Journalist and former S. Philly High student recall 2009 attacks against Asian teens

WHYY’s `Morning Edition’ host Jennifer Lynn discusses a Chalkbeat retrospective on the bias and violence that spurred a student boycott.

Listen 6:35

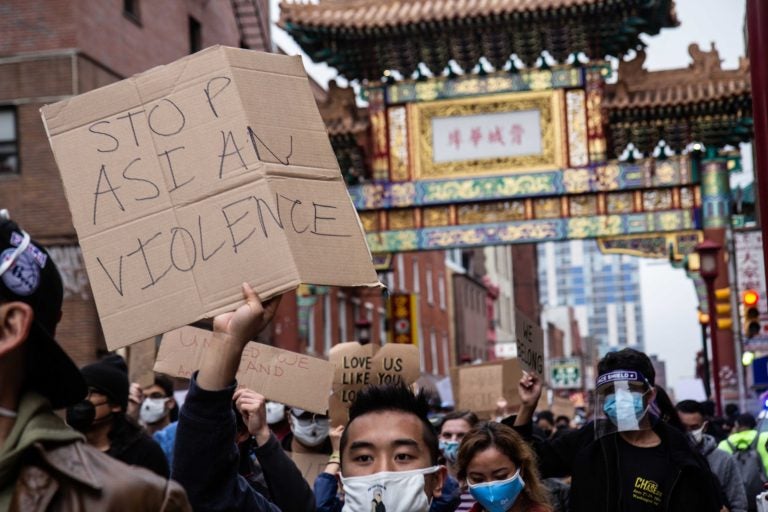

Philadelphians gathered on 10th street in Chinatown for a solidarity rally and march against violence directed at Asian Americans on March 25, 2021. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

This month, the federal COVID-19 Hate Crimes Act sailed through the U.S. Senate. The bill addresses rising race-based violence against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders during the pandemic.

Anti-Asian behavior is not new in Philadelphia.

A retrospective published online in the education journal Chalkbeat takes us back to December 2009, when racial tension came to a head and more than two dozen Asian students were attacked inside and outside South Philadelphia High School by a group of mostly Black students.

When school leadership denied anything had happened, some of the Asian students staged a boycott and drew up a list of demands to ensure their safety.

Reporter Dale Mezzacappa wrote the retrospective. Bach Tong participated in the boycott. He was 16 at the time. He and his family had just moved to Philadelphia from Vietnam.

Morning Edition host Jennifer Lynn spoke to Mezzacappa and Tong about that tense time and what transpired.

—

Bach, what was it like for you at South Philadelphia High School in 2009?

Bach: I remember feeling unsafe the majority of the time I was in school. I remember feeling afraid for my safety to go into the hallway, to the bathroom, to the lunchroom. I remember not knowing what exactly to do. And a lot of my classmates who were attacked or who experienced, like, violence did not really have a resolve from the school administration.

You’ve described finding safety on the second floor of the school, where the English as a Second Language programs were. There, ESL teachers were supportive, but elsewhere in the building, staff didn’t seem to recognize how antagonistic they were toward you and other Asian students. What’s an example of that?

Bach: I remember going to the lunchroom and a staff member asked me to say a name of a food item that I was pointing to. And I was just coming to the country. I had no idea how to say the name. I didn’t even know what it was. I just wanted, you know, my lunch. Staff, they all laugh at what I said. And that happened more than once. And this happened not just to me, but to all the friends that I knew. And over time, we felt like we were not supported by the school.

Dale: Jennifer, if I could just sort of maybe crystallize something a little.

Sure. Yes. Let’s bring you in, Dale.

Dale: The level of insensitivity was so great that if a student had a complaint or wanted to report an incident, they were not allowed to make a report in their native language. It had to be in English, and they didn’t know how to do that. This is something that it was the adults’ responsibility to try to help the students deal with, this ethnic conflict and understand better. That’s what education means. And they were unable to do it.

Yeah. Bach, when you think of the students clashing, why do you think they clashed so much? I mean, you all lived in the same neighborhood.

Bach: Yeah, we all go to the same grocery store. We all took the same bus. We walked the same route to school. And we live in the same level of poverty. We all go to the same federally qualified health clinics. But then again, there was no part of the school where we all came together to really create dialogues and build a relationship, our community among students.

Dale, you wrote eloquently about this in the retrospective.

Dale: As Bach has said, and I call it in the story, the “peculiar American institution of the urban high school,” where students who need the most from all backgrounds are thrown together and given the least, and not in an atmosphere where they are encouraged and guided and nurtured to learn about each other’s cultures and deal with what they have in common, which, as Bach points out, is poverty and oppression in the American system.

All of this leads to the student boycott in December of 2009 that followed the big targeted attack on Asian students by other students at the school, some of whom felt Asian students were getting special resources to learn English and such. Bach, you and other Asian students left class. What did you do?

Bach: Every day for about two weeks, we, instead of going to school, went to Chinatown. We met, we documented our story. We documented what happened because there was nothing on the official school side that, you know, really values our perspective, our experience, or really cared about what happened to us. They, in fact, denied that it happened to us. So we felt like the only strength that we have was in our stories.

The boycott was covered in the media locally and nationally. It ultimately led to a landmark civil rights complaint. How did that frame the issue of these students wanting to be safe and to get an education, Dale?

Dale: It framed the issue in terms of civil rights being violated. And once that ruling is made, the institution is then required to change. And part of that was the adoption by the school district of an anti-bullying, anti-harassment policy, which laid out a procedure and a process for reporting such incidents and dealing with them. It was done within the student code of conduct. So it was discipline against students who violated the policy and restitution of some kind for the students who were the victims of it.

Bach, did you think the boycott and organizing students to tell their stories would lead to this?

Bach: No, you know, I was 16. I did not imagine that our organizing effort would have led to a landmark civil case recognized by the DOJ [Department of Justice]. All we wanted was to go to school in a safe place. You know, that’s really all we wanted.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.