New federal report surprises: Philadelphia poverty down, income up

Philadelphia’s poverty rate, a stark and stubborn indicator of hard times that has long hindered the city’s reputation, dropped to its lowest level since 2008.

Russell Hadlock, 49, sits outside the St. Francis Inn, a soup kitchen for low-income and homeless people, in Philadelphia's Kensington section on Wednesday. (Stephen M. Falk/The Philadelphia Inquirer)

Philadelphia’s poverty rate, a stark and stubborn indicator of hard times that has long hindered the city’s reputation, dropped to its lowest level since 2008 — near the start of the recession.

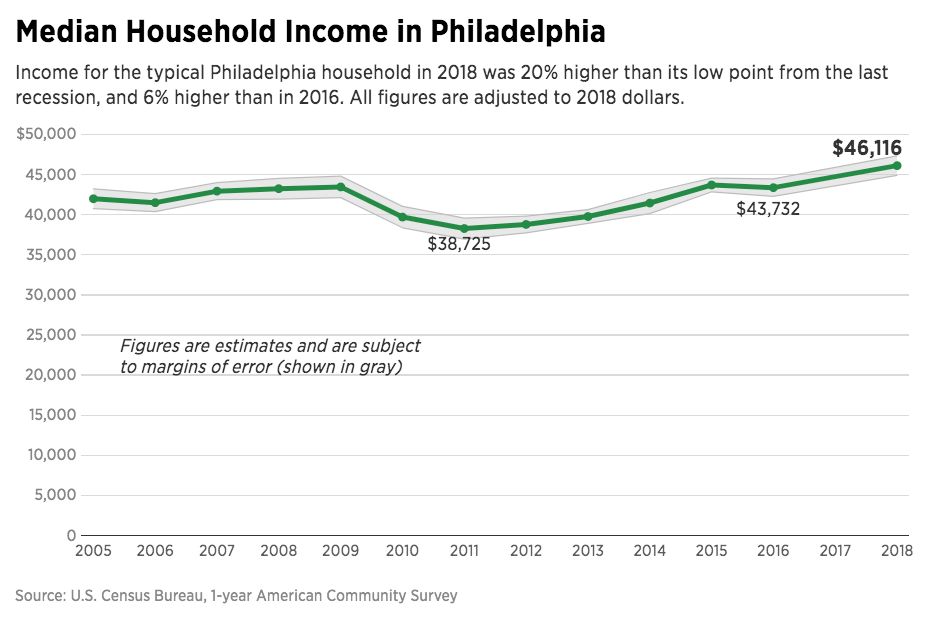

At the same time, median household income here rose.

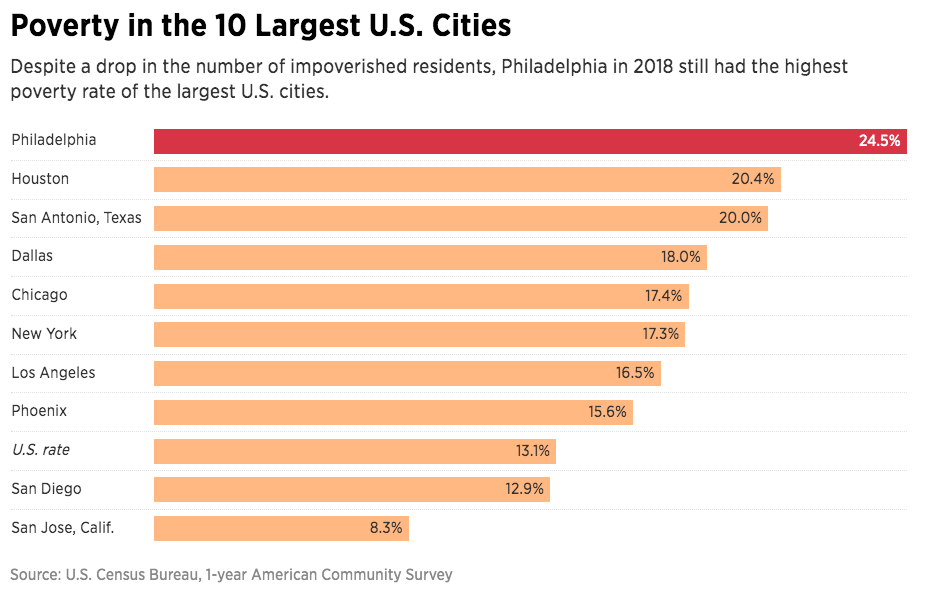

The findings, contained in a voluminous report from the U.S. Census Bureau released Thursday, showed that the city’s poverty rate declined from 25.7% in 2016 to 24.5% in 2018. The number of Philadelphia residents living in poverty dropped by 14,537 — from 391,653 to 377,116 — while the median household income (adjusted for inflation) increased from $43,372 to $46,116.

In a rare and startling addendum to the report, known as the American Community Survey (ACS), the Census Bureau said that the data contained in last year’s release, which depicted poverty, income, and other aspects of life in Philadelphia in 2017, were incorrect. Census officials advised that the erroneous statistics for that year not be used in making comparisons. That admission roiled some city leaders, at the same time confirming their suspicions that those figures had been wrong all along.

Like a busted needle stuck in the red zone, Philadelphia’s poverty rate had not dipped below 25% since 2008. Economists, city officials, and some antipoverty advocates, then, were gratified to see a positive fluctuation in poverty, as well as in household income.

“It’s meaningful improvement, particularly the healthy gain in median income,” said Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics. “It goes to the strength of the Philadelphia economy, which is about as strong as I’ve ever seen in terms of wage growth, unemployment, and number of jobs.”

Ira Goldstein, president of policy solutions at the Reinvestment Fund in Philadelphia, a financial institution that helps low-income people, thought the ACS findings made sense.

“There’s no reason we shouldn’t have a lower poverty rate,” he said. “The unemployment rate in the city in May was 4.9%, down from 6.7% in 2016. We went from 653,000 employed to 681,000.”

Not surprisingly, Mayor Jim Kenney’s office was pleased.

“It gives us hope and confidence that we are making progress,” said Maari Porter, deputy chief of staff policy and strategic initiatives in the mayor’s office. “But there’s no denying one-quarter of Philadelphians in poverty are still too many.”

Still, she cited beneficial city policies of “supporting people who need help with housing and eviction,” focusing on workforce development and expanding pre-K for children.

Philadelphia echoed national trends that show poverty is dropping. The U.S. poverty rate took a 0.5 percentage point dip, from 12.3% in 2017 (non-Philadelphia census numbers from 2017 are considered fine to use) to 11.8% last year. The U.S.

While encouraging, the Philadelphia numbers aren’t all good.

For example, Philadelphia remains the poorest of the 10 most populous U.S. cities, the ACS showed. The number of people in poverty here is roughly equivalent to the entire population of Cleveland.

Further, its childhood poverty rate was 34.6%, compared with around 20% nationwide. And while its deep poverty rate — a measure of people living at 50% of the poverty line or below — dipped somewhat in 2018, it came in at 11.1%, the highest among cities with a population of one million or more. The poverty line for a family of three in 2018 was $20,780.

Some poverty experts were unimpressed with the ACS.

“No one should be doing a victory lap,” said Joel Berg, CEO of Hunger Free America, a national nonprofit. “Philadelphia still has one of the highest poverty levels in the Western world.”

Mariana Chilton, a director of the Center for Hunger-Free Communities at Drexel University, and the leading local expert on hunger, said the numbers weren’t significantly different than past data and demonstrated a sad “status quo” in Philadelphia. “The brilliance and potential of people living in poverty are squandered through bad policies and empty promises of incremental change,” she said.

Glad to see that people moved out of poverty, and that the median household income trended upward, Ashley Putnam, director of the economic growth and mobility project of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, nevertheless wondered whether enough people are sharing in the improved conditions.

The ACS income data challenge the phrase “A rising tide lifts all boats,” she said. “Are all residents benefiting from the rising tide?”

Measuring poverty and income elsewhere, the ACS showed that poverty rates in New Jersey dipped slightly between 2017 and 2018, from 10% to 9.5%. In Pennsylvania, poverty also slid downward, from 12.5% to 11.7%.

As for median household income, New Jersey saw a 2% growth, from $80,088 in 2017 to $81,740. “Up” was the watchword throughout Pennsylvania, with income rising from $59,195 to $60,905, a 3% bump.

The counties around Philadelphia yielded a mixed bag of data.

In a puzzling finding, median household income in Gloucester County dropped by more than $7,600 between 2017 and 2018, from $89,496 to $81,849, the biggest decline in the region. At the same time, poverty showed a 1.6 percentage point rise. County officials were at a loss to explain why.

Meanwhile, Camden County confounded observers by registering increases in both income and poverty. Income popped up 2% from $66,196 to $67,523. At the same time, however, poverty rates somehow climbed from 11.5% to 13.3%, the 1.8 percentage point jump the largest in any county in the region.

It’s likely a variation on the notion that the rich get richer, and the poor stay stranded, said Mujiba Salaam Parker, grant manager at the Camden County Council on Economic Opportunity.

“The middle class here saw a rise in income, and state incentives relocated lots of businesses to the city of Camden,” Parker said. But the office jobs could not help those in poverty, who lack the computer skills to work in such places, she added.

Bucks County, meanwhile, showed a 5% increase in median household income ($84,749 to $88,569), the largest rise among Philadelphia’s suburban counties on either side of the river.

Marissa Christie, president and CEO of United Way Bucks County, was at a loss to explain. “I’m having a hard time reconciling an increase in income while our unemployment rate increased from 3.4% to 4% between June and July,” she said. “There’s a very high cost of living here. And at any moment, people’s families can be derailed.”

It’s true, no one expects to be mired in poverty, noted Robert Locke, 71, a retired security officer living on Social Security in Northeast Philadelphia. But it has a way of sneaking up on people.

Having suffered through a heart attack, triple bypass surgery, and three strokes, Locke, who is separated and is the father of five grown children, noted: “I’m learning a lot about poverty. I didn’t realize you could get sick, and then life could come down on you.

“You can never expect the unexpected. And you don’t know what tomorrow is going to bring you.”

WHYY is one of over 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push towards economic justice. Follow us at @BrokeInPhilly.

WHYY is one of over 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push towards economic justice. Follow us at @BrokeInPhilly.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.