New Jersey’s adoption numbers are down. Here’s why

The goal of the N.J. Department of Children and Families is birth-family reunification, but when that’s not possible, adoption is an option.

Over the past several years, the number of adoptions in New Jersey has been slowly trending downward. There were 514 children adopted in 2021, compared with 385 in 2024, said Brandi Harding, the Department of Children and Families deputy director of the Division of Child Protection and Permanency.

The department’s assistant commissioner, Laura Jamet, said the number has been dropping because reuniting children with their birth families is considered the best option, whenever possible.

“Our belief is that children really need to remain with their families if it’s something we can do safely,” she said.

According to the National Institutes of Health, family reunification is considered the best solution for the well-being of children if dysfunctional family patterns can be rectified through intervention.

When the New Jersey DCF was created in 2006, an extensive network of health services was developed to protect at-risk children.

Those efforts were enhanced in 2018, when the federal government enacted the Family First Prevention Services Act, which offered child welfare departments in states across the nation the opportunity for federal cost-sharing in prevention services.

Other options

Harding said that while family reunification is a primary goal of DCF, alternative options may need to be considered. She said one option is kinship legal guardianship.

“You don’t have to have a termination of parental rights,” she said. “It can be with family members or family friends that the child knows.”

She said in this program the court may permit visitations with birth parents and, depending on the situation, parents may be able to regain custody.

“Sometimes a couple of years go by, and maybe what was not safe for a child changes,” Harding said. “Now parents have made different choices, they have remedied the safety issues, and now they’re in a place that they can petition [the court] to get custody of their children back.”

Research finds kinship care results in fewer behavioral problems for children than traditional foster care settings.

If guardianship is not feasible, a child may be placed in a foster home, also known in New Jersey as a resource home.

Ultimately, if reunification with the birth family is unsuccessful, there will be a termination of parental rights, which usually takes a year, but can take up to three years.

“It really depends on the parents,” Harding said. “Does the parent surrender their rights, or do they go through a guardianship trial? Do they appeal the decision? All of that can take time.”

When parental rights have been terminated, children are deemed to be legally free, and an adoption can take place.

The adoption alternative

Middlesex County resident Kelly McGlasson decided when she was 8 years old that she wanted to adopt two children.

“In third grade, I wrote a Christmas story about adoption, about two foster kids. All they wanted for Christmas was a family,” she said.

When she was growing up, McGlasson knew kids in her neighborhood who spent time in the foster care system. They had experienced domestic violence with their birth families, and it made a strong impression on her.

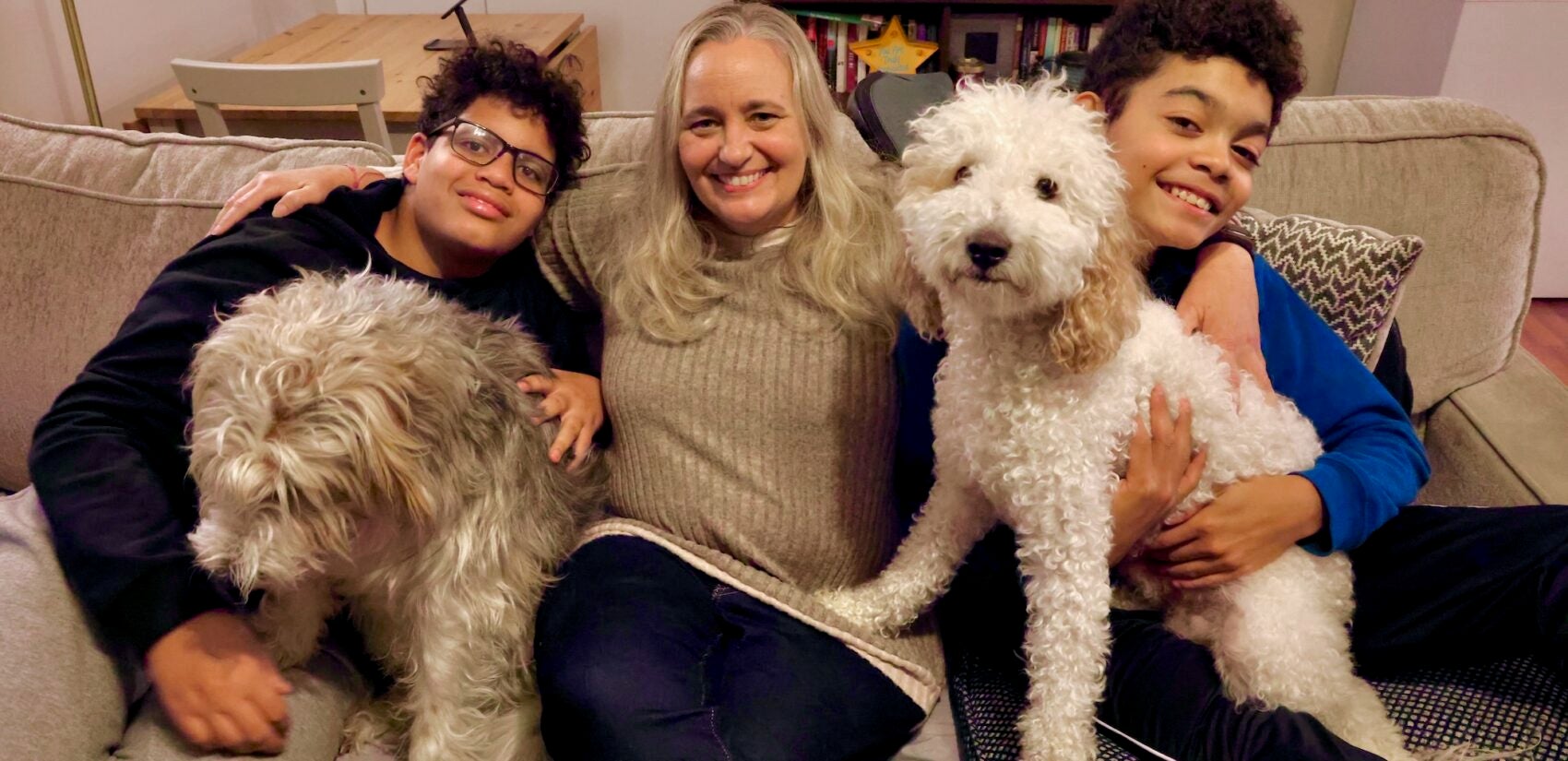

In 2014, McGlasson became a foster parent. Five years later, she realized her childhood dream and adopted an 8-year-old boy named Geo. She continued to foster children, and in July 2025, she adopted a second son, Derek.

McGlasson said she is embracing the challenge of being a single mother of two.

“Teenage boys eat a lot to begin with, but they both went through food insecurity when they were young,” she said. “There are so many needs that weren’t met when they were younger, that they are working through now.”

She continues to foster children in need.

“I think about how that child feels and I want to be that safe place. I want to give them that love so they can take that with them wherever they go and remember that they do matter, that they are important,” McGlasson said.

She said being an adoptive and foster mom has given her a strong sense of purpose, brought her joy and helped her build resilience as she helps children work through the trauma they have faced in their young lives.

“You should do it, because there are so many kids out there that just need to feel safe and valued and loved,” she said.

Adoptive parents are needed

DCF’s Harding said adoptive parents are wonderful, but they’re not super-human.

“They’re everyday people just like you and me, everyday people who believe in the values of families and connections and humanity and wanting to help people,” she said.

She added that every child is precious and special.

“Regardless of their age, every child deserves to have that loving, nurturing, stable and safe home environment,” McGlasson said.

There is a strong need for adults who care, said Jamet, the department’s assistant commissioner.

“For a child to be able to achieve permanency and find that safe, loving and permanent home is such a huge new chapter in their life,” she said. “We ask those with open hearts to join us in this effort.”

Harding said adoption opportunities are available for all kinds of families.

“We really are interested in finding families for our teens, for our sibling groups, so we can keep siblings together, and our children with medical needs,” she said. “We really need families from all walks of life.”

She said whether someone is a seasoned parent or parenting for the first time, they can get involved and make a difference.

“If you can provide a safe, stable and nurturing home we want to invite you to join our village of resource parents and our child welfare professionals,” she said. “We can work together to help our children in New Jersey thrive.”

The Department of Children and Families has 45 local offices across the state, each one with an adoption unit, and information is also available online. The Department also maintains a website, Meet the New Jersey Kids, that features children who are legally free to be adopted.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.