Online learning can open doors for kids in juvenile jails

Marquell Brown is one of a growing number of people in Illinois who have earned a high school diploma from School District 428, run by the department of juvenile justice.

Students have access to hundreds of courses while they are in Illinois’ juvenile justice facilities, but they tend to focus on math, language arts, social studies and science. (Tara Garcia Mathewson/ The Hechinger Report)

This story originally appeared on The Hechinger Report.

—

By Marquell Brown’s count, he has been locked up “roughly 42 times” since 2009. He has been in state and county jails for a range of crimes, including nonviolent offenses like trespassing as well as more serious ones. In February, Brown had been out for six months and he called it a record.

Brown, now 21, vows he’s not going back to jail. “I’m using my mind,” he said.

Brown is one of a growing number of young people in Illinois who have earned a high school diploma from School District 428, run by the state’s department of juvenile justice. At the same time that the state has been locking up fewer kids each year — “right-sizing” its juvenile justice population, according to an official strategic plan— District 428 has been awarding more credits and handing out more diplomas to those incarcerated.

According to state data, the number of young people in state juvenile justice facilities dropped from 901 at the end of 2012 to 386 in 2017. That’s a more precipitous decline than seen in the national numbers, which are moving in the same direction. (In 2016, 45,567 young people were held in facilities nationwide, down 20 percent from 2012.) In Illinois, District 428 awarded 73 high school diplomas in 2017, up from 65 in 2013 when there were twice as many juveniles in the system and their average stay was longer.

Sophia Jones-Redmond, superintendent of the district, which serves students from ages 13 to 21, said that a blended-learning model has been a major factor in this success. While teachers still provide some instruction, students also get to take classes online, and they have the option of moving through the coursework at a faster pace than traditional school schedules allow.

“The self-paced schedule has made a huge difference in the number of kids obtaining credits,” Jones-Redmond said. “Once they start, they really want to keep going.”

The online coursework is designed by the education company Pearson. Students technically have access to hundreds of courses, but Jones-Redmond said the district focuses on math, language arts, social studies, and science. Students are scheduled to spend five hours each day in school and much of that time is spent on computers, working through the courses they need to graduate. Teachers are always nearby, to help students one-on-one or to guide small groups. Jones-Redmond advocates a no-computer policy on Wednesdays when traditional teaching takes center stage and students take a break from their online work.

While online-only programs have come under fire for deprioritizing classroom relationships and providing too little instructional support for students, blended programs have been seen as able to strike an ideal balance. In 2014, an Illinois Department of Juvenile Justice remedial plan, created as part of a settlement agreement following a 2012 lawsuit against the department, specifically called for a blended-learning model to resolve inadequate educational opportunities in the system. Its implementation has coincided with the rapid rise in course completions and diplomas awarded.

A 2015 survey by the Council of State Governments Justice Center found that only 13 states provided educational services for kids inside juvenile justice facilities that were comparable to those provided for kids outside of them. Just eight states provided both comparable educational and comparable vocational services.

And the more students to whom District 428 can award a diploma, the more lives Jones-Redmond considers saved.

“This is such an exit ticket to a better life and a better future for these young women and young men,” Jones-Redmond said.

Nationally, researchers have found that people are less likely to end up back in the criminal justice system if they meet educational milestones and that adults with higher levels of education have better employment rates, less incidence of homelessness and better health outcomes.

But a 2015 survey by the Council of State Governments Justice Center found that only 13 states provided educational services for kids inside juvenile justice facilities that were comparable to those provided for kids outside of them. Just eight states provided both comparable educational and comparable vocational services, the survey found.

Illinois’ effort to bring online learning to juvenile justice facility classrooms is rare nationwide. Lynette Tannis, the author of a book about educating incarcerated youth and an adjunct professor at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Education, said she sees more examples of what shouldn’t be happening in juvenile justice facilities than examples to celebrate.

Students in Illinois’ juvenile justice facilities now take courses online in a blended learning program that has led to significant increases in the number of credits students earn while detained. (

In Illinois, Marquell Brown got a firsthand look at the improvements made from 2009 to 2017. Before 2012, he said, classes were routinely canceled, and when he did have them, he often learned information he had already covered in his neighborhood school. He was among the many young people who filed grievances about the lack of quality instruction, complaints that eventually contributed to the lawsuit.

“A lot of people want to go and learn and do something with their time, so when they get out, they’ll say ‘I got credit from here,’ ” Brown said. “Keep it going in the real world.”

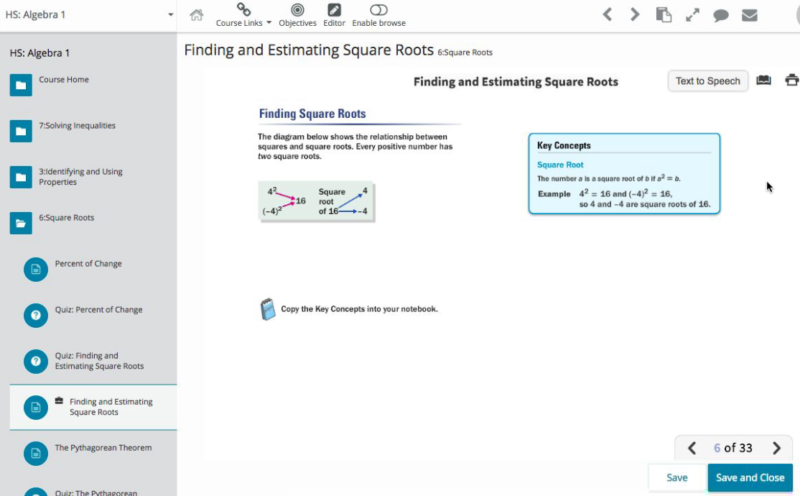

Brown liked the shift to online work. He found it was an adjustment to have to typewrite assignments instead of writing them by hand, but he liked being able to take classes he actually needed and to move through them at his own pace. Brown says he took several English courses online, along with social studies, environmental science, geometry, algebra, and music, among others.

Teachers, he said, were always there to help.

“You can get however much help you want if you’re serious about it,” Brown said, adding, “a lot of people weren’t serious.”

Of course, there is variation across the five Illinois Department of Juvenile Justice sites, and not all students have had experiences as positive as Brown’s.

Lindsay Miller, an ACLU attorney who has been monitoring the department’s compliance with the settlement agreement, said she has seen an overreliance on the online program, threatening the balance required for blended learning.

“It really ends up being computer-led — where the teachers are monitoring, they’re not really instructing,” Miller said. “Youth are saying ‘this isn’t something I can teach myself, I need more direct instruction.’ ”

Algebra is among the courses students can take online as part of a blended learning program instituted by the Illinois Department of Juvenile Justice.

The pace at which students can complete an entire course for credit also troubles education experts. Some District 428 students earn double the number of credits common in a traditional academic year. The pace is much like online credit recovery programs, which allow students to retake an entire semester’s worth of failed classes in a matter of weeks. Critics of these programs — and their arguably too-good-to-be-true outcomes — question whether students are actually learning the material they set out to learn, or just being shuttled along for the credits that set them up for graduation.

Peter Leone, a professor in the University of Maryland College of Education with decades of experience providing expert testimony in court cases alleging inadequate educational opportunities for incarcerated youth, has mixed feelings about online learning as a solution to the challenges of educating these students.

“There are a group of kids for whom it can be very effective and efficient and it can give them an opportunity to catch up,” Leone said. “Kids who struggle academically, who have not experienced a lot of success in school, many are kids eligible for special education services — for these kids, a strictly online program is not terribly effective.”

Some facilities seem to make blended learning work better than others.

The Illinois Youth Center-Pere Marquette, a minimum-security facility in southern Illinois, has an average daily population of just 36 boys. Principal Cynthia Houston said teachers serve closer to 25 students per day because the others have already graduated from high school and are either in apprenticeship programs or taking college courses on the nearby Lewis and Clark Community College campus.

At IYC-Pere Marquette, Houston describes a high-functioning blended-learning model, in which students do get personalized attention from teachers as they work through the online courses. On computer-free Wednesdays, teachers lead lessons on topics that routinely trip up students, addressing a particular math or literacy skill with the whole group, for example. There are also monthly themes that drive lessons and activities — African-American history in February, health, and nutrition in March.

Houston said the average class size is just three or four students. She believes this makes a big difference, ensuring that the blended-learning model is not simply aspirational. Students really do get a mix of self-driven online time along with opportunities to develop relationships with and learn directly from their teachers. Houston credits small class sizes with the increasing graduation rates at her school.

“We’re able to give the youth that one-on-one,” she said.

Contrast that with Illinois Youth Center-St. Charles, a medium-security facility west of Chicago that has about 138 boys on any given day. Staff shortages and security concerns regularly keep kids from class — the center had 17 cancellations or disruptions in July 2017 alone, according to Leone.

The Illinois system is far from fixed. But no one could argue that it has not improved. And one beneficiary of that is Marquell Brown, who says he knows his diploma will help him get a job. And he is confident now in his ability to read and to do the math, skills he honed in juvenile justice classrooms.

“It’s like, we in jail temporarily, so why not? Why not go to school? Why not learn something while we’re here?” Brown said. “One thing I learned, if there’s anything people take from you, they can’t take your education away from you.”

Produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for The Hechinger Report Newsletter.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.