Pennsbury Manor whispers the noisy history of the Lenape people

Sound artist and Lenape descendant Nathan Young has installed noise and avant-garde music at William Penn’s historic estate.

Listen 3:13

Indigenous artist Nathan Young is a member of the Delaware tribe of Indians. He returned to his ancestral homeland to create an immersive sound installation on the grounds of Pennsbury Manor, colonial estate of William Penn. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Pennsbury Manor, William Penn’s 17th-century country estate near Levittown, wanted to bring the history of the Lenape people closer to the story of the site. So the historic house, administered by the Pennsylvania Historic and Museum Commission, asked artist and Lenape descendant Nathan Young to wire the estate with sound.

“This is my own personal opinion, but a lot of land acknowledgments seem to be just lip service,” Young said, referring to the increasingly commonplace gesture of formally stating the historic occupation by native people at public events.

“But here at Pennsbury Manor, by letting me do things like this and other things that Pennsbury has done for the recognized Delaware tribes — what they do matters,” he said. “It’s not just lip service. These are real, meaningful gestures.”

Pennsbury commissioned Young to create “nkwiluntàmën: I long for it; I am lonesome for it (such as the sound of a drum).” The title is a word in the original language of the Lenape people, pronounced KWEE-loo-NOMEN, and its approximate translation into English.

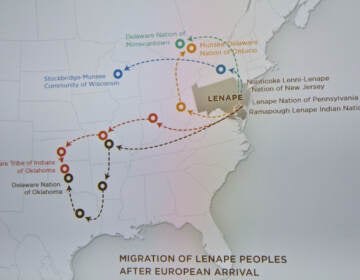

Young, based in Tulsa, Oklahoma, is a descendant of the Lenape people on his father’s side (his mother is Pawnee).

“Now we’re called the Delaware tribe of indians,” he said. “My tribe.”

Young installed speakers on several high-backed garden benches around the main house of the Pennsbury estate, each playing back music created for this piece by several composers. There are also large signs painted white, black, yellow, and red, that guide the visitor on a poetic journey.

“Follow me, walk the path. I have a drum,” Young wrote. “Where is the drum hide? I long for it. I’m lonesome for it. There is a trail ahead. Do you see it? I’m blind.”

Because the Delaware/Lenape language is considered dead — there is no longer anyone alive for whom it is their first language — Young relies on language databases to find out how his forebears would describe certain things.

Out of respect for his ancestors, and out of respect for the authenticity of his own lived experience as an artist, Young does not attempt to translate the English signage into something that would only vaguely resemble the real Lenape language. Instead, on the backs of the signs are abstract visualizations created by using the sounds of Lenape language to inform an image-generating computer code.

These abstractions, both visual and sonic, are Young’s response to a historic landscape steeped with a complicated history of colonists and native people.

“One of the voices that has been missing at Pennsbury Manor is a Lenape voice,” said site manager Doug Miller. “While this is a contemporary Lenape voice, it’s reminiscent of the time that the Lenape were here. His voice is echoing their voices that were forcibly removed here in the 1730s by the infamous Walking Purchase, which was propagated by William Penn’s sons about 20 years after Penn’s death.”

The Walking Purchase was a deal struck in 1737 with the Lenape people by Penn’s sons, in which the Lenape agreed to sell to the Penn family as much land as a man could walk in a day and a half. But Penn’s descendants tricked the tribe by hiring fast runners to mark the territory, instead of walkers, forcing the tribe to cede far more land than they had wished.

The buildings of Pennsbury Manor are recreations built in the 1930s of William Penn’s estate on 43 acres of land along the Delaware River, but only in the last couple years has it hosted rotating installations by contemporary artists.

Last year the estate showed “Dreams of Freedom,” an exhibition of quilts representing Harriet Tubman, created by the Sankofa Artisans Guild.

Miller called “nkwiluntàmën” a “signature” art event for Pennsbury. The professional historian who first started working at Pennsbury more than 25 years ago said Young’s installation is making him see the manor with new eyes.

“It’s given me a much greater sensitivity to the fact that I don’t know their history. The history that we think we know — we don’t,” he said. “The best thing to do is turn to the original source, which would be the federally recognized people who descend from Lenape and ask them to help us know, understand, and tell their history.”

Young, however, says he cannot speak on behalf of his ancestors. He points to the nuances of the Lenape language, in which the idea of “experiencing” something is expressed as “it penetrated me.”

“I didn’t experience it. It didn’t penetrate me,” said Young. “I’m trying to tell the story of all this, but I’ll let you know: I have no idea the pain they felt. I have no idea what it was like. None of us do. But I think we should contemplate.”

In “nkwiluntàmën,” the vehicle for that contemplation is sound. In his hometown of Tulsa, Young runs the record label Peyote Tapes, which releases new music, noise music, and avante-garde music as both digital and cassette tape releases. He tapped into his network of musicians to compose a Pennsbury playlist.

“These are just my friends and people that I do shows with, that visited Tulsa and we were able to collaborate,” Young said. “The music might become more challenging, and ultimately it ends with Native American noise music. There are a lot of Native American noise musicians now.”

One of the featured composers is Robbie Wing, who also helped Young pull the installation together. He collaborated with composer Rush Falknor to create a piece based on an electronically manipulated piano sample that he describes as an “eerie drone horror film idea.”

Wing’s pieceand all the sound pieces are played back very quietly from compression speakers built onto the backs of the garden benches. The sound is so subtle, a visitor walking past may not notice it at all. You have to actually sit on the bench to be able to hear it, and even then it’s almost a whisper.

“It doesn’t totally engulf you. You have to listen to the space that’s around you, the structure of the benches with what types of speakers are used,” Wing said. “We wanted to engage a lower frequency, so your body is engaged as well. There’s kind of a rumble to it.”

Visitors can engage with the “nkwiluntàmën” sounds on the benches, or on an app downloadable from a QR code, or some combination of the two. The app features a compass that guides visitors through the space, but the app itself proclaims not to care if visitors follow its directions.

The recorded music interacts with the sounds of wind, honking geese, a nearby athletic field, places overhead, and the rumble of international cargo ships that churn past on the river not 100 yards from the estate grounds.

Young wants people to explore the space, and use the music to sit more deeply with the past and the present of the Lenape people.

“We have a saying in Oklahoma, where there are 39 Federally recognized tribes: ‘Our songs come from the wind,’” Young said. “The sound of water, the sound of birds, the sound of rustling — it only adds to it. Nothing’s in opposition here. It’s just a story.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.