John Dean plumbs the noxious Nixon legacy

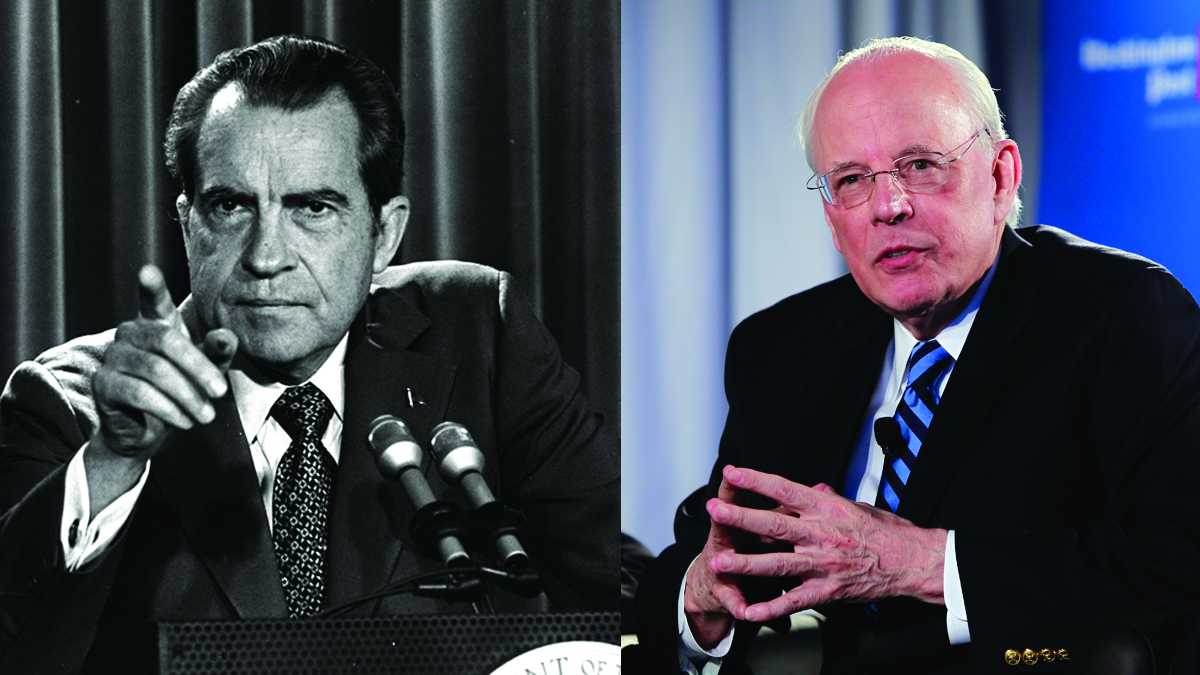

President Nixon pictured here in this March 15, 1973, file photo, and John Dean (right), White House counsel to President Nixon, on Monday, June 11, 2012 (Charles Tasnadi and Alex Brandon/AP Photos)

What better way to mark the 40th anniversary of Richard Nixon’s resignation than to hear from the White House guy who blew the whistle?

The other night, at the Philadelphia Free Library, I introduced John Dean – the former Nixon counsel who has since authored 11 books, the latest of which is a meticulous Watergate narrative culled from 1000 previously overlooked conversations captured on the White House tapes. Dean drew a huge Philadelphia audience, thankfully so, because I’d feared that few people cared anymore about Nixon’s unprecedented war on democracy.

Memo to the amnesiacs and the historically ignorant: Nixon ran a far-flung criminal enterprise that landed 40 aides in jail (including Dean, briefly). Long before the ’72 burglary at Democratic headquarters in the Watergate office building (broadly sanctioned by Nixon’s attorney general), Nixon was already warring on his opponents, by ordering illegal wiretaps, burglaries, mail intercepts, and sabotage.

In the words of authoritative Watergate historian Stanley Kutler, Watergate was – and remains – “the most significant constitutional challenge in this country since the Civil War.”

Nixon’s so-called “Plumbers Unit” burglarized the offices of Daniel Ellsberg’s psychiatrist, in the hopes of getting dirt on the guy who leaked the Pentagon Papers. (Nixon’s ’71 directive, caught on tape: “You can’t let the Jew steal that stuff and get away with it.”) He ordered another burglary by saying, “I want it implemented on a thievery basis.” And just six days after the Watergate burglars got caught in the act, he launched the obstruction-of-justice cover-up from inside the Oval Office (as captured on the “smoking-gun” tape that ultimately led to his resignation, on the eve of the Articles of Impeachment.)

Suffice it to say that if Barack Obama ever tried to do even a fraction of what Nixon did, the heads of conservatives and trolls would spontaneously detonate.

John Dean, at age 75, is most fascinated about the Watergate cover-up, about why such a savvy politician like Nixon would choose to dig a deep bunker with no exit. He says that he still wanted to “understand.” So with the help of some workaholic grad students, he plumbed the White House tapes, a multi-year project that ran to 4,000,000 words. He says the work was “very tedious…Had I known when I started, I don’t think I would’ve undertaken what I did.”

But what little gems he unearthed!

For instance, in early March ’73, Nixon worked a deal to funnel hush money to the jailed Watergate burglars, to ensure that they didn’t spill the beans about their administration ties. It went down like this: Henry Tasca, the U.S. ambassador to Greece, wanted to keep his job. Tasca’s good friend, oil mogul Tom Pappas, offered to pay the burglars if Nixon agreed to retain Tasca. Bingo.

Dean explained the deal to his Philadelphia audience by playing key tapes on the sound system. Nixon aide H. R. Haldeman told his boss, “You might as well get your chits out of him (Pappas),” by agreeing to retain Tasca. Nixon then met with Pappas and praised the oil mogul’s willingness “to help out.” He also told Pappas, “A few pipsqueaks down the line did some silly things…nobody in the White House is involved” (which itself was a lie).

Two weeks after the cover-up session with Pappas, Nixon sat with Dean, his White House counsel. Dean now says, “I think this was the first meeting where I really met Richard Nixon” – as in, the real Nixon. At that meeting, Dean warned the president that “cancer” was growing on the presidency, that the cover-up would not hold. But Nixon acted as if he was hearing about a cover-up for the first time; in Dean’s words now, “he played dumb for me, (like) he didn’t know any of it.”

Dean said it would probably cost a million bucks to ensure the Watergate burglars’ silence (Dean recalls that he pulled that figure “out of thin air”), yet Nixon responded – on a tape played for the audience – “We could get that. We could get a million dollars. We could get it in cash.” Not long after that meeting, Dean went rogue and wound up as the star witness in the summer ’73 Watergate hearings.

Nixon’s self-destructive bunker mentality is unique in presidential annals, but Dean also believes that the cover-up instinct is rooted in human nature. Citing the work of University of Minnesota Law Prof. Richard Painter, he says that when lawyers and people in public life get caught in a bind (what Painter calls “a loss frame”), there is often “a cognitive bias toward concealment.” In other words, people double down rather than ‘fess up – even when the first option is irrational and leads to ruin.

Let that be Nixon’s legacy, a cautionary lesson for all future presidents. And Dean himself hints that his journey into the relevant past may be complete: “I told (wife) Mo that the men in my family start to lose their hearing in their ‘70s – which is where I am – and God forbid that the last voice I hear is Richard Nixon’s.”

——-

But enough about Nixon. Today, there’s a far more fun anniversary – at least for Beatles fans. On this date 45 years ago, they traversed the Abbey Road crosswalk for their final album cover. Twenty years ago today, on the 25th anniversary, I was living in London a few blocks from the crosswalk. So, in my capacity as a foreign correspondent for the Philadelphia Inquirer, I wrote about the fan festivities at the scene. The quote near the bottom, from Sandy Robbins, says it all.

Follow me on Twitter, @dickpolman1, and on Facebook.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.