Patrolling with West Frankford Town Watch

Mike Mawson smells something.

It’s past midnight on Comly Street near Bustleton in Mayfair. The sun went down hours ago, but forgot to take this sticky July heat with it. Mawson is riding shotgun in the sensible four-door sedan that his partner Phil Pappas drives. The West Frankford Town Watch patrol was circling around to head back south of Cheltenham Avenue to drive the streets of its namesake neighborhood when Mawson caught a whiff of something off in the still nighttime air.

“It smells like something is burning,” confirms soft-featured Pappas, 53, sitting upright with two hands on the steering wheel and dressed with purpose in matching earthtones. “I’ll pull over.”

Mawson, 41, flips open the passenger side door and, with the help of his right hand pulling from the car roof, peels his body from the low seat and lumbers down the narrow drive that leads to the kind of wide, back alleyway that stone-faced Mayfair rowhomes share the neighborhood over.

SEPTA has a well-lit bus depot that sits right at the triangle created by Comly and Penn streets meeting at Bustleton, but here, just a block and a half down Comly, two yellow street lamps strain to compete with the dark black night.

Get involved

To donate, participate or learn more about the West Frankford Town Watch:

Contact President Mike Mawson

By email: westfrankford@yahoo.com

By phone: 267-628-7712

By mail: 4724 Darrah Street, 19124

Pappas is keeping his eyes on Mawson, the town watch president who now has his flashlight unsheathed and is poking around bushes and sniffing around quiet and well-kept front lawns, but it’s clear he’s losing the scent. Mawson seems to agree as he piles back into the car. Pappas pulls away from the curb, turns the corner and navigates the narrow back alleyway, the two focusing on trying to find the faint smell of smoke that seemed to hang but was now dissipating.

“It smells like it was coming from around here, but I think it’s going away,” Pappas says, while Mawson cranes his neck out the window like a hound dog.

Sensing a fire was not on the loose, Pappas continued down the final leg of the narrow L that made this hardly navigable alleyway, dropping harshly and loudly off the curb back onto Comly.

The first crisis of the night appeared to be averted, but the man driving the car suddenly has his ears tuned to something else.

“Do you hear that?” Pappas asks, though it’s not clear to whom.

TOWN WATCHING ACROSS THE NORTHEAST

The pair are perhaps the most dedicated of the nine active members of West Frankford Town Watch, a decidedly specific title for a group that is less than concerned about the exactness of its patrolling boundaries. Their weekly ritual — haunting every Friday night a rolling corridor that hovers around Frankford and Mayfair that is reflective of its membership — is one duplicated across the city, particularly the Northeast.

Today there are more than 720 certified town watch groups and 20,000 trained members in the city, according to Town Watch Integrated Services, an agency of the City of Philadelphia. Nearly a dozen town watch groups walk and drive their communities in the Northeast, but, citywide, there’s no mistake that many, if not most, of those groups are less than active.

Yet, the latest budget cut conversations include trims to police overtime budgets, a fast means to engender groans from a city population often obstinate in its defense of law enforcement dollars. Violent crime is down from last year — and has been mostly trending down nationwide for years — but the conversation around community policing doesn’t seem to go away.

“People want to know more is being done to keep our homes safe,” Mawson says.

In Mayfair, resident John Vearling has been on something of a crusade the past year, trying to build his own force of resident watchdogs. Fox Chase, Tacony, Holmesburg and other neighborhoods have seen their town watch groups wax and wane in recent years.

The difference in Frankford, or, to be more specific, with the West Frankford group, is that they’ve stayed active for so long — longer than any other group in the Northeast and among the most active citywide, Mawson says.

First founded in the 1980s by lawyer John Beggin, the West Frankford Town Watch fell into inactivity by the mid-1990s, but Mawson helped revive it around 2000, when he scored permission to put their radio repeater on top of Frankford High School in exchange for truancy enforcement.

That means their radio communication was more consistent, and the group has been out on the streets ever since, Mawson says.

That’s important, he adds, because, as anyone in the Northeast will tell you, the part of the city Mawson’s teams patrol could use the help.

PATROLLING

They’re a portly pair, as un-intimidating as they are confident.

Mawson is a big man with a tiny mustache, clear blue eyes and long curly hair, a UPS driver whose work hours make him a creature of the night. He keeps his shirt untucked and makes the final call on directions to go and places to stop.

Pappas is quieter, more reserved. He keeps a radio strapped across his chest, with the receiver dangling from his shoulder. His lightly colored beard is neatly trimmed. He remains deferential to Mawson, but he seems no less sure when he pops out of the car himself.

That car hasn’t gone very far.

Fifteen minutes after investigating the smell-that-was, Mawson has gone to the front of the small apartment complex that sits just south of the Speedy Mart at that same triangle by Comly and Bustleton. He’s ringing what he thinks is the doorbell of a tenant who has what sounds like a fire alarm going off, and Pappas is standing outside the car by the open window from which that sound is being emitted, more faint, yellow lights giving Pappas the shadowed appearance of greater size than his five foot seven inch-frame would otherwise.

It’s a tiny sound. Tiny enough that it ends up being just an alarm clock, and the two return to the car again, apologizing for the lack of excitement.

But that’s just the point. The importance of town watch groups comes with their impotence.

THE VALUE OF TOWN WATCH GROUPS

Town watch groups travel in pairs, with nothing that gives them any authority beyond a walkie-talkie, fluorescent vest and flashlight. They’re not meant to intervene in crimes, nor should they directly approach or otherwise interfere with anything that police officers would — never encouraged to be actors in anyway.

Town watch members receive a few hours of training from a city agency, taught by community specialists — like Chad Enos, who handles Northeast town watch groups — and go through basic protocols and safety tips at open meetings that are held at homes or churches and just might end in juice and cookies.

Vigilantes or crusaders need not apply, though that spirit seems to run through those interested in volunteering their Friday nights.

“There is this small taste of the police work, without the commitment and all the paperwork,” Mawson says. “Or the physical or age requirements.”

Instead, Mawson, Pappas and the rest of their members ideally worry about problems when they remain tiny — the faint smell of smoke, the beeping noise in the distance. Town watch members are first responders before anyone ever calls the first responders.

Philadelphia police officers probably shouldn’t spend their time circling quiet blocks chasing a smell that has as good a chance of being the residue of a BBQ as it does the start of a five-alarm blaze, but the West Frankford Town Watch can.

If a situation escalates, Mawson and crew serve as an alert, responsive cadre of nosy neighbors — a characterization that means they “annoy some cops, but most really appreciate the help,” he says.

THE PATROL

On this night, the West Frankford Town Watch is, interestingly enough, headquartered in Mayfair, near the corner of Farnsworth and Hellerman streets.

When the game is getting as many participating members as you can to reduce burnout and increase coverage, Mawson says, “with town watch, your boundaries go as far as your members live.”

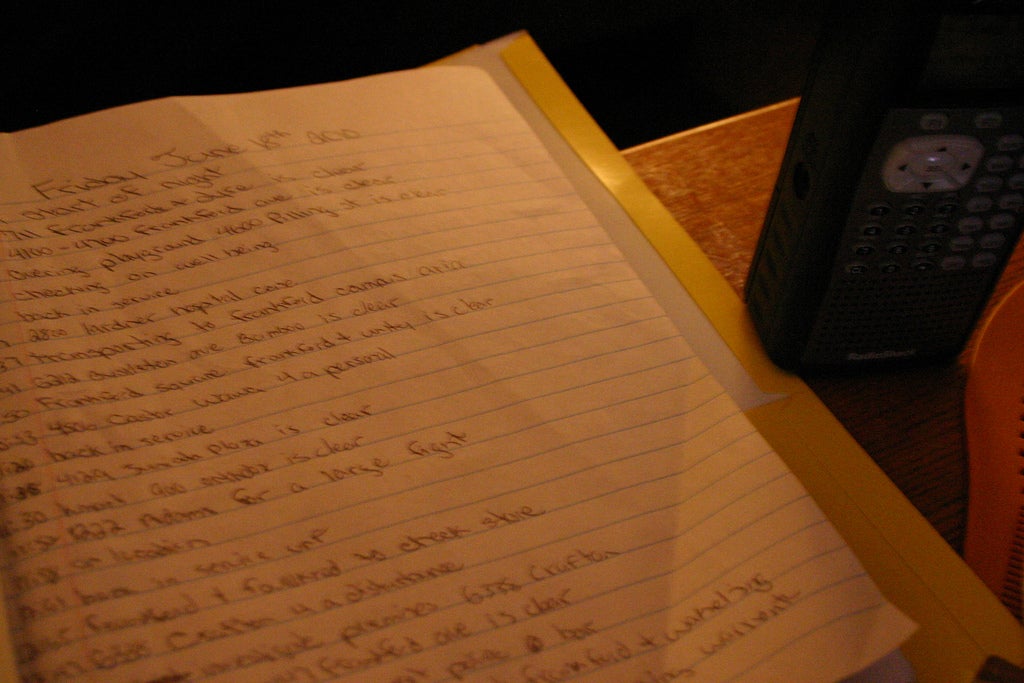

So that’s why tonight, like on many Friday nights, a scanner, walkie talkie and supply of Diet Coke are all within the reach of Gina Hriczo inside her second-floor rowhome apartment.

Hriczo, 30, will keep the patrolling log, offer general support and, ultimately, serve as lifeline and contact if anything serious were to happen. In between radio calls, she instant messages on Facebook and waits for her boyfriend, who is also a town watch member, to come home from his job with SEPTA.

Mawson and Pappas — the only patrol West Frankford has tonight — will make a dozen stops, including two at Wawas for snacks and bathroom breaks, circle back twice and cover more than 30 miles from nightfall around 9 p.m. to nearly 3 a.m., when the bars are closed and most of their patrons have found their way home.

On this night, the pair saw police in action only twice — once handling a fight on a SEPTA bus along Wyoming Avenue across from the Cancer Treatment Center of America and again, stationed on the angular sidewalk expanse outside the Thriftway at Frankford and Pratt Streets waiting last call at a series of trouble bars around the Frankford Transportation Center corridor.

“It was quiet tonight. Quiet is good,” Mawson says. “But a little action can make the night go quicker.”

WHO GETS INVOLVED WITH TOWN WATCH?

If there is a town watch group anywhere that isn’t in a perpetual donation and membership drive, let them speak now.

On weekend days, the West Frankford Town Watch can often be found asking for change along Harbison Avenue near Roosevelt Boulevard, seeking the donations to pay for more flashlights, batteries, gas money and other equipment to supplement the radios and vests that the city provides by way of the Greater Urban Affairs Council. Every Monday, Mawson starts calling his members to see who will be available the coming weekend.

“Money helps,” Mawson says. “But we could always use more people. We’d love to have more patrols, cover more ground and get out more nights.”

Most neighborhoods are either too safe to elicit fear enough in their civic-minded residents to make them town watch members or too overrun with crime to have many residents left who think their neighborhood is worth saving. Neighborhoods in transition don’t stay like that for very long, so town watches are tricky things to steward.

Mawson is a 1987 graduate of Frankford High School. He still lives at Darrah and Foulkrod streets. But most of his members don’t live in Frankford.

Pappas remains a Mayfair kid, a 1974 alumnus of Lincoln High School — a school Hriczo, a Feltonville native, also graduated from, 24 years later.

Mawson is the kind of guy who went out and bought a $700 police scanner around 2004 when the Philadelphia department had just dropped its analog radio signal and went digital.

“Back then, pretty much the only people buying the new scanners were truckers and drug dealers,” Mawson says, before pausing, holding in a laugh that tosses back his hair with a shake of his ruddy cheeks. “And me.”

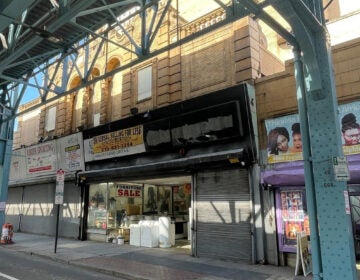

Pappas characterizes himself as generally “civic and politically minded.” Formerly the 62nd Republican ward leader, Pappas talks about what happened to Frankford — from prime shopping district to blight.

“I wanted to find a way to make the place I grew up around better,” he says.

Hriczo is bubbly, sarcastic and cutting. She has short black hair, dresses comfortably and, on this night, nearly never leaves her computer chair. She has a plasma screen TV nearly the size of her living room wall that has a Will Ferrell movie on low. She first got into community policing as a teenager hanging around the Feltonville Rec Center.

“I figured working with town watch was better than getting chased by the police,” she teases. “Though I still got into some trouble.”

And Hriczo is a teaser. On this night, she won’t leave Mawson alone — picking on him for his weight and his age and anything else she can. But it’s not mean spirited. Mawson parries back, but he’s no match for how quickly and consistently Hriczo digs.

If hyperbole were any less a crime, one might describe them as acting like family.

Around 1:30 a.m., Pappas pulls into Wawa for the second break of another in a long line of Friday nights given to a cause no more than few dozen people know about. Mawson buys a couple coffees and they bring one back to base — to Hriczo, who sleepily comes out to the street to get it before the last hour of the night’s patrol.

If every man has to give himself to something, then the act of two single men — Pappas lives with his ailing mother and Mawson lives alone — bringing coffee back to their makeshift town watch headquarters to make it through one last Friday night sure seems to be evidence enough that they’ve found where they’ll be giving themselves.

CONCLUSION

Mawson and crew have their stories.

They talk about the nuisance bar they patrolled, reported to police and followed to zoning meetings until it was shut down. They’ve helped drag hoses for firemen and lit up with spotlights dark corners of parks and schools to break up groups of kids when things looked like they might get out of hand. Mawson carries crime scene tape, tools and extra equipment. They are, in the word he keeps using, “prepared.”

“We make sure to get out of the car, so we get to know the people. The beat officers know us. We sometimes beat the police to crimes or help out at routine stops, like burglary alarms that are accidentally tripped. We direct traffic or do whatever else will get the officers back to the paperwork so they can get back to patrolling.” Mawson says, noting that most town watches are more talk than action. “We do a lot of things.”

It’s hard to measure the impact West Frankford Town Watch has had — or any town watch for that matter. What is the value of having a group of residents care enough about their community that they pour their time and energy into it without end or thanks?

“I’m not sure,” Pappas says quietly, while idling in the parking lot of a packed Brazilian dance club while Mawson talks to some patrons standing outside. “But I’m not sure I’d want to see what would happen if we stopped.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.