One year of COVID: 5 Philly area residents reflect on what they’ve lost — and found

A doctor. A business owner. A student. A musician. A therapist. Five Philly area residents share their reflections on the past year of the pandemic.

March marks one year since the coronavirus pandemic took hold in the Philadelphia region, completely changing many aspects of our lives as we knew them and exposing deep racial and socioeconomic inequities.

Many of us have lost loved ones, jobs, or connections with others. But we’ve also found new ways of doing things, picked up hobbies, and learned more about ourselves.

WHYY News spoke to five Philly area residents about what they’ve lost and what they’ve found over the past year, and how they’re moving forward:

A musician without a stage

Amir ‘The Bul Bey’ Richardson, musician/multimedia creator, and WHYY community curator

Before the pandemic, Amir was used to recording in about five studio sessions every week. He was very active performing, hosting festivals, and collaborating across Philadelphia. Now, he’s only had two studio sessions in the past year, and he collaborates by recording and sending tracks from his phone. He spends most of his time alone in a one-bedroom apartment in West Philadelphia.

“I felt like a machine a little bit. You know, I cut all the things that kind of made me a person in terms of family, friends, music, art, community, stuff like that. I couldn’t indulge in any of those things.”

Amir lost his grandfather in February, not long before the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic. His Pop-Pop, as Amir calls him, lived in an assisted living facility. It was never confirmed, though Amir suspects he may have had COVID-19.

Amir has dealt with his grief by diving deeper into his music. The pandemic forced him to spend a lot of time with himself, so he’s been reflecting on who he is and how he connects to the Philadelphia community, especially after the protests and racial reckoning this past summer.

“I was really trying to figure out, how does my voice fit into any of this? How do I fit into, you know, tearing down power structures and supporting people that need to be supported, and holding space and creating space, and all those different things? And music is that. Creativity is that …

“I’m always reminded how important the arts are. It adds human depth to the spirit, the soul … I’ve learned recently that part of the reason why I even was propelled into music is because I was processing trauma. And the arts is just so important for that …

“I think we all felt like we understood what was going to happen tomorrow and the day after, prior to the pandemic. But now we all understand, you can’t predict the future. No one knows what is going to happen. So if there’s something that you want to do, get it done now. You know, speak up right now. Playing the sideline just doesn’t work too well.”

An ER doctor who found time for family

Dr. Priya Mammen, emergency physician and public health specialist

Priya has been treating COVID patients in an emergency department in Chester County. She noted how it can be more difficult to access health care in rural areas, where the closest medical facility can be fifteen or twenty miles away. She treats people across the board, from canning and manufacturing workers to wealthy landowners. The hardest part for her has been seeing people refuse to wear masks and reject safety guidelines while she and her team are fighting to save lives every day.

“I never questioned that everybody believed that we should save lives. I never questioned that the general value system was that we do whatever we can for each other … People are still traveling, and there are people who still think this is not a big deal … Are we learning something? Are we getting better, or are we just trying to keep our heads above water?”

She spoke about the graphics in media outlets like the New York Times that show COVID-19 cases and deaths as dots on a map.

“If you’ve never had the experience of having to tell someone that someone they love has passed away, it’s easy to sort of get dehumanized by those dots … to feel that those dots are just dots. But they are families, and they’re communities.”

Still, Priya said she has found hope in the small moments she never noticed before. With her ER schedule in the past, there have been times when she went five or six days without seeing her two sons. Now, she’s appreciating the chance to be home with them when she’s not at the hospital.

“I am completely loving spending time with my family and all of us kind of living moments together … I think it’s very easy to overlook in this constant grind we were in … It’s kind of made some of the other stuff quiet, and so you can hear things clearer. Those other things that may have been in the background or easily drowned out, now are what’s around you. And it’s pretty amazing to live those moments.”

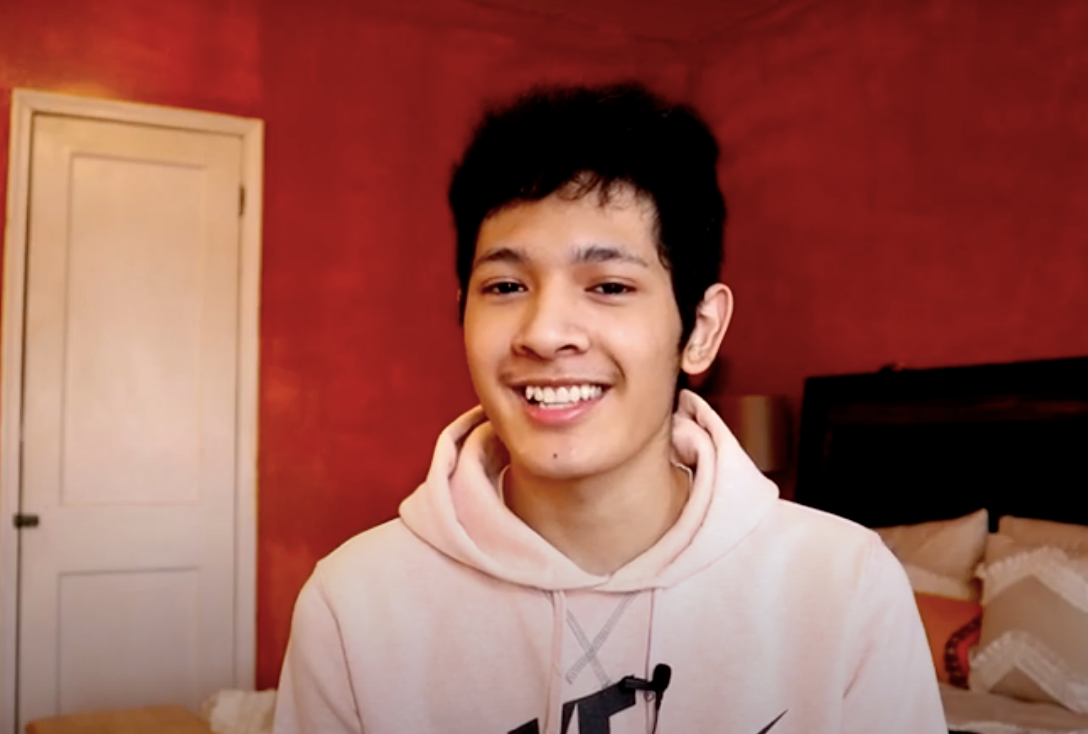

A student who reconnected with his identity

Sammy Sacksith, Carver High School senior, member of WHYY’s Pathways to Media Careers, Youth Employment Program

Sammy’s senior year of high school has been very different from what he expected. He’s balancing online classes with added responsibilities at home, helping with cleaning, babysitting, and taking care of his dog. Despite those challenges, he found the time to start a new club that celebrates Cambodian identity.

“For the longest time, I just felt like another Asian person, even to other Asian people. And the older I grew and the more I thought about it, the more I realized how many of my lived experiences and things that Cambodian people go through just are not represented. So I ultimately started it out of those reasons, to give a platform and a voice to Cambodian identity.”

The club has drawn in about 20 students in its first year, many of whom are not Cambodian, but are interested in learning about the culture. They held a cooking showcase over Zoom, and Sammy says he was proud to see that the attendees filled more than two screens. He said he would have been too intimidated to start this club in person, but at home, he felt more comfortable.

“After it was done, I could just shut off Zoom, walk away and take a breather to process what was going on. You know, that was a good thing.”

He’s also taken the time at home to get more in touch with himself as he prepares to make a major life transition.

“Moving from high school into college, it filled me with this anxiety of ‘What’s life going to be like? How much am I going to have to deal with?’ It was anxiety upon anxiety upon anxiety. The way I dealt with that was … I knew it was okay to feel whatever it is I felt … The shred of optimism that was inside me finally came out organically. It’s just this underlying idea that I can be positive about myself.”

A therapist who found she needed healing

Saleemah McNeil, reproductive psychotherapist, Founder and CEO Oshun Family Center

Saleemah and her family had COVID-19 in April. Her symptoms were most acute during Black Maternal Health Week when she had a slate of virtual events to run, but she felt obligated to work through it — something she says she would never recommend to her therapy patients. She says this feeling of having to keep going and going is common among Black women.

“Black women are resilient and we have been taught for generations that we endure and push through. There is this feeling of responsibility that we have to show up, and not only show up, but show up your best self.”

With the help of her community, Saleemah recovered, and in June — after the protests over the police killing of George Floyd — she started raising money to offer free mental health care to other Black people. She began by asking for $5,000. In just one day, she got $7,000, and by now she’s raised over $100,000.

The initiative took off, but the extra work and the pressure of so much media attention and people who needed help eventually took a toll on Saleemah’s own mental health. She decided to pause in November and take a vacation with her family, learning that once she slowed down and took care of herself, she would be better able to care for others.

“I had to realize that I wasn’t functioning in my true authentic fashion and I was sitting in some of the tales that were told, some of the stereotypes that we had, and that it was okay for me to let those go.

“And just being able to lose that and then find not only parts of myself, but a silver lining for my community as well — I found so many Black people who want therapy. I found so many Black moms who needed services, and we were able to provide that for them. And I think that was a population that unfortunately, if we didn’t all go through this together, I may not have been able to reach.”

An entrepreneur who met the moment

Dan Tsao, owner of Metro Chinese and Metro Viet Weekly, restaurant owner, founder of Rice Van, member of WHYY’s News and Information Community Exchange

Dan owns several businesses, but last year, he says none of them were “pandemic proof.” His Chinatown restaurant, EMei, lost customers as early as February, because many Chinese Americans became cautious when they saw COVID-19 spreading in China. In March, his newspapers suddenly lost advertisements from clients who had been working with him for over ten years.

Dan needed a new source of revenue, and he knew that his customers and readers in the suburbs lived too far away to order from EMei on delivery apps like GrubHub and DoorDash. So he started his own service, called RiceVan, to deliver orders from Chinatown restaurants and specialty Asian groceries to people up to 60 miles outside of Philadelphia. Soon, RiceVan was bringing in enough revenue to not only keep all of his current staff employed, but to add 15 new positions.

“We received thank you letters from our customers, and they’re asking us, ‘Could you please keep this service going even after pandemic?’”

Starting a new business is never easy, much less during a pandemic. Dan and his media team, who were used to working behind desks, had to roll up their sleeves and do a lot of the frontline work. Even Dan himself became the backup driver for RiceVan.

Dan has three children, and he says all this extra work has taken a toll on his family. He feels like he’s back where he was when he first started his newspapers 13 years ago.

“I think everybody knows during the start up, you have to give up so much. You need to give up the time with your family … You give up your social life. I think for the pandemic, I feel that it put me back right into the spot 13 years ago. I mean, you have to put yourself back into the reality that if I don’t pick up the hardworking spirit, be resilient, be persistent, everything can be gone.”

Still, Dan said he is glad that he was able to find a new path in the pandemic. He’s kept his team together, helped customers, and helped other restaurants increase their revenues.

“I think it is a win-win situation for ourselves and also for the customers, as well as for the vendors. Because of Rice Van, we found new tractions in our projects. We found new directions.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)