Joys and realities of black life in Philadelphia chronicled in Mosley photos at Woodmere

As Philadelphia’s African-Americans struggled for justice and civil rights in the early 20th century, they also went to the theater, took vacations at the Jersey Shore, owned businesses, ran track, and waltzed at formal balls.

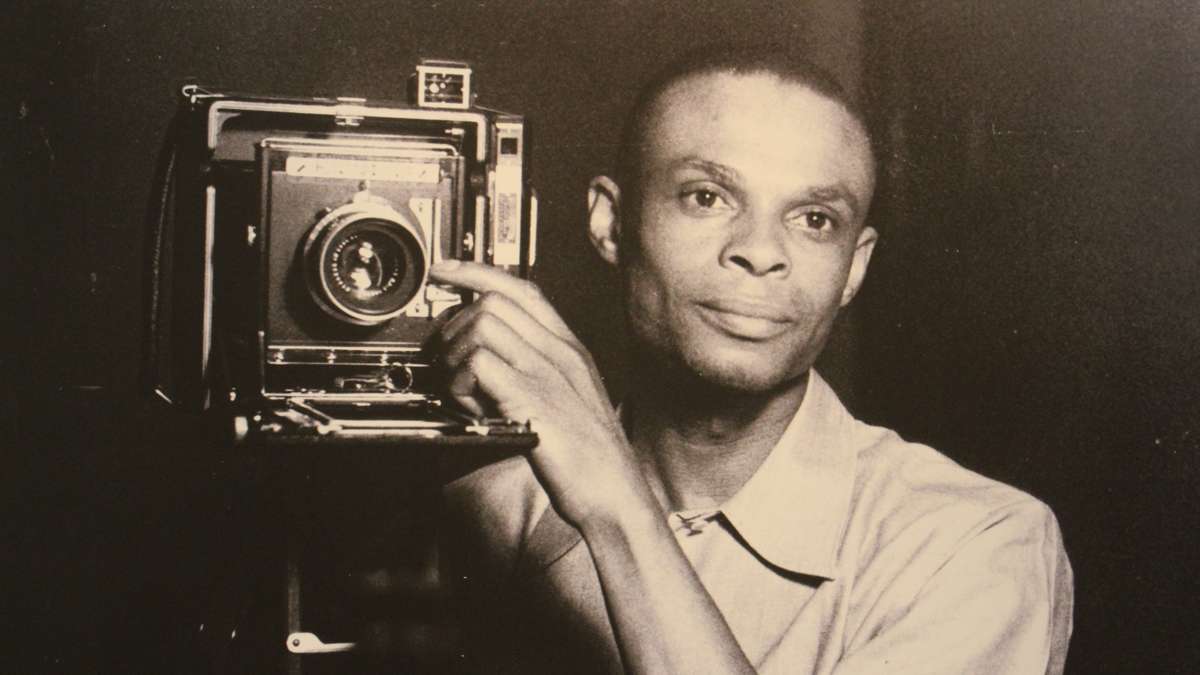

That view of black Philadelphia — an aspirational, middle-class view — was captured by visionary photojournalist John Mosley. The Woodmere Art Museum in Chestnut Hill now has on view “A Million Faces: The Photography of John W. Mosley,” featuring selections of his prolific output.

Mosley was a quiet, unassuming man who doggedly photographed Philadelphia for three decades — from the 1930s to the 1960s — amassing more than 300,000 images. He worked mostly for black newspapers, crisscrossing the city on public transit and recording images such as integrated athletes at the Penn Relays, Nat King Cole and a very young Eartha Kitt playing in jazz clubs, and opera lovers leaving the Academy of Music.

“There are no car crashes, there is no violence, there is no abject poverty,” said Bill Valerio, Woodmere director and CEO. “It is a joyous view of black life in Philadelphia and a view of the realities of black life in Philadelphia. This is segregated Philadelphia. This is the black-only entrance to the Academy of Music, and also amazing places like Chicken Bone Beach.”

Chicken Bone Beach was the black section Atlantic City’s seaside where Mosley often photographed African-American families at leisure, relaxing on the sand and playing in the surf. The show at the Woodmere Museum is the first time many of these images have ever been hung on a wall. They were meant to be published in newspapers, then thrown away.

Valerio only discovered Mosley while the Woodmere was researching a previous show, “We Speak: Black Artists in Philadelphia 1920s-1970s,” on view last year. Woodmere curators combed through photo archives to find images that would illustrate the lives of Philadelphia artists. Photographs by Mosley kept surfacing.

Mosley seemed to be everywhere — in artist studios, in opera halls, in neighborhood businesses, athletic fields, jazz clubs, and down the Shore. While hustling photographs for newspapers, he was also employed by the Pyramid Club, a major African-American club that established a black social class in Philadelphia. He had access to Marian Anderson at the moment she embraced Grace Kelly, he was with Joe Louis countless times, he was at Lincoln University while Albert Einstein taught black students physics.

The 300,000-strong archive is held at Temple University’s Charles Blockson Afro-American Collection. Blockson, the prominent collector of African-American books and objects who acquired the Mosley collection from Mosley’s family after his death, is featured in the archive. An image of Blockson throwing shot put in the Penn Relays as a college student is testament to the notion that Mosley would take a pictures of literally anyone.

Mosley spent 30 years building a positive image of African-Americans, countering the predominate view at the time, said Diane Turner, Blockson Collection curator.

“He was very quietly taking very realistic images of African-Americans, where they could actually see themselves, instead of the very exaggerated stereotypes that popped up in the media or popular culture,” said Turner.

Mosley’s images are often called upon to illustrate Philadelphia history, she said, but rarely are the images assembled to celebrate the photographer, himself.

Many of the images are archived with little supporting information — the who, what, and where are often unknown. The Woodmere is asking for the public’s help. All the images in the exhibition are available online, where users are able to offer feedback, insight, and memories of what is depicted in the photographs.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.