Shakers.

In the 1984 PBS documentary “The Shakers: Hands to Work, Hearts to God” by Ken Burns, Sister Mildred Barker demonstrated for the camera their spiritual dancing technique.

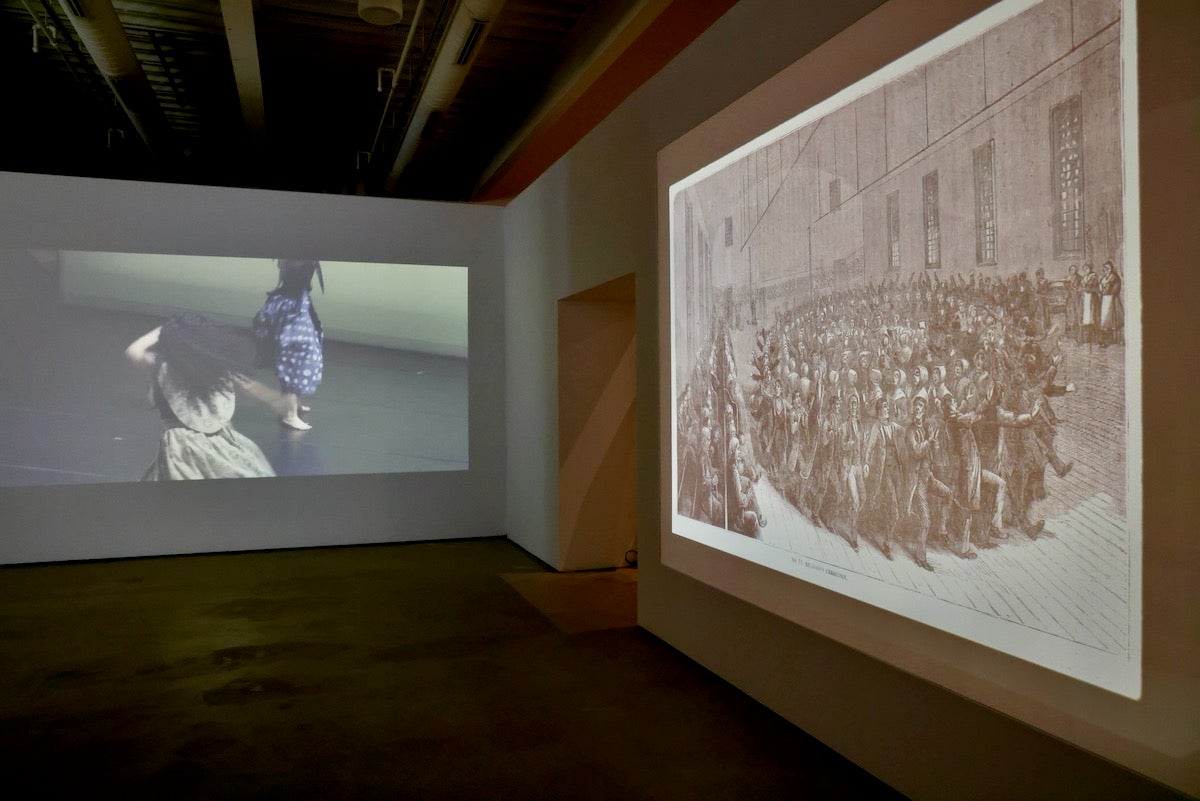

“A World in the Making” featured video footage of a 2022 performance of choreographer Reggie Wilson’s “Power,” based on the ecstatic movements of Shaker dance.

Wilson was inspired by the 19th-century Philadelphian Rebecca Cox Jackson, the only Black woman to found a Shaker community and the only one to be set in an urban environment.

While Shaker founder Ann Lee was illiterate and the early years of the movement left behind no written records, Jackson wrote the autobiography “Gifts of Power” in the 1860s, describing her spiritual visions and her introduction to the Shakers’ whole-body worship.

“The power of God came to me like the waves of the sea, and caused me to move back and forth under the mighty waters,” she wrote. “They all seemed to look as if they were looking into the spiritual world … as if they were living to live forever.”

Doing business in the world they were not part of

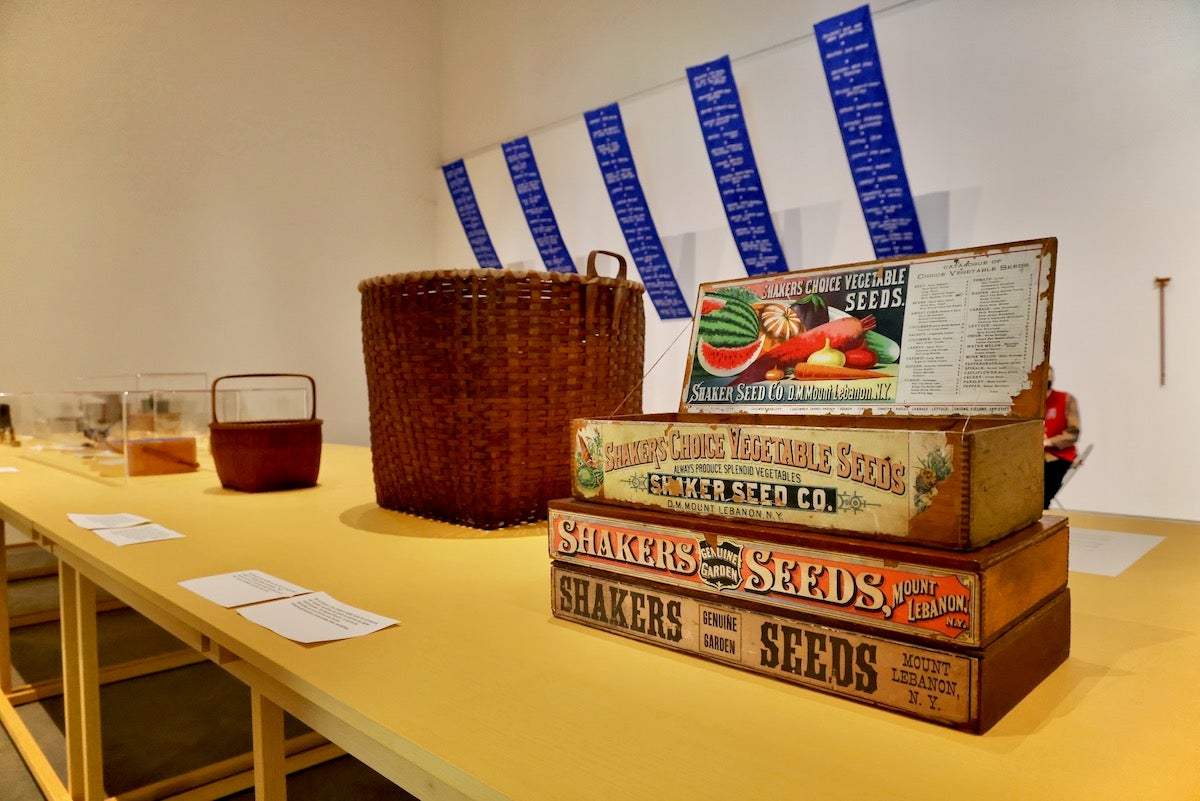

The exhibition shows the Shakers as inventive and entrepreneurial. They were the first to develop seed packets, those little envelopes with small portions of seeds for retail sale so customers would not have to buy seeds by the pound. They sold authentic herbal medicines in the 19th century when the market was flooded with hoaxes.

Brother Theodore Bates, of the Watervliet Shaker community in New York, developed the flat broom in 1798, still a mainstay for keeping house.

“Cleaning was wild before then. A circular broom seems really horrible,” said co-curator Hallie Ringle, of the ICA. “That’s something that’s been largely unimproved upon. Go to the hardware store and you can still buy a flat broom. It still works quite well.”

The exhibition shows seeming contradictions in the Shaker sect. They valued communal egalitarianism but maintained gendered roles. They staunchly removed themselves from secular society but actively pursued trade with it. They adhered to traditional values but were progressive artisans.

Ringle said “A World in the Making” is meant to neither glorify nor criticize Shakers, but to show how they attempted to make a world of their own.

“Shakers believed in simplicity and design, but they were also capitalists,” she said. “Even though they lived in a communal, communist society, they were deeply involved in capitalism. They were making furniture and medicines and seed packets to sell to the world.”

“A World in the Making: The Shaker” runs at the Institution of Contemporary Art until Aug. 9.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.