American watercolor paintings finally getting respect

Most people – perhaps every person who had ever been exposed to art as a child – knows watercolor. Inexpensive and accessible, it is the most popular gateway medium into artmaking.

Next week, the Philadelphia Museum of Art will open an exhibition (March 1-May 14) about a moment when the humble watercolor rose from amateur hobby to the vanguard of high art.

For the longest time, watercolor artists could roughly be separated into two camps: women who dabbled at home, and commercial illustrators and draftsman making technical drawings.

But in 1866 the American Watercolor Society was founded. It aggressively recruited all these overlooked people on the fringes of American art.

“They were always disadvantaged in a general art exhibition, because their work was lighter and more delicate, and didn’t come off well,” said curator Kathleen Foster. “They got second-class treatment in the big exhibitions. So by creating their own exhibition forum where they could shine and make stars of their own…They could suddenly step up and say, ‘Oh, I have some work to show.'”

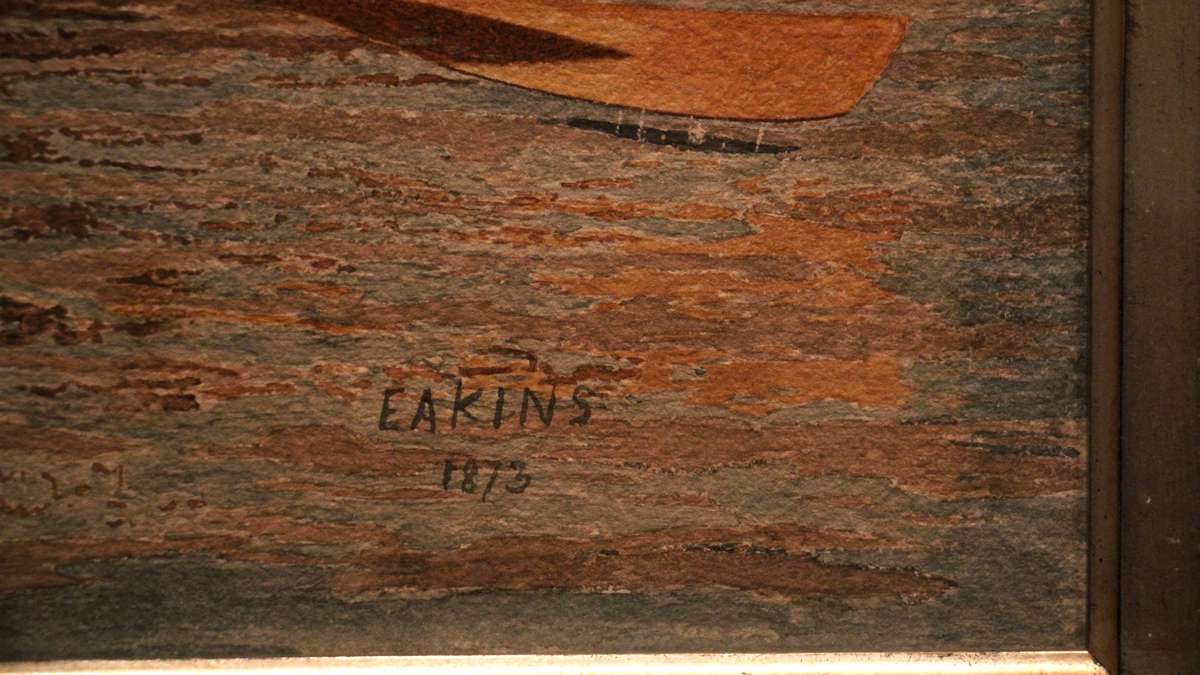

Foster had been working on “American Watercolor in the Age of Homer and Sargent” for five years. It took so long because people who own watercolors are loathe to loan them out for fear too much light exposure will fade their delicate colors. Indeed, a watercolor of a Schuylkill River rower by Thomas Eakins is visibly faded in its center, compared to its darker edges; that painting is hung behind a curtain to hide it from too much light.

Foster has really been working on this for over 40 years, since she discovered in grad school this moment in art history when, very suddenly, the lowly watercolor became the centerpiece of American art.

The society strong-armed watercolors into American culture, making them not just popular but lucrative. That’s when major artists like Winslow Homer, John Singer Sargent, and Thomas Eakins jumped in, turning the fabricated phenomenon into a bona fide American art movement.

Watercolor was fighting against oil paint, long considered the medium of choice of high art. Oils are more robust and versatile, but the delicacy of watercolor can create an effect that is elusive to oils.

“What watercolor has is its luminosity,” said Foster. “If you work on white paper and use transparent tints, you get a high value from the paper. You’re going to get light bouncing back at you from the paper. That’s what you get in Homer and Sargent. It gives a sense of luminosity you can’t get in oil paint.”

With 175 works, the show is a comprehensive overview of American watercolor at the birth of modernism. Foster takes care to parse out mini-movements within the rise of watercolor, as the pendulum swung from natural realism (which proved exhausting for both artists and critics) to the looser influence of impressionism.

The work ranges from purely decorative beauty of flowers, to rugged American landscapes and seascapes, to nostalgic figurative work, to the extraordinary domestic scenes by Edwin Austin Abbey, one of the most sought-after watercolor artists of his day (1852-1911) whose works on paper are rarely seen anymore. “They are all in the basement of Yale University,” said Foster.

Many of the pieces in “American Watercolor” are rarely, if ever, seen publicly. For the conservation of the artwork, the show will not travel to other museums; it can only be seen in Philadelphia, and only until the end of May.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.