Mantua residents want to rezone their neighborhood. Does their Councilwoman?

Grace Evangelical Lutheran Church sits at the intersection of Haverford Avenue and 36th Street in West Philadelphia’s Mantua section. On June 2, over 75 people packed into the community room, with hardly an empty seat in the house. The attendees were there to vote on a plan to rezone the entire neighborhood, transforming much of it from a longstanding designation as multi-family residential to single-family residential. The vote wasn’t binding but was intended to demonstrate the neighborhood’s preference to District Councilwoman Jannie Blackwell; local community groups have been hoping to convince her of rezoning’s merits since 2014.

Emotions ran high during the community meeting. For decades Mantua has been a predominantly African American neighborhood, largely comprised of two- or three-story row houses. But as Drexel University continues growing, students are seeking housing beyond Powelton Village. In recent years, developers have been erecting three-to-four-unit apartment buildings in Mantua, many of them on the neighborhood’s abundant vacant parcels.

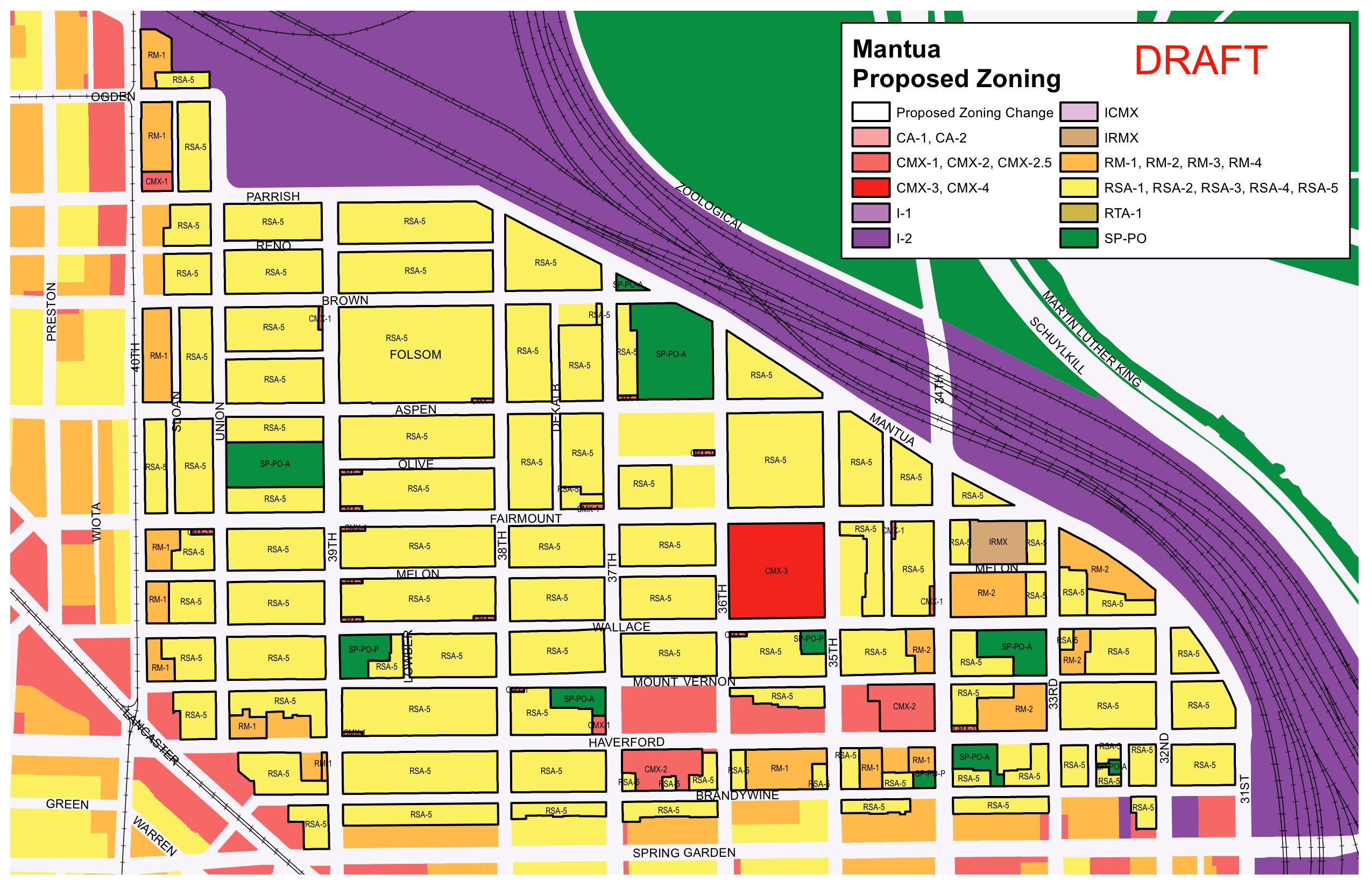

In many modest row house neighborhoods outside Center City, this kind of construction would require the Zoning Board of Adjustments to grant a variance. Not so in Mantua which, like much of the rest of West Philadelphia, retains outdated zoning. Even as much of the city is being remapped in light of the new zoning code, Mantua still has base zoning established in the 1950s when planners expected the city to continue growing beyond 2 million residents. About 92 percent of the properties in the neighborhood are zoned RM-1, which allows for relatively small-scale buildings that can be split into numerous apartments.

“When developers get the property by right, they don’t have to tell the community nothing,” said De’Wayne Drummond, president of the Mantua Civic Association, as he explained the agenda of the June 2 meeting to the crowd. “That is why things are popping up and we don’t have a clue about it…This doesn’t mean we want development to stop, it just means we want to sit at the table with our future neighbors. We want to let them know we are a community and that we do have a voice.”

Mantua is a small neighborhood bounded by 40th Street to the west, Spring Garden to the south, with railroad tracks and the Schuylkill River to the north and east. The two Census tracts that largely comprise the area have experienced a 66.8 percent decrease in population between 1960 and 2013.

Today about 5,594 people live in this sliver of West Philadelphia, but the neighborhood remains very active and boasts many community groups. Three of these, the Mantua Civic Association, the Mt. Vernon Manor CDC, and the Mantua Area Improvement Committee are championing the rezoning effort. They have been pressing their case for a year and a half.

The entire proposal hinges on Councilwoman Jannie Blackwell. The Philadelphia City Planning Commission has drawn up legislation that would dramatically change how Mantua is zoned, as specified by the demands of the community groups. City Council must pass legislation in order to rezone the neighborhood. The neighborhood is in Blackwell’s district, and according to the customs of the legislative body, she must be the one to introduce the bill.

“We brought it to you [Blackwell] assuming you would know what to do, because everyone believes that she is the most powerful woman in the city,” says Michael Thorpe, executive director of Mt. Vernon Manor CDC in an interview with PlanPhilly. “You bring it to her and you expect her to advance it, to do what it is that you want done. But you have to help, work with her, tell her what it is you want to do. And then ask her to be accountable. That’s what this process is now.”

At a late April meeting held to demonstrate neighborhood support for the remapping, Councilwoman Blackwell appeared concerned about several issues raised by constituents. Some in the crowd feared the remapping would impede their ability to subdivide their homes. Blackwell assured them it wouldn’t, but planning commission representatives present at the meeting disagreed. The councilwoman expressed reservations about the “downsides” of rezoning, and left the meeting without giving assent to the plan. She did promise to do what the community desired, but left before a hand vote showed unanimous consent for it.

“I believe at that time there wasn’t a yes but there wasn’t a no,” says Drummond in an interview with PlanPhilly. But the community groups decided that an educational campaign was needed to ensure that there wouldn’t be any confusion the next time Blackwell came out. Last Thursday’s meeting took place as part of the effort to show a united front in support of the remapping.

“Zoning can be complex,” says Drummond. “We are doing zoning education awareness meetings so we can tell you about single-family dwellings versus multi-use. What does it mean and what would it look on your block?”

Last Thursday’s meeting also gave the councilwoman a chance to ask more questions about the process in public. Blackwell used the occasion to pepper the representatives of the Planning Commission with inquiries. She opened by noting, to laughter from the room, “Anyone who doesn’t tell the truth gets a beating.”

Blackwell’s line of questioning focused on whether her constituents’ houses could be split into apartments for family members without a trip to the zoning board under the new plan. (The answer is yes, as long as there isn’t a separate entrance for the other resident’s unit.) Blackwell shared anecdotes about her own experiences as a homeowner in West Philadelphia and the hassles that came with having a house that had been carved into numerous apartments. Most of her points were not related to zoning, but to issues with the Department of License and Inspections and taxation rates.

“My house with Lu in University City is near 45th and Spruce, and a lot of people on the block rent out rooms and make plenty of money,” said Blackwell, referring to the house she moved into when she married former councilman Lucien Blackwell. “Now Lu had children when I married him, so I told the city it was family on the third floor, even though they had a couple bathrooms, kitchen, and everything. So I had a problem because they wanted to charge me more like I was renting, but I wasn’t. The kids had just grown up and moved out.”

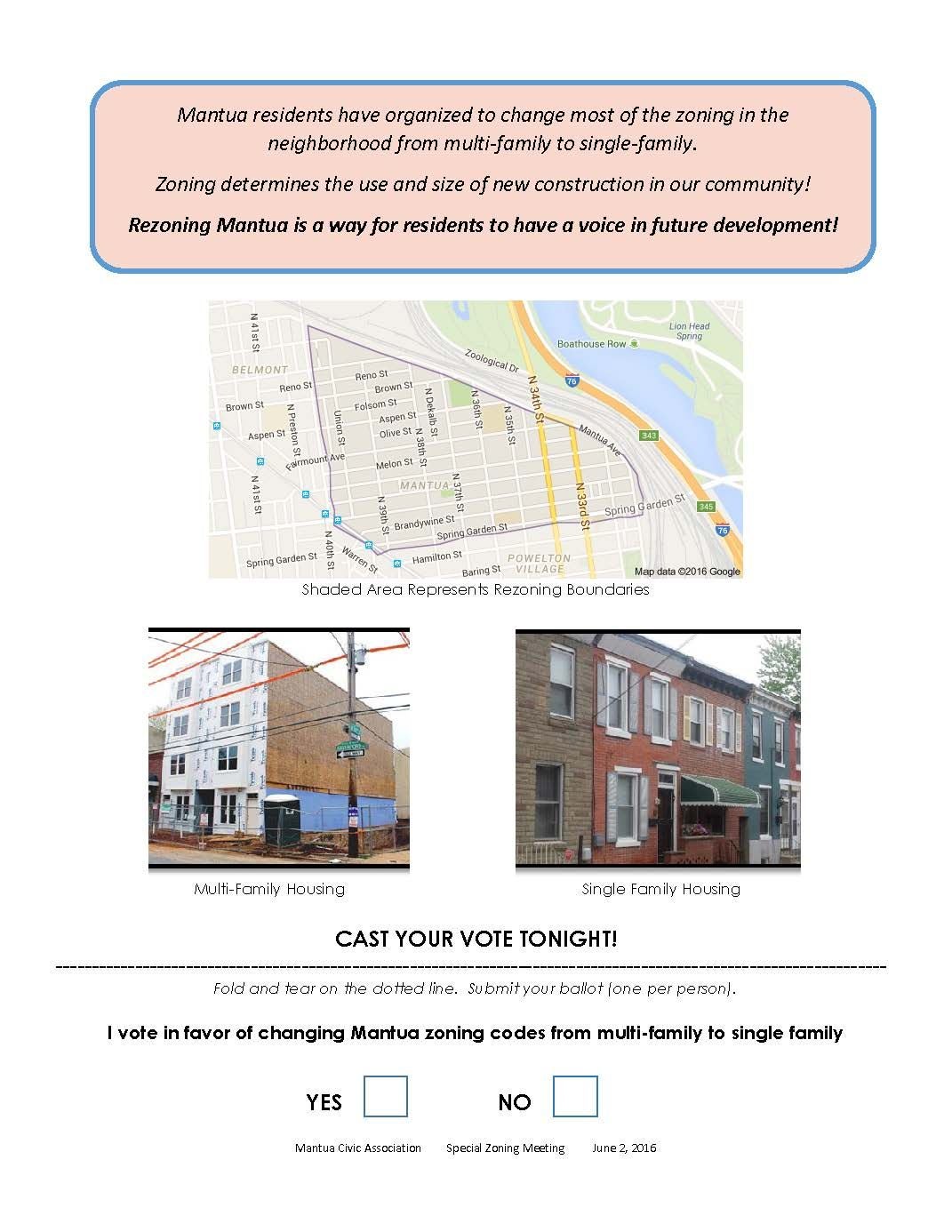

After Blackwell’s round of questions, ballots were handed out by the community groups with simple “yes” or “no” options on the proposed remapping. Even these slips of paper were part of the education campaign, offering images of a small apartment building under construction versus a row of two-story houses to illustrate the issue at stake. The tables where attendees sat were hedged in by three sets of maps, displaying the current zoning and what the remapping proponents hoped to make the neighborhood look like.

The room dissolved into conversation, much of it regarding escalating housing costs in Mantua. Many attendees attributed the new construction to their increased property taxes and other housing-related bills.

“All the elders have up and died, now it’s a whole block of students,” says Margaret James, who has lived in Mantua for over 50 years and has seen her street change dramatically. “If they build those houses, what happens to my taxes? I’m a senior with a fixed income. It’s terrible! But I’m not leaving. They’ll have to carry me out.”

The room buzzed with fears about displacement and the pace of change. “It’s all about what they can conquer,” says one of James’ neighbors. When the time came for the vote, 63 ballots were in favor of the remapping with 9 opposed (and one abstention). The crowd broke into loud cheers when the final tally was counted out, although Blackwell was not present to hear it.

An overhaul of Mantua’s zoning was initially proposed back in 2014. The proposal would put the neighborhood on a similar footing as rowhouse sections of the River Wards, South Philly, and North Philly, where sections have been rezoned from multi-family to single-family classifications.

At the June 2 meeting, Drummond and Thorpe expressed a hope that Blackwell will introduce remapping legislation this week or next week, before City Council recesses for the summer. But there is little time before the end of the session for the necessary hearings. In all likelihood, the community groups of Mantua will have to wait until the fall.

Until Blackwell does introduce the legislation, Mantua is ripe for new low-rise student-oriented housing, which developers won’t have to ask the zoning board to approve or neighbors to support. Much of this new construction is concentrated in the eastern section of the neighborhood, and is still comprised of row house-type structures that are typically taller than most of the neighborhood’s older homes. These can be distinguished by greater height, numerous mail boxes and, of late, Bernie Sanders campaign signs in the windows.

On the 3400 block of Brandywine, about half the buildings on the narrow street are relatively recent additions. For longtime resident Darnell Mears, seated on the porch of a two-story red brick row house, the changes have been a mixed blessing.

“Before it was just some lots and scraggly buildings,” says Mears, who was born in the 1940s and remembers when the area was still racially mixed after the war. “When they [the new houses] went up my taxes went up. Everything is high now. But I bought this house cheap and I’ve been here 30 years. It’s [the block] changed a lot since then, for the better. You can’t complain, except when the students have parties.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.