PFAS chemicals have contaminated 17 sites in Pennsylvania, data show

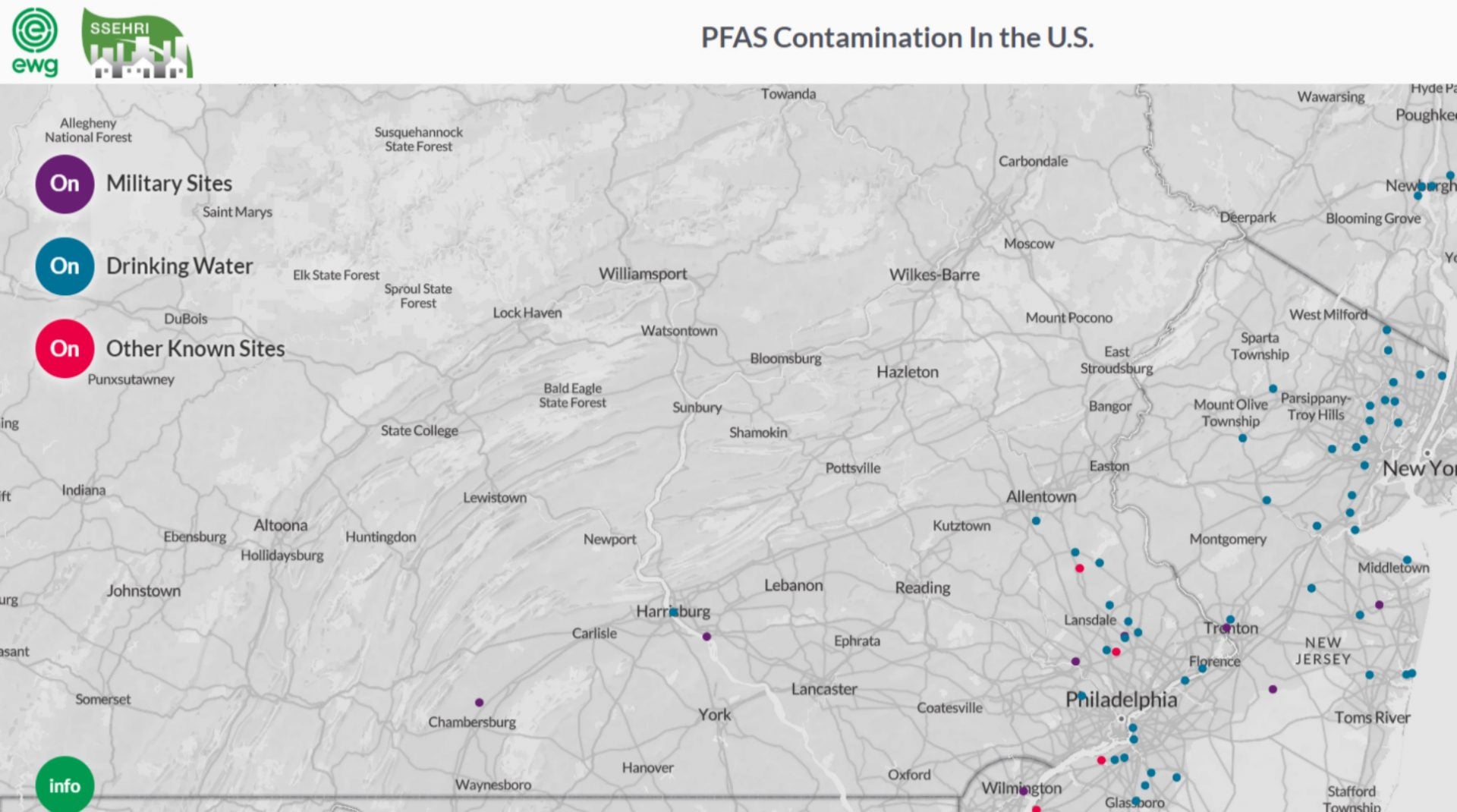

Mapping of public data shows PFAS-contaminated sites exist across the country.

In this Aug. 1, 2018 photo weeds engulf a playground at housing section of the former Naval Air Warfare Center Warminster in Warminster, Pa. In Warminster and surrounding towns in eastern Pennsylvania, and at other sites around the United States, the foams once used routinely in firefighting training at military bases contained per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS. (Matt Rourke/AP Photo)

This article originally appeared on StateImpact Pennsylvania.

—

Seventeen sites in Pennsylvania have been contaminated by PFAS chemicals in recent years, and are still likely to contain at least some of the toxic material even if water supplies there have been treated by local authorities, according to data released by a national advocacy group on Monday.

Environmental Working Group compiled PFAS reports from local utilities, the Department of Defense, and researchers at Northeastern University, and presented the information in a national map showing public water systems, military bases, civilian airports, industrial plants and dumps where contamination has been found at various times since 2013.

The utilities include one in the eastern Pennsylvania town of Horsham where five PFAS chemicals, including PFOA and PFOS, were detected at more than 44 million parts per trillion (ppt) in 2014, thousands of times higher than a level recommended — but not required — by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency as being protective of human health.

Horsham officials say they have since cut PFAS levels to below the recommended health limit by installing carbon filters. Public and private water wells in the Horsham area have been contaminated with high PFAS levels because the chemicals were a component of firefighting foam used by the military on two nearby bases.

Aqua, an investor-owned utility that also serves Horsham Township, said on May 3 that the combined PFOA/PFOS level there was 10.8 ppt, well within the EPA limit of 70 ppt for those two chemicals. Aqua spokeswoman Donna Alston said all the company’s water systems in Bucks, Montgomery and Chester counties showed PFAS levels below the EPA’s threshold in the latest tests in March.

Although many utilities use the EPA’s PFOA and PFOS level as a benchmark, advocates say it’s too high to protect public health. For that reason, state scientists in New Jersey have recommended – and environmental officials are in the process of adopting – levels that are some five times lower than the federal standard.

In the EWG data, one of the bases, the former Willow Grove Naval Air Station at Horsham, had combined PFOA and PFAS contamination as high as 86,000 ppt, affecting 108 out of 161 wells on-base in testing during 2017, DoD data show. Public wells near the base had contamination of up to 1,000 ppt.

Other utility data show contamination well above the EPA’s health limit at Warminster and Warrington, two communities that have also been affected by PFAS chemicals from the military bases.

While utilities such as Horsham’s have largely removed PFAS from their systems since the samples were taken, the chemicals will still be present at some level because they don’t break down in the environment, said Bill Walker, vice president of EWG.

“When a water system is contaminated with PFAS, treatment will lower the concentration but not completely remove it. So the contamination is still there, just being treated at a cost to the water district and its customers,” Walker said.

EWG combined data from the three sources and presented it on the national map to show the widespread nature of the contamination rather than the severity of it, Walker said.

Nationally, there are now 610 sites in 43 states with PFAS contamination, the map shows. The last time the map was updated, in July 2018, there were 172 contaminated sites in 40 states. The two maps are not directly comparable because new data sources were added this time, but they show growing knowledge about a widespread national problem, EWG said.

EWG isn’t saying that every site on the map has water that’s unsafe to drink, but it does endorse research showing that PFOA and PFOS can harm human health at levels as low as 1 ppt, Walker said.

The chemicals, once used in consumer products like nonstick cookware and flame-retardant fabrics, are being increasingly regulated by states as more becomes known about their links to cancer and other health conditions including thyroid problems, low birth weights and elevated cholesterol.

In Pennsylvania, the Wolf administration said in February that it would begin to set its own health limits for PFOA and PFOS after the EPA declined to commit to doing so despite publishing an “Action Plan” that month to curb the chemicals.

Last September, Gov. Tom Wolf set up a panel of state officials to study the chemicals and recommend ways of curbing them. In April, the Department of Environmental Protection said it will begin sampling some 300 water systems around the state for six PFAS chemicals in a program that’s expected to take about a year.

In New Jersey, the state last year became the first in the country to adopt a tough standard for PFNA, a type of PFAS chemical, and is in the process of adopting low limits for PFOA and PFOS.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.