Many coastal New Jersey homeowners lack flood insurance despite rising seas, report says

A gap in flood insurance coverage leaves millions at risk as the frequency and severity of extreme weather events increase across the Northeast, the report notes.

Max Sorensen paddled through his neighborhood in Stone Harbor after flooding caused by a major storm in 2016. (AP Photo/Ted Shaffrey)

This story originally appeared on NJ Spotlight.

Despite the rising seas and bigger storms brought on by climate change, millions of vulnerable homeowners in New Jersey and the rest of the Northeast are uncovered by federal flood insurance because they can’t afford it or don’t think flooding will impact them.

So says the federal government’s latest National Climate Assessment, the nation’s report card on climate change.

The document, the fifth in a series, says public and private finance is increasingly being used throughout the United States to mitigate and adapt to the effects of climate change — but that more is needed to make communities resilient to rising seas, droughts, floods, wildfires and hurricanes.

The analysis of how society is trying to pay for climate action is just one aspect of the wide-ranging report, compiled by some 800 scientists in 14 federal agencies, and mandated by Congress. It also looked region-by-region at how the changing climate is affecting water, energy, land, forests, ecosystems, coasts, oceans, transportation and the built environment.

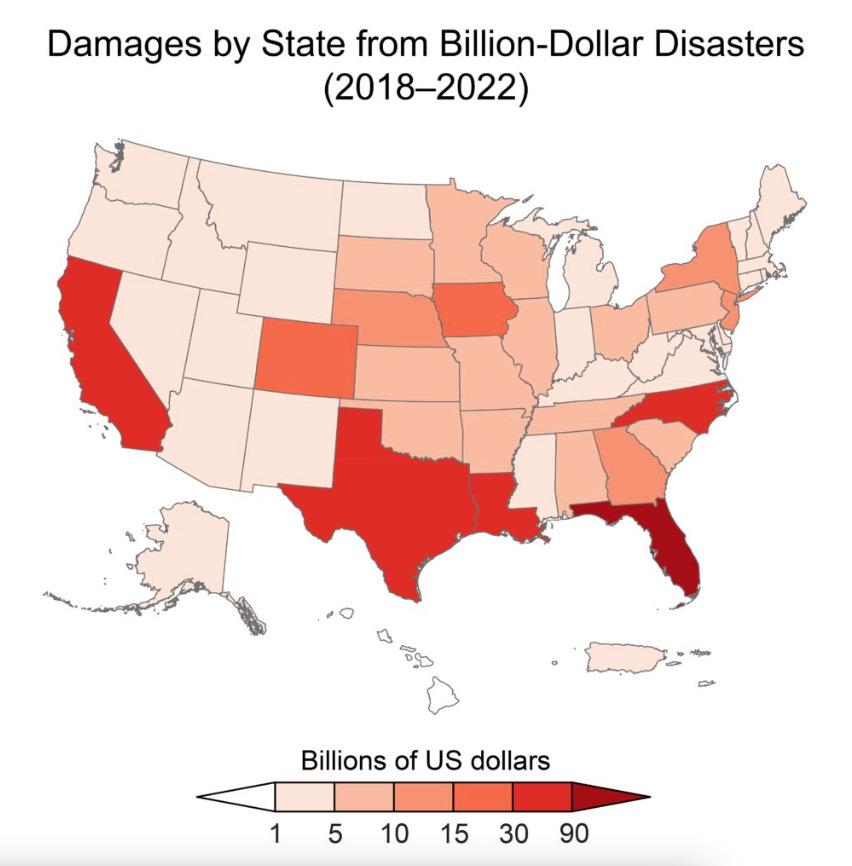

The report devoted a full chapter to the economic impacts of climate change, noting that communities will face high costs for defending coastal areas from rising seas or elevating roads, but may also enjoy economic opportunities such as more jobs in renewable energy.

On the financial threats of climate change, it noted that about half of fire and wind damage nationally is covered by insurance, but only 12%-14% of homeowners are covered for flood damage by the federal National Flood Insurance Program.

Financial risk

“This ‘gap’ in flood insurance coverage leaves millions at risk of financial hardship as the frequency and severity of coastal and rainfall flood events across the Northeast are expected to increase,” the report said.

During Superstorm Sandy in October 2012, some 72,000 New Jersey homes and businesses were destroyed or damaged by wind or flooding, according to the Federal Emergency Management Agency. In September 2021, Tropical Storm Ida devastated many inland areas of the state, killing 30 people and causing more than $2 billion in property damage, state officials estimated.

By 2030, the sea level at the Jersey Shore is projected to rise by 0.5 to 1.1 feet from its 2000 level, according to a separate Rutgers University forecast. The range of the forecasts increases to between 0.9 and 2.1 feet by 2050. Forecasts for the rest of the 21st century vary according to the quantity of greenhouse gases that are pumped into the atmosphere, and that will depend on how successful global governments are in driving down carbon emissions from sources like cars and power stations.

The Rutgers projections for sea-level rise are broadly in line with those in the new report. It projects seas around the U.S. coastline will rise another 11 inches by 2050. That would leave some areas of the Jersey Shore uninhabitable, raising the prospect that some coastal communities in places such as Cape May and Cumberland counties might be required to move inland, a process known as “managed retreat.”

In New Jersey, relocation of communities from the most flood-prone areas is headed by the state’s Blue Acres program, which buys homes from willing sellers and then demolishes the buildings to create open space that helps to defend remaining homes from flooding. The program, which has purchased about 1,000 homes since it began in the 1990s, then helps the affected residents to find new homes on higher ground.

Out-of-date flood maps

On the costs of adaptation, the new report said many homeowners are unaware that some FEMA flooding maps are decades old and do not accurately represent flood risk in some areas. Since mortgage lenders don’t require flood insurance for homes that are outside a FEMA-designated Special Flood Hazard Area, homeowners there assume there is no risk, and decide not to take government coverage, it said.

Even for those with federal flood insurance, payout limits on National Flood Insurance Program policies are capped at $250,000 for residential properties, around $100,000 lower than the median value in the Northeast, leaving policyholders potentially exposed if their homes are destroyed, the report said. And it said there’s insufficient enforcement by mortgage lenders that owners in flood-prone areas must be insured, leading about one-third of policyholders to simply drop their policies after an initial period.

In the private sector, 13% more money has been spent on climate measures globally since 2018, and about a quarter of that is in the United States and Canada. But nearly all the new money is for mitigating climate emissions with wind and solar power and electric vehicle charging stations, leaving little for adaptation.

Although there is “ample” private capital available that could be used for adaptation projects, there is a perception among the business community that those projects won’t return enough on investment, the report said.

Some hope

In the public sector, state and local governments have traditionally borne most of the costs of building climate resilience, but they are burdened by the cost of preparing infrastructure for climate change when it is already old and inefficient, the report said. It noted that the American Society of Civil Engineers in 2021, in its annual report card on America’s infrastructure, gave the infrastructure of the Northeast states no higher than a C grade.

Still, there have been “historic” levels of federal funding to states, tribes and local governments for pandemic relief and climate-resilience spending, while states in the Northeast have been issuing general obligation bonds to raise capital for climate-related measures, the report said.

Despite its gloomy predictions, the report tried to convey some optimism, at least, and argued that humans can still avoid the worst climate change effects by cooperating to cut greenhouse gas emissions.

“While there are still uncertainties about how the planet will react to rapid warming, the degree to which climate change will continue to worsen is largely in human hands,” it said.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.