An hourglass-shaped mountain? Princeton scientists find more room for threatened species

Listen

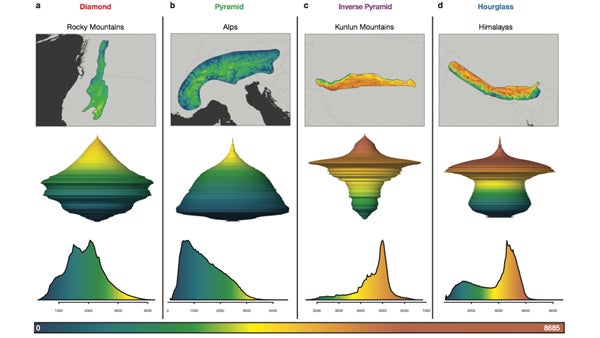

For all the range shapes except pyramid, land availability can be greater at higher elevations than it is farther down the mountainside. Those ranges, such as the Himalayas, shown here, are formed by a series of slopes that rise to open plateaus situated at the base of yet more slopes. (Photo by Paul Elsen/Princeton University Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology)

With global warming, scientists often speak of the ‘escalator’ effect: species moving up mountains to stay within tolerable temperatures. It’s been assumed species will suffer because they’d find diminishing space as they move upslope. But research from Princeton University finds that dogma is based on a misunderstanding of how mountains are actually shaped.

“Pyramids turn out to be the minority around the world,” says Morgan Tingley, an ecologist and co-author on a new Nature Climate Change study.

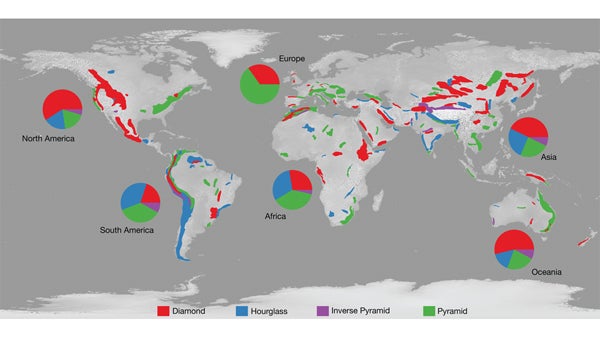

Together with Princeton graduate student Paul Elsen, Tingley used satellite data to classify 183 of the world’s mountain ranges. While the Appalachians and Alps conform to the stereotypical pyramid shape, about 70 percent of ranges actually have more land area in some middle and upper elevations.

(Image courtesy of Princeton University Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology)

(Image courtesy of Princeton University Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology)

The Himalayas, for example, have wide expanses near both the top and bottom, giving the range an hourglass-like profile. Indeed, it was during field hikes there in India that gave Elsen the idea to first investigate mountain shape.

The discovery suggests that select species, such as the Himalayan monal, a brightly colored peacock-like pheasant, might benefit as global temperatures rise.

“In the world of mountain research we’ve kind of always assumed that every species is a loser,” says Tingley, who is now a professor at the University of Connecticut. “With these different shapes of mountains, there are both winners and losers. It depends on who you are, where you are, and what shape of the mountain you live on is.”

Princeton researchers identified four primary shapes for mountain ranges. (Image courtesy of Princeton University Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology)

Extra space, both authors caution, doesn’t necessarily mean a species will fare better. For species already living at the highest elevations, the new research won’t help—there’s nowhere for them to go. But incorporating mountain shape into preservation plans can potentially improve those efforts.

“Now it enables conservation biologists and land managers to prioritize their conservation investments towards those bottleneck zones,” says Elsen.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.