The outsider who came in: Henri Rousseau retrospective opens at Philly’s Barnes Foundation

The celebrated French post-impressionist was dismissed during his lifetime as “naive,” but held many secrets.

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

Known for his strange jungle scenes and dreamscapes, Henri Rousseau was a self-taught artist in late 19th-century Paris who struggled to be recognized his entire career.

His life was burdened with debt and criminal prosecution. When he was able to rise from obscurity, he was ridiculed. Now, his works are collected by nearly every major art museum in the world.

“Rousseau’s ambition outstripped his success in his lifetime,” said curator Nancy Ireson of the Barnes Foundation.

“Rousseau had terrible things said about him in the press. Journalists said that he painted with his feet, with his eyes closed. They called him all sorts of things. He didn’t sell his works,” she said. “Yet he keeps making art. He clearly has this unshakable self-belief.”

“Henri Rousseau: A Painter’s Secrets” is a major retrospective featuring almost 60 paintings from institutions around the world. It was put together by the Barnes Foundation, which has the largest collection of Rousseau paintings in the world, and the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris, with the second-largest.

Per the title, Rousseau was secretive both in his life and his work. Relatively little is known about him, considering his status today as a major artist.

Rousseau’s turbulent life

While growing up, his family lost their home in Laval, France, to debts and they lived in boarding houses. As a young man, he worked for a lawyer and began studying law but was convicted of embezzling money from his employer, then joined the army to avoid prison.

Rousseau worked most of his life as a low-level customs clerk in Paris, retiring in his 50s to paint full-time. He continued to run afoul of the law for unpaid debts on art supplies and for bank fraud, for which he was briefly imprisoned.

“He was not an honest man,” said Christopher Green, who co-curated the exhibition with Ireson.

“He was passing false checks with a friend of his who devised a rather complicated fraud,” he said. “The advocate who spoke for him held up one of his pictures in the court and said, ‘Could somebody who painted a picture like this really have known what a check was?’”

Rousseau likely knowingly leveraged his reputation as a naive artist for leniency, and it worked. The judge gave him a suspended sentence.

Paintings full of mystery

The “Secrets” of the exhibition title also refers to the canvases Rousseau painted, which have more questions than answers.

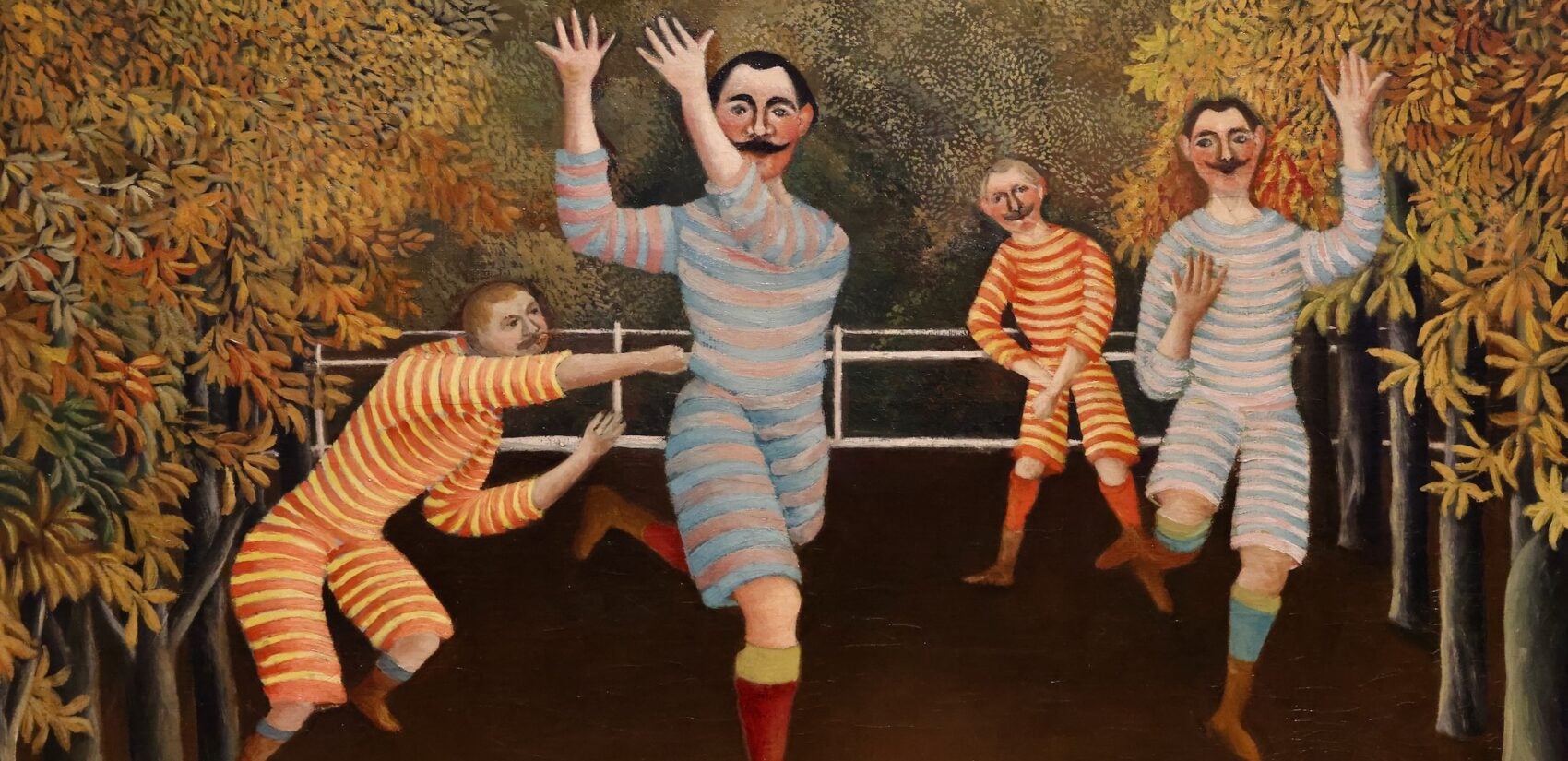

His flattened compositions have the simplicity of folk art. Most of the faces of his figures are facing squarely forward, and with rare exception, nobody is seen in profile.

His compositions also show a sophisticated draftsmanship, precise brushwork and inspired use of color. His famous “The Sleeping Gypsy,” borrowed from the Museum of Modern Art in New York, features a multicolored pinstriped dress, echoed by her hair and the strings of a lute lying beside her. In some of his nighttime jungle paintings, the background foliage is layered black on black, creating subtle shifts of depth.

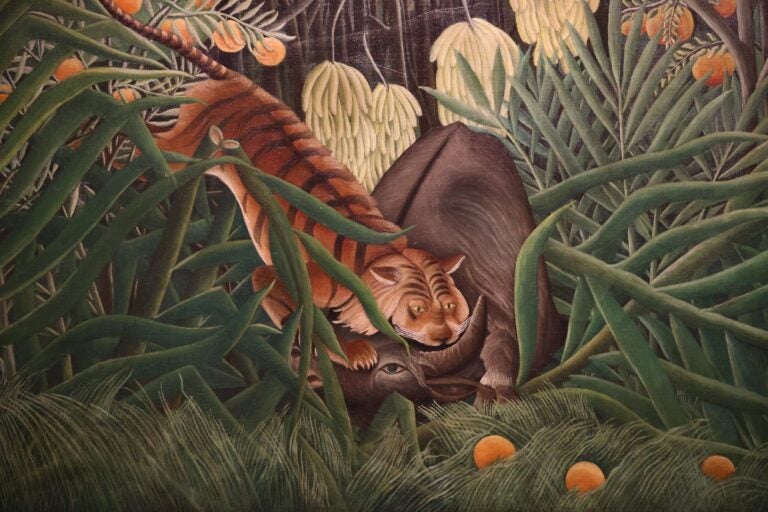

Almost all his paintings have an element of fantasy. The jungle paintings, which gained popularity toward the end of his life, have bizarre shifts of perspective and proportion, with gigantic flowers, trees that don’t quite make sense, deformed animals and incongruous figures, such as an American Indigenous person fighting a gorilla in what seems to be a botanical garden.

Rousseau never traveled outside of France and had no idea what a jungle actually looked like.

“What we do know is that Rousseau was really inspired by visits to the botanical gardens in Paris,” Ireson said. “He went often to the Jardin des Plantes, which is in the city, and there he would enter the hot houses. He really loved seeing those different species of plant.”

Green described Rousseau as a story giver, not a storyteller.

“He gives you the materials for a story, but he doesn’t necessarily tell you how you’re going to tell this to yourself,” he said. “It’s very suggestive and sometimes quite ambiguous.”

Posthumous recognition

Despite personal and professional setbacks, Rousseau remained steadfast in his own talent.

“It’s just extraordinary, the chutzpah of the man. The complete refusal ever to be discouraged,” Green said. “It can only come from a faith in what he was doing”

It was 15 years after Rousseau’s death, in 1910, before his talents were recognized widely, and even that was due to dealmaking. Berthe “Comtesse” de Delaunay sold “The Snake Charmer” to collector Jacques Doucet on the condition that upon the buyer’s death, the painting would be bequeathed to the Louvre Museum, which it was in 1925. Once in France’s national collection, Rousseau’s reputation for the next century was secured.

“Henri Rousseau: A Painter’s Secrets” will be on view until Feb. 22, 2026.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.