New Pa. plan could help 220k students attend private school, putting a fifth of the state public school budget at risk

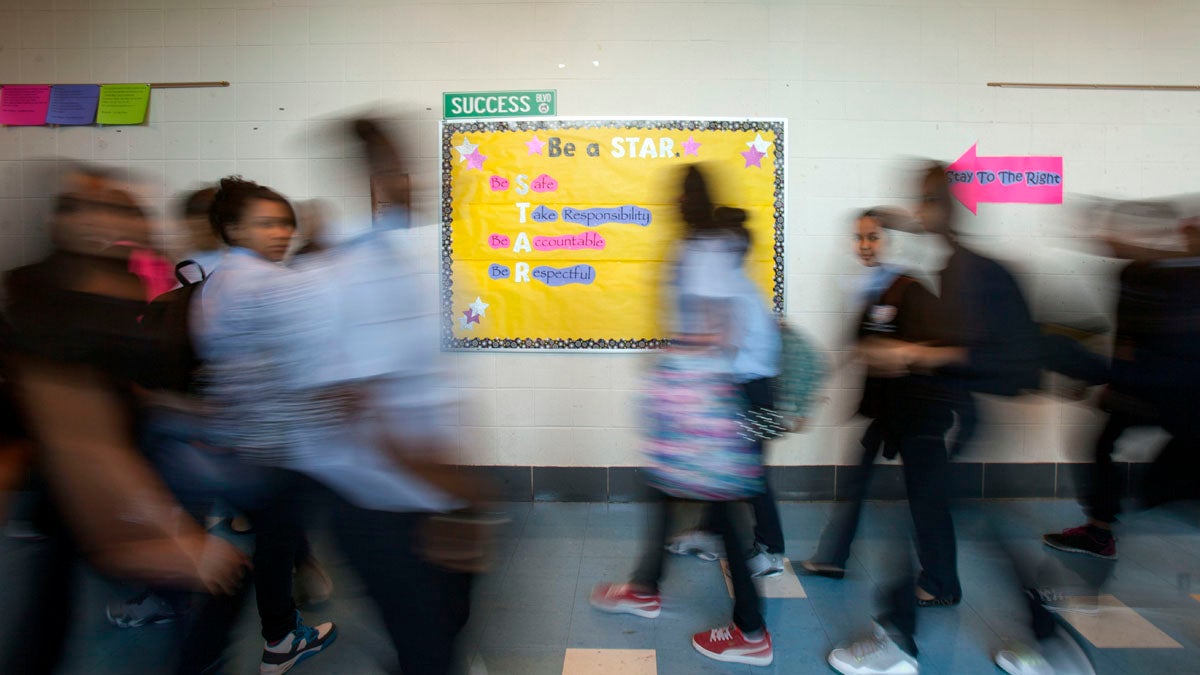

Middle school students change classes (Jessica Kourkounis for WHYY, file)

A powerful coalition of Pennsylvania lawmakers is promoting a forthcoming education savings account (ESA) bill that would allow hundreds of thousands of students in the state to use public money to pay for private school tuition.

The proposal could dramatically alter the state’s K-12 education landscape, potentially siphoning away about a fifth of the state’s overall support for public schools.

With this savings account plan, funds currently allocated for support of public schools would be deducted from state coffers and made directly available to parents to help cover the cost of a list of education-related expenses including private school tuition, textbooks, industry certifications, and tutors.

“The people of the United States have decided to fund education in a public manner, but they have not given the government authorization to decide where children go to school,” said John DiSanto, R-Dauphin County, the bill’s lead sponsor. “The world’s changing.”

The plan aligns with the priorities set forth by President Donald Trump and U.S. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos.

Eligibility would be limited to parents who have a student currently attending a public school who live within the catchment of a public school deemed by the state to be in the bottom 15 percent of quality based on standardized tests.

Funds would be distributed and overseen by the state treasury. Each student would be entitled to $5,700 per year, the average total per pupil allotment that school districts in Pa. receive from state government.

How many students would that affect? How much of the state’s education budget could be impacted?

“I’m not sure what the number of kids are in the bottom 15 percent,” said DiSanto, a freshman senator.

A Keystone Crossroads analysis of enrollment data found that there are currently more than 220,300 such students in nearly 400 schools spread across 44 of the state’s 67 counties.

So, potentially, that means $1.7 billion dollars could be taken away from public schools, possibly forcing the need for further school closures and consolidations.

State Senator Vincent Hughes, D-Philadelphia, believes the plan would be an abdication of the legislature’s constitutional responsibility to support a “thorough and efficient system of public education.”

“It takes the limited dollars that are in the system and takes them out of public education, and drives them into private schools with no accountability and no oversight of what happens in those schools that are using public taxpayer’s money,” said Hughes.

How would he respond to a parent in his district who was enthusiastic about the chance to send their child to private school, someone unwilling to wait any longer for the traditional system to improve?

“It would be a difficult conversation,” said Hughes, “but we have to have the conversation in the context of the whole. Are we in support of taking money from one child who is deserving of funds and giving it to another?”

In Philadelphia, by far the state’s largest district, at least 85,000 students in 146 schools would be eligible. As currently proposed, students who attend a charter or a magnet school who live within the catchment of a bottom-ranked school would also be eligible for the ESA.

DiSanto’s office downplayed the idea of a large cut to public school coffers, saying the program likely wouldn’t reach maximum eligibility. The office pointed to examples elsewhere where participation rates have been only a small fraction of the school-aged population.

National context

Five states currently have education savings account laws on the books, but Pennsylvania’s plan does not have much practical precedent.

Florida, Tennessee, and Mississippi limit eligibility to special education students. Arizona has been on the vanguard of the issue, becoming the first state to pass ESA legislation in 2011. Its program is ramping up to include all students, but push back has forced the issue to a public ballot.

In Nevada, technically, all students can sign up, but a political squabble has left its ESA program completely unfunded.

DiSanto believes there, like here, opponents are valuing traditional systems over the needs of disadvantaged children. He says all schools will improve with greater competition.

“The public schools actually do a better job as well because class sizes can be smaller, they have to compete, it raises everybody’s boat,” he said. “So this is not an attack on public schools at all.”

The bill would not force participating private schools to administer and report scores on the state standardized tests as public schools must, nor would it push those schools to alter any enrollment practices that seek to minimize accepting students with special needs or challenges.

DiSanto downplayed the effectiveness of standardized tests as a school accountability tool.

“Public schools are no more accountable than they were 10, 15 years ago. And the real point of fact here is that the parents are the real accountability factor. If people are willing to pay for their kids to go to different educational options, they are going to be holding those providers accountable.”

The state compiles its bottom 15 percent of schools list entirely based on standardized test scores.

That list exists to determine eligibility in the state’s existing Opportunity Scholarship Tax Credit program, created in 2012, where businesses get state tax breaks for donating to organizations that give scholarships to students to help them pay for private school. That program is currently capped at $50 million per year.

OSTC and ESA share many of the same allies and critics. But unlike OSTC, the ESA plan would have no cap, and it would be funded directly from existing state resources appropriated for public schools.

The ESA plan bears much resemblance to the private school voucher plans touted by Republican Governors Tom Ridge and Tom Corbett. Those efforts never garnered enough support among lawmakers.

DiSanto plans to formally introduce his bill in September. It has the backing of Senate Education Committee Chair John Eichelberger, R-Blair, and Senate President Pro Tempore Joe Scarnati, R-Jefferson.

If the bill makes it through the legislature, Governor Tom Wolf, a Democrat, has indicated he’d block it with his veto pen.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.