Pebbles point to ancient rivers on Mars, Penn study finds

Listen

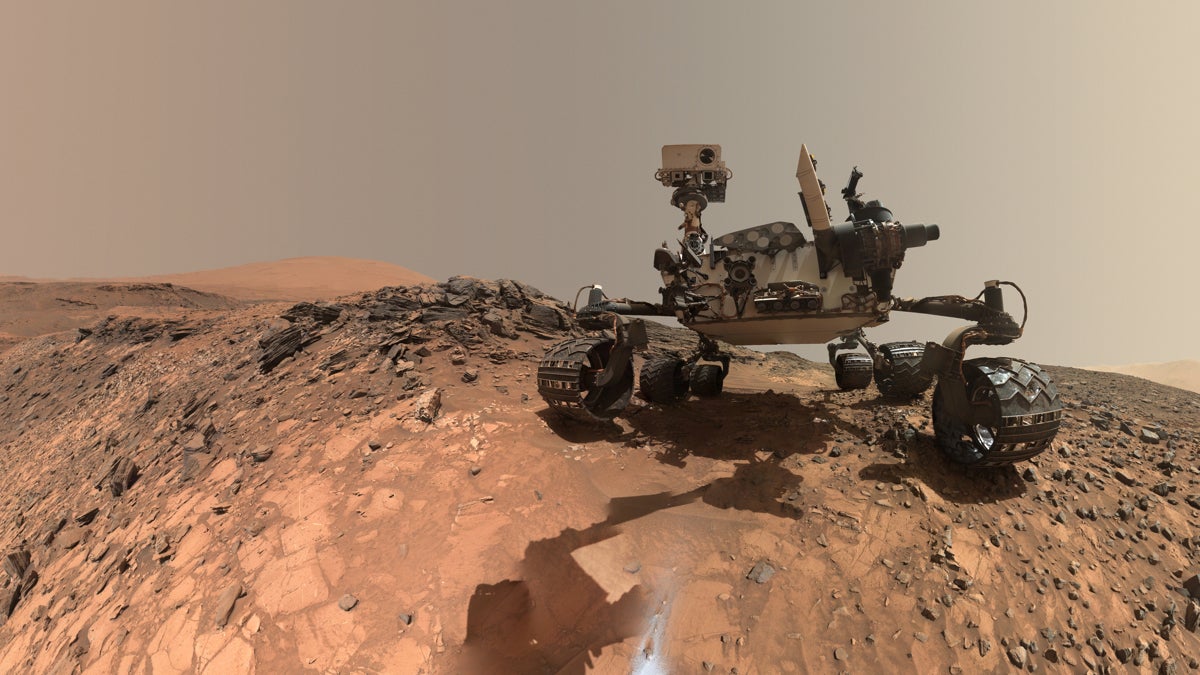

Mars rover Curiosity takes a self portrait on lower Mount Sharp in Gale Crater. Researchers analyzed images of pebbles taken by the rover and found some of the rocks had once traveled long distances in a river. (Image courtesy of NASA)

How much can the shape of a rock tell you? According to researchers at the University of Pennsylvania, quite a lot. A new analysis of Martian pebbles suggests that more than three billion years ago, the red planet was home to lengthy rivers.

Penn geophysicist Doug Jerolmack and his team looked at snapshots of pebbles captured by the Mars Curiosity rover. By applying some math, they calculated how far those rounded stones had traveled using just the rock’s contours as displayed in the two-dimensional picture. The estimate? About 30 miles.

“That says it was at least warm enough and wet enough so that water could course over the surface of Mars for a very long time without freezing,” said Jerolmack, who is the senior author of the study.

Rounded pebbles photographed on the surface of Mars by the Curiosity rover indicate that Mars once had an extensive river system, according to researchers at the University of Pennsylvania. (Image courtesy of NASA)

Rounded pebbles photographed on the surface of Mars by the Curiosity rover indicate that Mars once had an extensive river system, according to researchers at the University of Pennsylvania. (Image courtesy of NASA)

The math necessary for the calculations didn’t exist even a decade ago. Gábor Domokos, a professor of mechanics at the Budapest University of Technology and Economics and a co-author of the study, said the equations used to model a pebble’s shape over time required the solution to the Poincaré conjecture.

“This was one of the great standing questions in math,” he said. “They didn’t care about pebbles, but this is how things evolve in science.”

The shape-based premise works because when rocks bang into each other, they do so predictably: the points that protrude the most will be worn down the fastest. The researchers first find out how much mass has been lost to erosion. Then they’re able to derive an estimate of the rocks’ travel distance.

The team tested its predictions in the field, measuring thousands of stones at various locations in rivers in Puerto Rico and later in New Mexico. The theory was a surprisingly good fit, Jerolmack said.

The findings, which were published Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications, jibe with other recent discoveries about water on the red planet. Last week, NASA’s Curiosity team reported that Mars once stored water in lakes. And last month, the agency revealed that water likely exists currently as part of a salty brine solution that is liquid during certain parts of the year.

In addition to Mars, the team’s method of determining a rock’s journey could also help find gold or iron deposits on Earth, Jerolmack said.

But the just as the mathematicians who solved the Poincaré Conjecture never imagined their work would end up being used to trace the migration of pebbles on Mars, Jerolmack is reluctant to subscribe the group’s discovery to a set number of applications.

“I find this kind of thing beautiful that we can connect the mathematics to a geophysical problem,” he said. “In the world of science and engineering, when you put an idea into the world, you never know who’s going to respond to it.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.