Movie theaters strike back in downtown Philadelphia

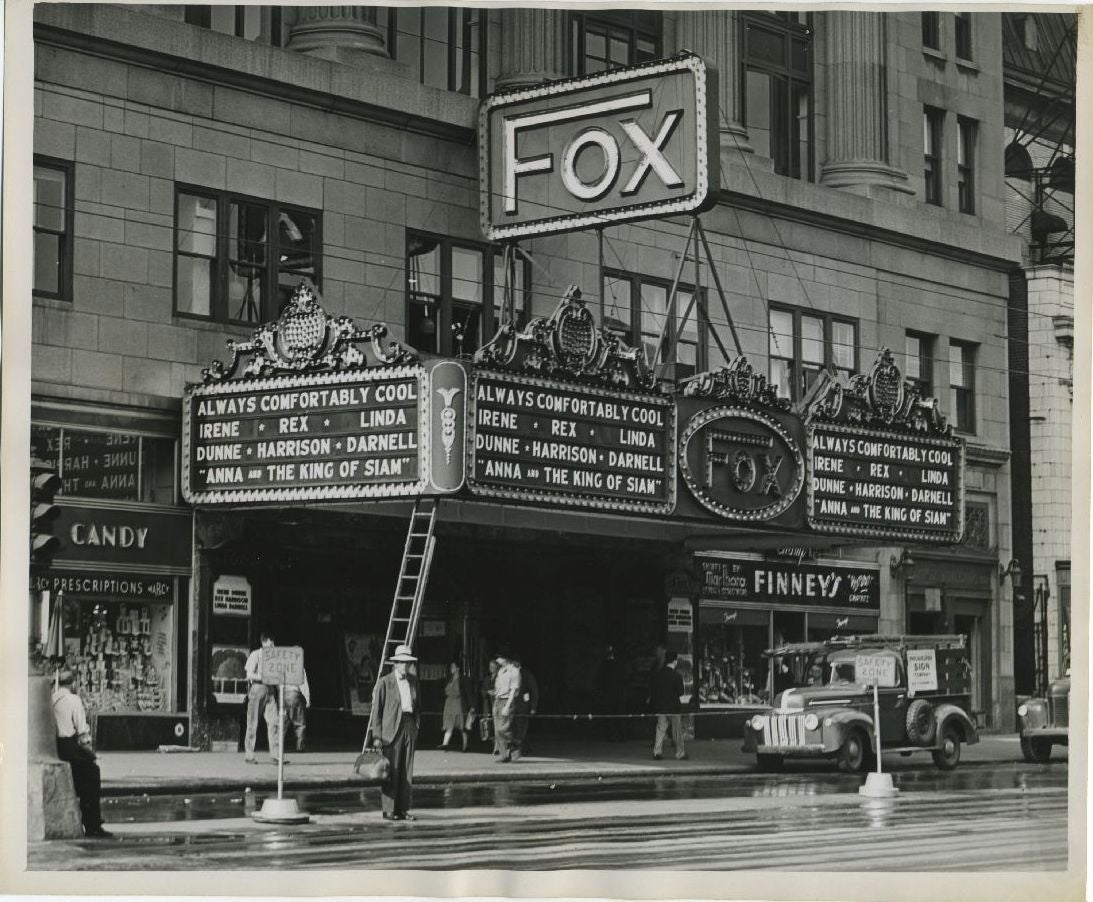

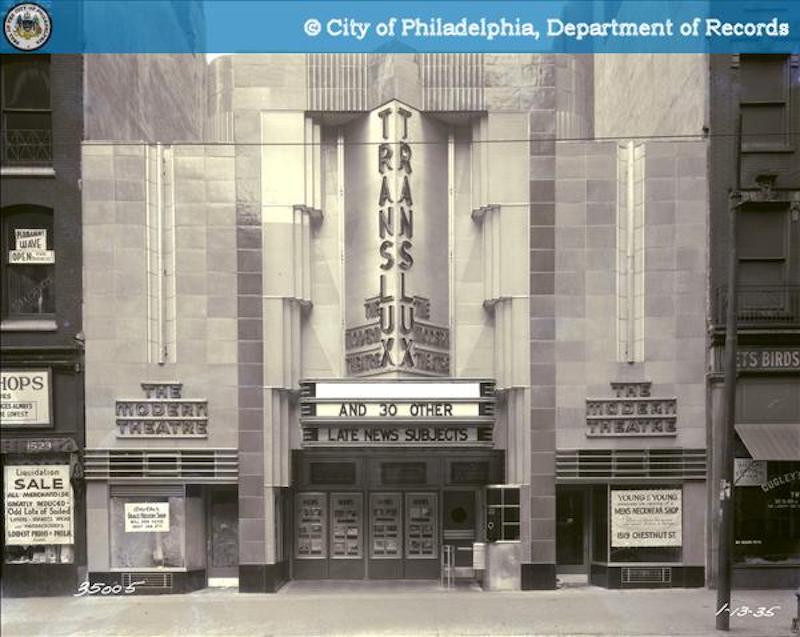

In the first half of the 20th century, towering palaces to cinema were built in Center City Philadelphia.

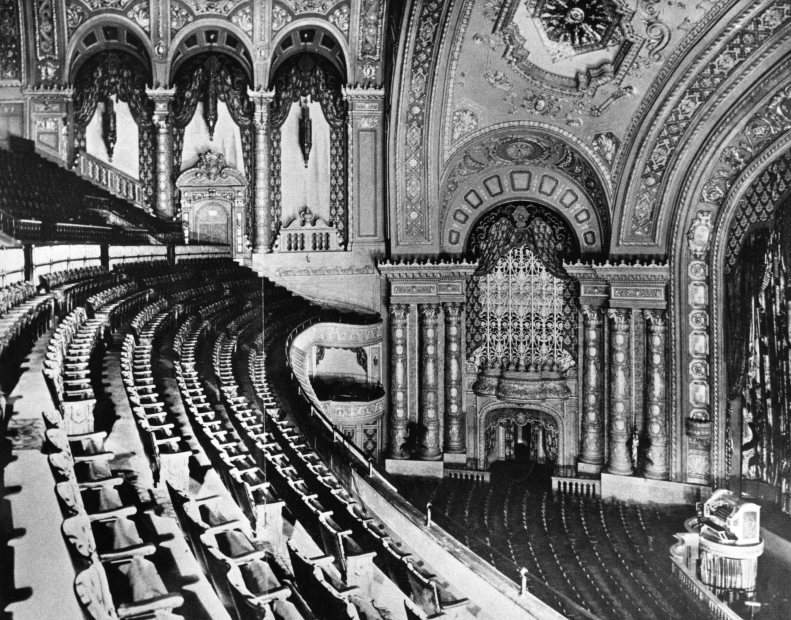

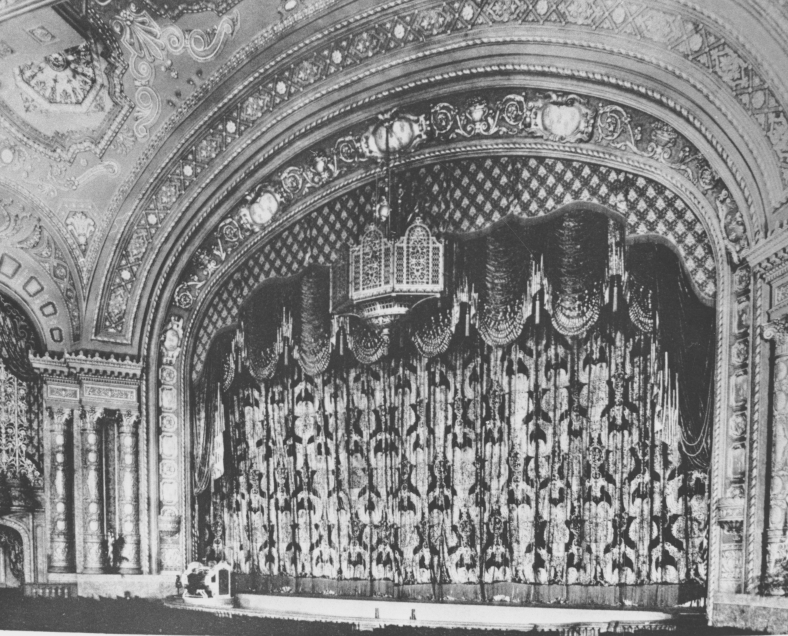

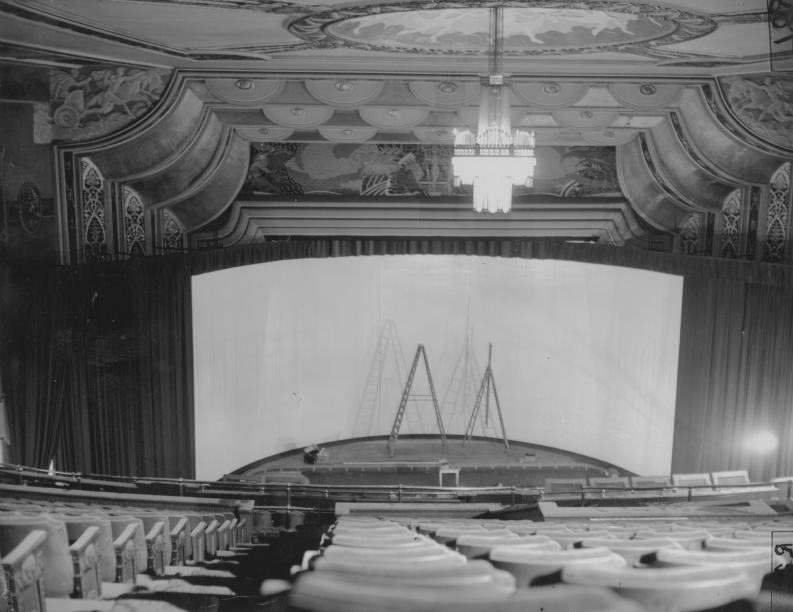

These massive buildings were ornately decorated with elaborate statues, gilded ceilings, and even orchestra pits. They lined Market Street and Chestnut Street and held movie premieres that were attended by Hollywood celebrities. The city’s neighborhoods were dotted with movie theaters too, but an outing to one of the downtown cinemas was a special occasion that required fancier dress.

As the century progressed, however, they began to close down. The pervasive popularity of TV didn’t help, but neither did the flight of middle class and wealthy people to suburbs where they could drive to new state-of-the-art theaters.

In short, the fate of central city movie palaces mirrored the decline of urban America itself.

But this year, AMC Theaters announced that the renovated Gallery mall downtown—now dubbed the Fashion District Philadelphia—would host a first run movie theater.

It will be the first full service mainstream movie theater downtown since the Boyd closed in 2002 and it provides a great excuse to reflect on the history of movie theaters in Center City.

“I think a lot of cities need to think about returning to the past as an urban model,” says Bryant Simon, a professor of history at Temple University. “The leisure world anchors of the heyday of the U.S. city were the department store and the movie theater. They offered this kind of affordable luxury that engaged people and brought them downtown.”

But it’s hard to know whether the new downtown theater can be successful in that same way. In the heyday of the movie palaces, from the late 1920s through the early 1960s, the theater offered a night of curated and affordable luxury to a mass audience.

These were spaces that were designed to cater to a broad swathe of America, just as the movies were designed to cater to an expanding (and largely white) middle class. Many theaters were also segregated in the pre-Civil Rights era, and the theaters themselves were heavily policed to tamp down on any youthful bursts of exuberance.

This model was hugely successful. Before the cultural and racial tumult of the 1960s, dozens of movie theaters blanketed downtown. They were yet another example, along with the office towers and department stores, of how Center City Philadelphia served as the nucleus of the metropolitan area.

“Center City was the anchor for the entire region,” said Howard Haas, who fought to preserve the Boyd Theater (which closed in 2002 and was demolished in 2015). “The movie palaces and the department stores were the main reasons people, from the 1920s and through the 1970s, came downtown.”

Suburbanization didn’t undermine the theaters, at first. Residents began leaving the city in large numbers during the 1950s, but still worked and played downtown. That changed as urban segregation eroded, white flight accelerated, and the crime rate began to rise.

Those social forces, paired with the ubiquity of television and the splintering of the old studio system, spelled the beginning of the end for downtown theaters.

In the 1970s, as the audience for mainstream movies fragmented, some theaters began to show pornography or art house films. Others simply closed. By the 1980s Haas estimates that 20 screens remained downtown, split between a handful of theaters. By the turn of the century only the Boyd remained.

Most of the old movie palaces have since been demolished because they are too hard to repurpose.

“There is a strong push for preservation that everyone understands,” said Paul Levy, the president of Center City District. “They were these great palaces where everyone came together. And yet market realities are very far from that today.”

A few of the old theater buildings remain. One now hosts a CVS near Rittenhouse Square. The Prince Theater still shows movies occasionally, along with a raft of other events like lectures and concerts.

“We should celebrate the architectural form of the great movie theaters of the past,” said Simon. “They offered a deeply embellished kind of a fantasy space for people. But we also have to recognize what it took to create that past: A unified popular culture, a kind of segregation, and a lot of policing.”

It is as yet unclear what the new multiplex will look like. But it is slated to have reclining seats, serve alcoholic drinks, and boast massive screens. Gilded ceilings and live music, however, are unlikely to make a comeback.

Dear reader, we will get straight to the point: Today we ask you to protect PlanPhilly’s independent, unbiased watchdog coverage. We depend on you to bring the news that you value and spread voices across the city. This holiday season, please give the gift of public and accessible media for all by making a tax-deductible donation during our once-a-year membership drive. Thank you for making us your go-to source for news on the built environment eleven years and counting.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.