For these Mormons, getting Historical Society of Pa.’s trove of records online is religious work

ListenInside its building in Center City Philadelphia, the Historical Society of Pennsylvania has records predating Philadelphia. Twenty-one million documents and 600,000 books, some dating back 350 years, cram its shelves.

The family history library, alone, has hundreds of thousands of pages and documents related to regional families. The society would like that material to be turned into digital documents that can be searched online.

The herculean task is only possible with help from the Mormons.

“The pace at which one would need to move to have a substantial number of records digitized is practically impossible,” said Page Talbott, society president and CEO. “But Family Search has developed an infrastructure that is remarkable.”

Family Search is the genealogical organization of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. What is remarkable is that the church has turned library work into a religious mission. Hundreds of thousands of Mormons around the world are volunteering their time toward a single mission: to amass the largest genealogical database in the world.

Two of them are Jerrol Syme and his wife, Margaret, from Mapleton, Utah. The church gave them two plane tickets to Philadelphia and a portable digital scanner. They will spend a year in a small corner of the society’s archives, quietly pulling family history books from the shelves and scanning each page.

They arrived in mid-August. After two months of work — seven hours a day, five days a week — they have only progressed into the B’s — for instance, an 1898 volume called “Bingham, and Other Genealogies.”

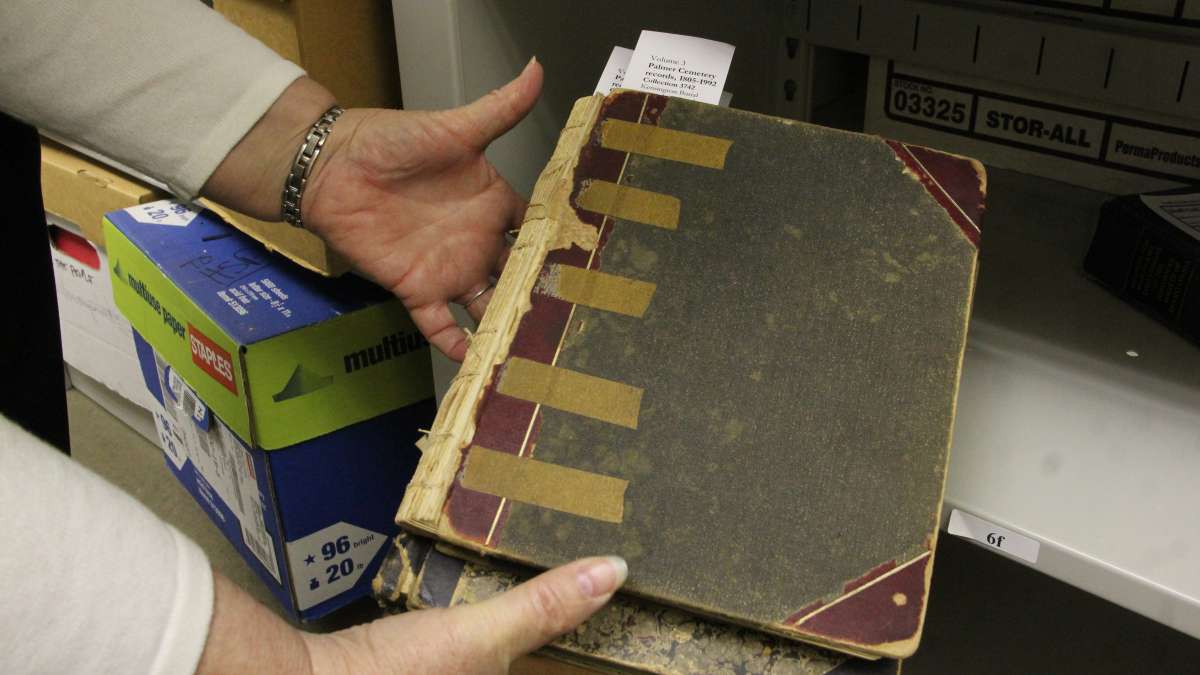

“There are pictures, information on individual people, some narrative storylines,” said Margaret Syme, manipulating the delicate pages to fit on the scanner bed. “There are foldouts of letters and documents.”

The Symes, both in their late 60s and retired, trained for three weeks in Salt Lake City to learn the software, the scanning technology, and the proper way to handle old books.

“Some are fragile. You’re turning the pages very, very slowly,” said Margaret Syme. “You can see on the floor there are little bits of paper from where edges of the pages of the books crumbled off.”

The Symes, manning one of a number of Family Search scanning centers around the world, are the front-line warriors of the campaign. They cross-check Family Search’s databases to select unique family history books — books that exist only at the Historical Society — and check for copyright restrictions.

After scanning, the digital pages go into the cloud where other Mormon missionaries use their home computers to index all the names, dates, and locations.

“I have to re-remember all the spreadsheet and Windows applications I was hoping to put in the back of my brain and never use again,” said Jerry Syme, a retired Air Force colonel who was once a nuclear missile launch officer.

The Symes left behind their house in Mapleton, their eight children and 30 grandchildren, to spend a year doing volunteer work in Philadelphia, where they know nobody. They depend on Skype, and the support of the local Mormon community, to keep them going.

The rigors of digital scanning is not so demanding that they can’t do a little digging on their own. The Symes both have Quakers in their ancestry.

“I happened to find my 12th, 11th, and 10th great-grandfathers in one of the books that we did a week ago,” said Jerrol Syme. “That’s a treasure book, it contains family members that are close to me. It’s here, and probably nowhere else.”

Twenty-five percent of the books in the Historical Society’s family history archive are unique, not existing in the Family Search database. Jerrol Syme says that trove could keep a team busy for three to five years. The Church of Latter-day Saints plans to send backup.

Talbott is looking forward to that volunteer army tackling photographs and hand-written documents, which are extremely labor-intensive to index. There are hundreds of thousands of pictures in the HSP archive, which cannot be automatically read — as printed documents can — by optical character recognition software.

“Back in the ’40s or ’50s, we received all of the photo morgue of the Philadelphia Record. In that record, there are 90,000 photographs of WWII veterans, that were sent to local newspapers to indicate training, promotions, where they were stationed, and when they were injured or died,” said Talbott. “Ninety thousand images of WWII soldiers are sitting in one of our vaults.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.