PennDOT archaeologists uncover historic Dyottville Glass Works

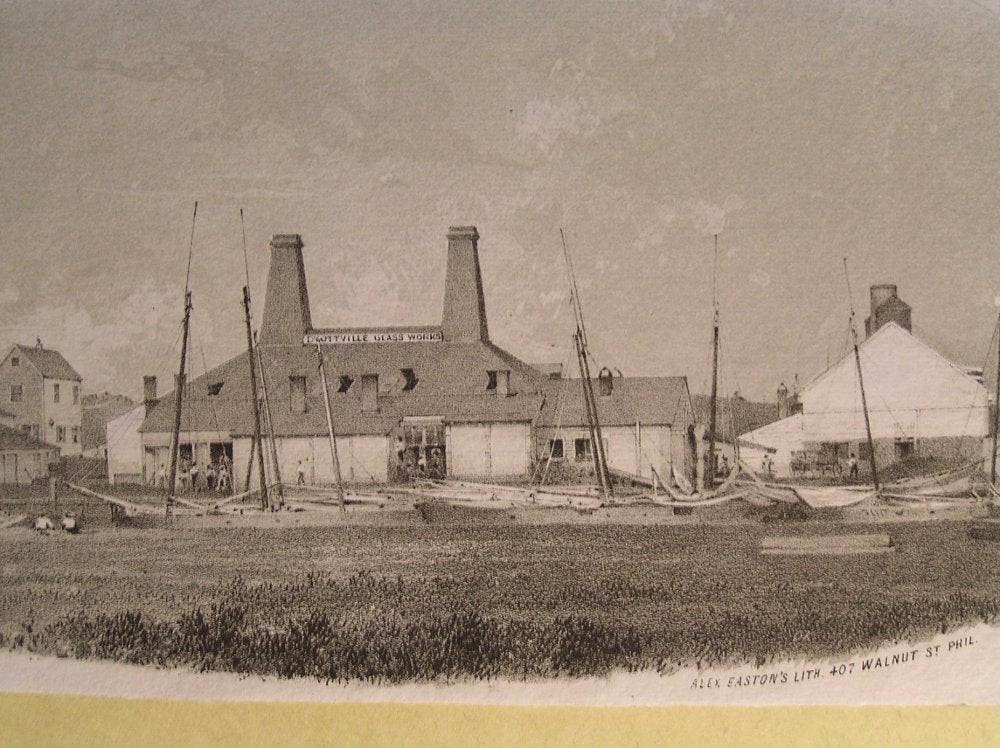

Beneath asphalt, railroad lines and cobblestones, archaeologists working for PennDOT have unearthed the schist and brick foundations of the Dyottville Glass Works ovens.

This is where workers employed by Thomas W. Dyott in the 1830s tempered the bottles for the bootblack and patent medicines he sold around the country. The roughly 300 people employed by the glass works in 1830 also lived, farmed, worshipped and attended school within the 300-acre complex that the self-proclaimed Dr. Dyott assembled in hopes of creating his own, self-sufficient society.

Senior URS Archaeologist Doug Mooney and his team are unearthing, photographing, mapping and cataloging the site for PennDOT as part of the agency’s rebuilding of I-95.

“They have to map all of that, and document it, because it is going to be destroyed,” said Cathy Spohn, a PennDOT cultural resource professional. A street will go on top, and utilities through the site, said Project Manager Elaine Elbich, but not before the artifacts are collected and cataloged and the ruins are photographed, mapped, and three-dimensional images are made.

Archaeologist Mooney tells the story of Dyottville Glass Works

Dyott wasn’t the first man to make glass here, and he ran the factory for less than a decade of the 150-plus years that glass was manufactured in this part of Fishtown and Kensington.

But his work in the 1830s was the most historically significant of all that was done there.

“This was the preeminent glass works in the city,” said Spohn.

But Spohn and Mooney agree that what makes the the Dyottville site so historically valuable is the combination of the industrial history of the glass works and the social history of the Dyottsville community that surrounded it.

PlanPhilly is not publishing the exact location of the dig, at the request of PennDOT. Officials and archaeologists alike are concerned that people interested in Dyottsville bottles – which are valuable to collectors – might come looking for them before all is recorded and cataloged.

Whole bottles have not been found, Mooney said. These are the ruins of the annealing ovens, where hot bottles were brought to slowly reduce their temperature, preventing the cracking that happens when hot glass is cooled quickly. Bottles that made it out whole were removed from the area in preparation for sale, he said.

“What you actually find are bits and pieces, and also a lot of things that they would use in the manufacturing of glass,” Spohn said.

The bottom few boards of a simple shed that stored sand – the main ingredient in glass – was discovered, with sand still in it.

“The site is extraordinarily well preserved,” Mooney said.

The team has also found pieces of glass canes and witch balls – decorative glass balls that some thought warded off evil. These are items workers most likely made on their own time, for personal use or as gifts, Spohn said.

The site itself is largely a maze of what look like foundations for the tiniest row houses ever. They are actually the foundations of the annealing ovens and some interior and exterior walls. Brick walkways are visible, too. One structure, however, is different from the rest. An arched, brick passageway leads to an iron door that opens into an oven. Mooney would love to open the door, and explore what is on the other side. But he can’t. The parcel next door is privately owned, and not part of the I-95 project.

The oven door, and other structures

Some of the structures date back further than glass manufacturing. Some are linked to a calico printing works and bleach yard established by an in-law of Martha Washington in the spring of 1774. It was the first calico printing works in Pennsylvania, and Martha Washington commissioned owner John Hewson to produce some fabric for her husband, George. Other pieces are from an earlier glass works, called alternatively the Philadelphia or Kensington Glass Works, which Dyott purchased. Mostly, the structures were retooled for or incorporated into the business that followed, Mooney said.

Dyott, a self-proclaimed doctor, immigrated to Philadelphia from England in the late 18th or early 19th century. He ran a profitable, nation-wide bootblack and patent medicine business, and Mooney’s research turned up old city directory references to a Dyott-owned patent medicine warehouse at 57 South Second Street in 1807 and a medical dispensary at 116 North Second Street in 1809. By that year, “he had at least 14 agents in 12 towns and cities in seven states,” according to Mooney. Through those agents, and newspaper advertisements, he became a nationally recognized medical figure.

In the 1820s, Dyott was looking to expand again. He began buying up glass works in Fishtown and Kensington.

He later established the church, the school, the houses and the farms and the rules that governed his worker’s lives, Mooney said.

“A few blocks away, he built 40 houses for married workers,” Mooney said. Unmarried men, women and children lived on site here. There was a large farm to the north where they had a dairy farm and grew all the food they needed.”

There was also hospital, athletic fields and a pot shop.

Dyott also established his own bank. “He printed money with his picture on the money,” Spohn said.

That bank went bust in the nation-wide panic of 1837, Mooney said. “He had overextended himself,” he said. “There was a run on the bank, and he was not able to pay back his creditors.”

Dyottsville glass closed when Dyott, convicted of fraud, went to Eastern State Penitentiary. He served 15 months before being released for good behavior.

“Over time, he re-entered the drug industry, and was able to reclaim most of the money he lost,” Mooney said.

His former factory was idle for a few years, but another glass maker reopened it in 1842, tearing down the structures and rebuilding something larger on the same site. Internal modifications were made again in 1880, and glass continued to be made through at least 1895, Mooney said.

“All four phases of that construction are represented in the ruins that we have here preserved on site,” Mooney said.

When the factory-related digging is finished, the archaeologists will go deeper. They expect to find Native American artifacts, thousands of years old, beneath the glass works.

Much of what is found is expected to go on public display this fall, during what will be the third annual exhibit and lecture on key discoveries made during the federally mandated dig along the highway’s new route.

Reach the reporter at kgates@planphilly.com

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.