Land Bank revises targets in 2017 strategic plan

“We are seeing first hand why the land bank may not be as efficient as it could be,” Aviva Kapust, executive director of the Village of Arts and Humanities, told the Philadelphia Land Bank board in a public hearing on January 5. “Two days ago, we were informed that two of our properties in the middle of the art park, two of those privately-owned tax delinquent parcels which were meant to not be on the Sheriff’s Sale list were mistakenly added to it. And they were purchased.”

Kapust is well aware of the dangers vacancy holds and the racist public policies that spawned it. Over the last several decades the Village transformed vacant lots and abandoned buildings in North Philadelphia into a string of art parks to mitigate the damage.

The Philadelphia Land Bank is designed to cut through the kind of complex legalities that bind much of the vacant land her organization occupies. The land bank promises to rationalize the vagaries of the city’s land sale process, prioritize different uses, and put vacant property back to productive use.

After Kapust spoke with land bank representatives, two properties occupied by the Village were removed from Sheriff’s Sale and placed at the top of the Land Bank’s acquisitions list, with the intention that they would be transferred to the organization for a nominal fee. Rather than being able to celebrate that triumph, Kapust was motivated to testify before the Land Bank board because these properties were not held out of the Sheriff’s Sale process.

In telling her story, an audible gasp could be heard in the overstuffed hearing room. Stories like Kapust’s are the exact kinds of chaotic and confusing situations that the land bank is supposed to do away with.

No one ever said reforming Philadelphia’s land sale policies would be easy. But in the three years since the creation of the land bank under Mayor Michael Nutter, and a year into Mayor Jim Kenney’s tenure, the Land Bank is still haunted by serious questions even from longtime supporters like Kapust.

Late last week, the Kenney administration’s updated strategic plan received the approval of the land bank’s board. The plan is slated to go before City Council on Thursday.

The plan is studded with maps of Philly’s publicly held land and which areas of the city suffer from affordability issues or lack of access to green space. It lays out a broad set of goals—primarily eliminating blight in strong markets, fostering new housing of all types—and then outlines three possible strategies to fulfill those goals. The most modest plan won out: obtaining 269 properties for acquisition this year and eventually building to 2,650 over the next five years.

The first draft of the annual plan dropped the week before Christmas and the public hearing for comment that Kapust attended occurred on January 5. But some advocates questioned the need for a new document at all.

The Land Bank ordinance requires an annual strategic plan. It doesn’t necessarily require a new one though. The initial plan, which advocates praised, dated to 2014 when it was put together with Interface Studio, a local planning firm. In 2015, the board simply decided to re-adopt that 2014 strategic plan.

The administration argues that they couldn’t do the same again this year because circumstances have changed due, in part, to the transfer of over 1,600 properties into the land bank from other public agencies since the beginning of Kenney’s term. The first acquisitions also included privately held tax-delinquent properties. The acquisitions allowed agency to set exact goals for disposition the first time since its creation. The agency is moving forward, the city’s argument goes, and it needs an updated strategic plan to guide it.

At the overflowing January 5 hearing Kapust was among the community representatives, affordable housing activists, and urban agriculture advocates who offered carefully constructive criticism of the new strategic plan.

The issue of affordable housing got a vigorous airing at the early January hearing, in part because the Philadelphia Coalition for Affordable Communities packed the conference room. Many of their coalition members wore brightly colored shirts and offered moving testimony about the difficulty of finding affordable housing in their neighborhoods.

When coalition leader Nora Lichtash spoke, she first praised the plan for setting specific goals for the acquisition and disposition of land. She just took issue with the content of those goals, which she argued didn’t do enough for most of the residents in America’s poorest city with over a million residents.

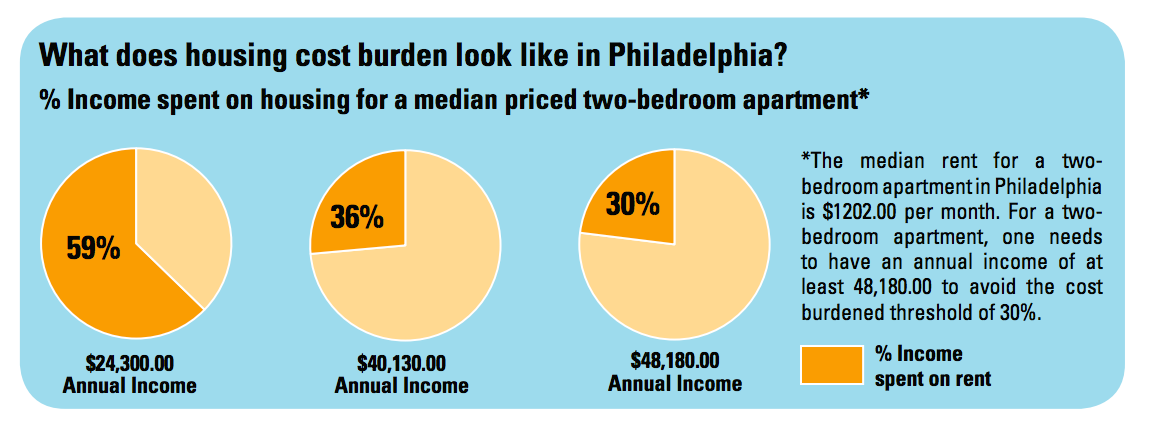

In the first draft of this year’s plan, only 10 percent of the housing target was aimed at the poorest renters—those making 30 percent or less of area median income (AMI), or $24,000 for a household of four—while 60 percent were targeted towards either market rate or “affordable housing” for those making over 60 percent of AMI (therefore substantially higher than the city’s median income).

“This distribution in this draft plan is not fair nor is it equitable,” said Lichtash at the hearing. “Those who develop real estate know, developers will build to the upper end of income targets, so what we see in the plan is that 90% of the properties will be conveyed for homes that meet the needs of wealthier residents, and only 10% or 10 tax delinquent properties will be developed to be affordable for Philadelphians who earn the median income.”

She focused on the 70 properties to be sold the first year, requesting that half be slated for housing affordable to those who make the city’s median income or less.

Open space advocates, meanwhile, expressed concerns about the lack of specificity around goals for greening in the strategic plan.

“The new land bank strategic plan details careful analysis of the market context and subsequent need for affordable housing, market-rate housing, and economic development,” said Amy Laura Cahn, of the Public Interest Law Center, in her testimony before the board. “However, unlike the prior five-year Land Bank Strategic Plan, this plan does not apply the same attention to the need for and impact of urban agriculture, gardens, and open space, nor does it set out a plan to achieve the stated goals of increasing and preserving these spaces.”

Both of these critiques influenced the final plan. In the updated draft, the disposition policies were altered at the behest of open space advocates, with the five-year cap on leases removed and now there is a one-time application fee per lease rather than a yearly parcel fee. Additional acknowledgment of open space needs were included earlier in the report, a map showing access to open space got front-loaded, and one on walkable access to healthy food was added to provide a parity with discussion of affordable housing.

In the revisited draft, the percentage targets for affordable housing in the five-year proposal were made more generous for those earning below 30 percent of the area median income, median income, now set at a 20 percent target at the expense of workforce housing (for those at 120 percent of AMI) and market rate housing, which were reduced from 30 percent to 25 percent.

As for Lichtash’s more specific critique about the immediate future, the next full year target – for the 2017-2018 fiscal year – the number of units for those making 30 percent or less of AMI increased from 10 to 41. “I think that the land bank board shifted the plan based on our coalition’s strong testimony,” says Lichtash. “It feels like a win.”

Several unanswered questions still loom large, however. Advocates pressed the board to set more ambitious acquisition goals when it comes to privately held tax-delinquent properties. The previous strategic plan from 2014 included escalating targets for acquisition of tax delinquent properties, ramping up to 500 such foreclosures by year two (2016) and ending with year five (2,000 foreclosures). The new plan reduces the acquisition target to 325 annually for the five years in question, leading to a greatly reduced total.

Acquiring land at a steadier clip could potentially help with the land bank’s bottom line, which could be important, as there isn’t much of a dedicated source of revenue right now. (Although acquiring new properties comes with processing and maintenance costs too.) Instead, different lines of funding have been stitched together from year to year, but

now that the agency’s about to begin selling land, these other forms of funding are receding. In fiscal year 2017, the land bank’s budget is $700,000 smaller than the year before because the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority (PRA) is providing almost $2 million less than it did in fiscal year 2016.

The new funding in the 2017 budget comes from city property sales, providing $1.2 million, while the city’s contribution from general funds remains the steady at $500,000.

“I want to encourage the Kenney administration to adequately fund the land bank,” said Winnie Branton, a consultant and author of the Pennsylvania land bank guide, at the January 5 hearing. “You’ve done a great job getting properties into the land bank, now they are sitting there waiting to be transferred out and that needs money and resources.”

The strategic plan seems to confirm that with the current funding available the land bank will have to be conservative in its outlook. The document lays out three possible futures for the agency and then settles on the least ambitious (and the only one that wouldn’t require the budget to more than double).

With progress advancing so slowly, it seems likely that most tax-delinquent properties will continue to fester and, occasionally be sold at Sheriff’s Sale. That process leaves much to be desired: The final draft reports that just 12 percent of properties dispensed through Sheriff’s Sale ever actually have building permits issued for them. Just three percent have certificates of occupancy issued.

The Village of Arts and Humanities has a good chance of winning a happy ending for the two properties mistakenly sold, at least. Kapust is working with pro bono lawyers at Reed Smith who are helping her organization acquire the parcels. A judge granted their petition to stay the sale, but the case is not yet resolved. She’s in in touch with her local councilperson and the staff of the land bank. But she knows most people aren’t as politically savvy as she is and they may not be able to fight back when an investor at Sheriff’s Sale snaps up a property they’ve maintained and cultivated. That’s why she believes the land bank needs to fulfill its original promise.

“We really appreciate the land bank staffers who are working to ensure those properties do not fall into the hands of the speculators,” said Kapust. “But this is still really worrisome because not all of the organizations and individuals we are working with have the capacity to remedy the situation as swiftly as we hope we are doing right now.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.