SugarHouse archaeology work is finished

Casino interest has unearthed thousands of artifacts; Sand Hill Indians want to examine the finds immediately but Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission says it has more work to do before that can happen.

Dec. 17, 2009

By Kellie Patrick Gates

For PlanPhilly

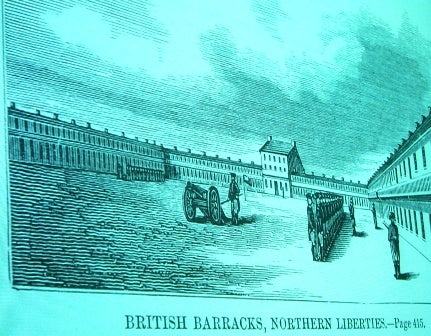

SugarHouse Casino says it has finished its archaeology field work without finding the remains of a British Revolutionary War fort that was once located on the site.

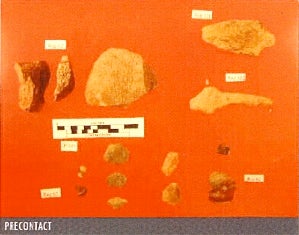

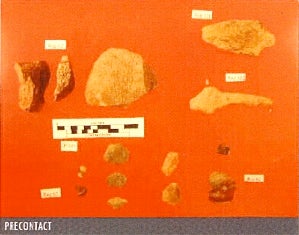

But thousands of artifacts were found at the North Delaware Avenue site, including tools used by Native Americans 3,500 to 4,000 years ago. And these will likely be examined by the New Jersey Sand Hill Band of Lenape and Cherokee Indians, based in Montague, Sussex County.

“First, they want to determine if the artifacts are Lenape,” said Laura Zucker, spokeswoman for the tribe. “Then the next step is to sit down, probably over lunch, and talk with everyone involved … in an air of cooperation.” Zucker, who is not Native American, said the Sand Hills are “very grateful the artifacts are being safely stored and protected.”

SugarHouse spokeswoman Leigh Whitaker said the casino’s archaeology team finished digging last week, but it will take a couple of months for them to photograph and catalogue the thousands of artifacts discovered. Not all of the artifacts are Native American. While most artifacts are shards, some complete tools, 12 pieces of intact 18th- and 19th-century pottery and one 1852 American gold coin – denomination $1 – were also found. The report will go to the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, and if the Commission agrees that SugarHouse has met the terms of a memorandum of understanding signed last month, SugarHouse will be officially done with the dig.

The artifacts themselves will also go to the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, and will be housed in the state museum’s collection. Mark Shaffer, an archaeologist with the Commission’s Bureau for Historic Preservation, said the PHMC received a letter from the Sand Hills last week. They want to examine “artifacts and bones” that have been discovered.

None of the archaeological reports reviewed by PlanPhilly indicate the presence of human remains. Shaffer says that no bone fragments or items affiliated with burial were found. But, he said, a response telling the Sand Hills that they can make arrangements to view the artifacts with the curators has been written.

“It will be awhile before they are processed,” he said. “For every day you spend digging, you spend two or three in the lab analyzing and writing it up.”

Zucker, the Sand Hill spokeswoman, said they want to see whatever has been found, human remains or not. The tribe will be pleased to get a positive response, from PHMC, she said, but they do not want to wait several months. “It can be done while they are still cataloguing and photographing,” she said. If the PHMC doesn’t have the artifacts yet, she said, the tribe will try to make arrangements with the archaeologists. “You don’t leave a tribe waiting to see what would possibly be the artifacts of their ancestors.”

Shaffer said a Philadelphia organization has contacted the PHMC about interpreting the artifacts that had been found for city residents and visitors. The Philadelphia Multicultural Affairs Congress, a division of the convention and visitors bureau, has been in touch with him for some time, he said. The person from the Congress who contacted Shaffer, executive director Tanya Hall, could not be reached for comment. But Shaffer said she has told him that explaining what was found at the site could help promote Philadelphia’s history.

Hall told Shaffer that she was not necessarily interested in displaying the artifacts. But the state museum does sometimes make a loan of physical artifacts to groups that wish to display them, Shaffer said. The group first has to show that they have the appropriate facilities to keep the items preserved and safe.

Shaffer said that the preponderance of the artifacts found are shards of stone that most people wouldn’t recognize as anything special. But the Native American tools have been tentatively dated to be as much as 4,000 years old, based on the ages of similar artifacts found at other sites in the mid-Atlantic region. Archaeologists will learn more, he said, when they do carbon dating on the charcoal found in the one fire pit discovered at the site.

Findings like this aren’t rare, generally speaking, he said, but it is highly unusual to find something so old within the Philadelphia city limits, and that makes this significant.

Zucker was pleased to hear about the Philadelphia Multicultural Affairs Congress’ interest, and said the Sandhill would be happy to help with artifact interpretation.

The archaeology work began at the Fishtown site more than two years ago. Back then, SugarHouse was seeking a federal permit from the Army Corps of Engineers, and federal law required a historic review. In such cases, the Army Corps works with a team of advisors who are called consulting parties. They are also advised by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.

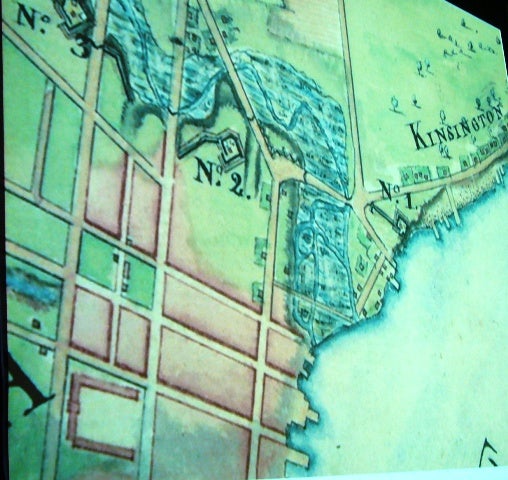

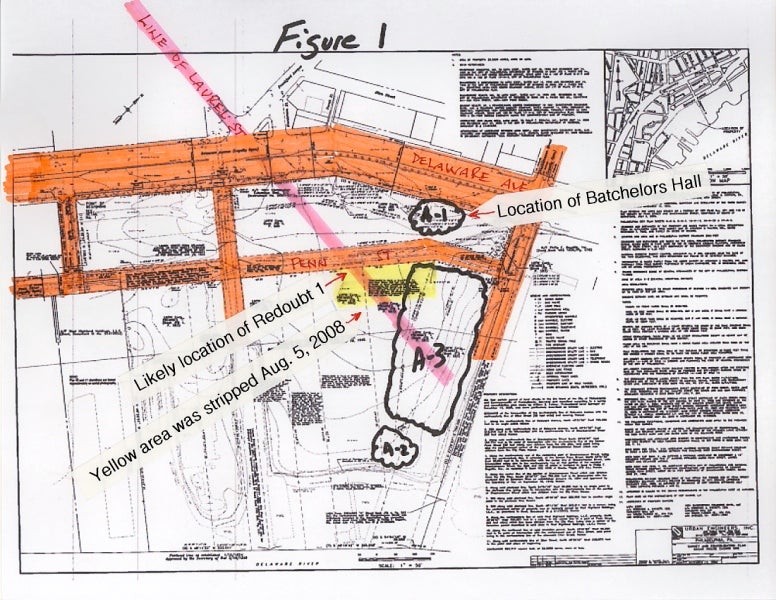

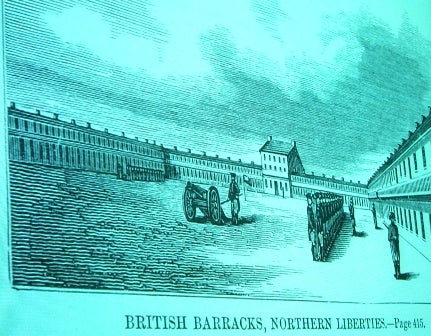

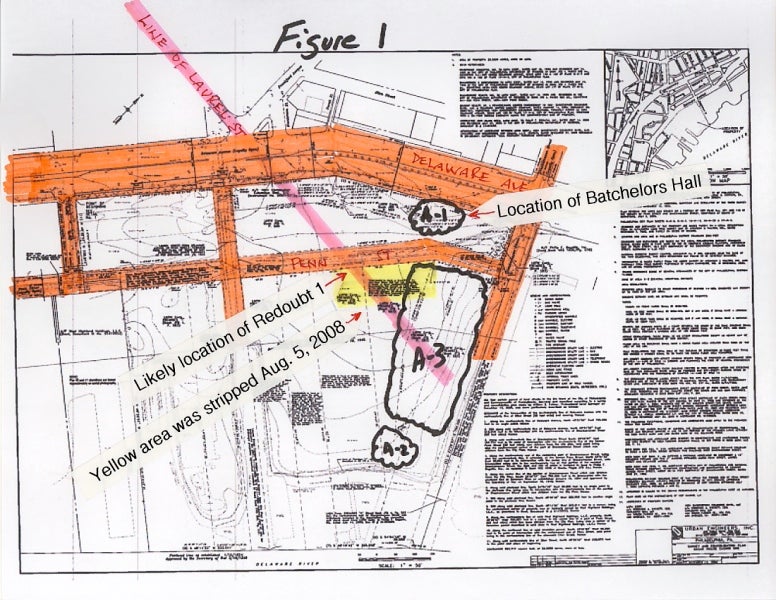

Often, the process was contentious, with the consulting parties pushing for SugarHouse and its archaeology contractor, A.D. Marble, to do more work. SugarHouse always stood by Marble’s expertise. But the consulting parties often questioned it – as was the case when local historian Torben Jenk produced reams of evidence that the British Fort, Redoubt No. 1, and a colonial club called Batchelor’s Hall, had been located on the site. (Although never asked to do so by the state or Army Corps, SugarHouse instructed Marble to search for Batchelor’s Hall where Jenk specified. Remnants of a building were found, and Jenk believes they were part of Batchelor’s Hall. Marble, SugarHouse, the Corps and the Commission do not accept that view.

Earlier this year, SugarHouse modified its building plan and told the Corps it no longer needed a permit. The federal historical review process ended. SugarHouse volunteered to finish the archaeology according to the PHMC’s recommendations, anyway, Shaffer said. If they hadn’t, they might have been forced to under state law, he said, because the project also needs a Department of Environmental Protection permit.

At an April gaming control board hearing where SugarHouse testified that it needed a license extension, SugarHouse chief investor Neil Bluhm said he had been told that SugarHouse has spent more on archaeology than any other private development in the city, and he was proud of that.

The British fort was one of the things SugarHouse was looking for during the last part of the dig, which was completed last week, after utility lines that run beneath Penn Street were turned off, Whitaker said. Jenk and other historians and archaeologists including Doug Mooney, president of the Philadelphia Archaeological Forum, were hopeful that some evidence of the fort would be preserved there.

“The archaeologists found that it was highly disturbed. Anything of historical significance was gone a long, long time ago,” Whitaker said.

Jenk said he is not convinced that fort remnants could not have been found elsewhere on the site had the dig proceeded differently. For one thing, Jenk said, the maps used by A.D. Marble were not accurate. For another, he said, some digging was done before Marble knew the fort had been located there.

Jenk and other consulting parties made similar complaints through the entire historic review process. SugarHouse has always stood by A.D. Marble, and was confident that Marble’s maps were correct.

Mooney said that even though no remains of the fort were found, the work done by Jenk and the other historians was extremely valuable. “As far as I know, there hadn’t been a great deal of work done focusing on the British fortification of Philadelphia prior to this. It was really previously not understood.”

Jenk feels that his work was mostly ignored during the historic review process, and that was frustrating, he said.

But he has been giving talks about the fort around town, and he continues to get invitations to do so. He plans to write up all the information he has on the fort, including links to “the real map,” he said, so that anyone interested will have the reference.

Jenk and another local historian, Ken Milano, are also planning to compile their discoveries on all of Point Pleasant – not just the SugarHouse site, but the land around it.

Like Jenk, the Philadelphia Archaeological Forum was not very happy with the way the historical review process proceeded. “Things should have happened in a lot more open, transparent manner and without the acrimony and struggle that did arise.”

But Mooney believes the pushing the consulting parties did resulted in more artifacts being found. And he is pleased that SugarHouse and Marble continued the dig after the federal process ended.

“Ultimately, (the Forum’s) goal in all of this was to make sure the archaeological resources got the treatment and study they deserve,” he said. “That is what happened. In the end, the history wins.”

Contact the reporter at kelliespatrick@gmail.com

ON THE WEB:

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.