Investigating 200-year-old plant remains found in a Bartram’s Garden attic

The well-preserved collection of seeds, nutshells and other plant plants offer a glimpse of the daily meals of Philly’s founding botanists.

Listen 2:35

Bartram's Garden in southwestern Philadelphia preserves the home and garden of the 18th century naturalist. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

A few years before the French Revolution, William Bartram shipped over to the French government 50 types of agricultural seeds he’d collected, along with documents showing their names and a short essay about how they were used.

One of the items listed was buckwheat. In the letter, Bartram wrote: “It’s a very useful and wholesome grain. The manner we use it is thin cakes made from fine flour on a hot iron plate.” He also noted it was served with coffee and tea, and was one of the most common meals among all ranks of people.

In the late 18th century, that was Bartram basically saying he liked to eat buckwheat pancakes.

Although he’s considered one of the founding fathers of North American botany, little has been known about what this namesake of Southwest Philadelphia’s Bartram’s Garden ate on a daily basis.

But now, a study at the Penn Museum, more than 30 years in the making, is teaching researchers what kind of fruits, vegetables, nuts and seeds the Bartram household grew for its own meals, outside the business of selling seeds to wealthy Europeans.

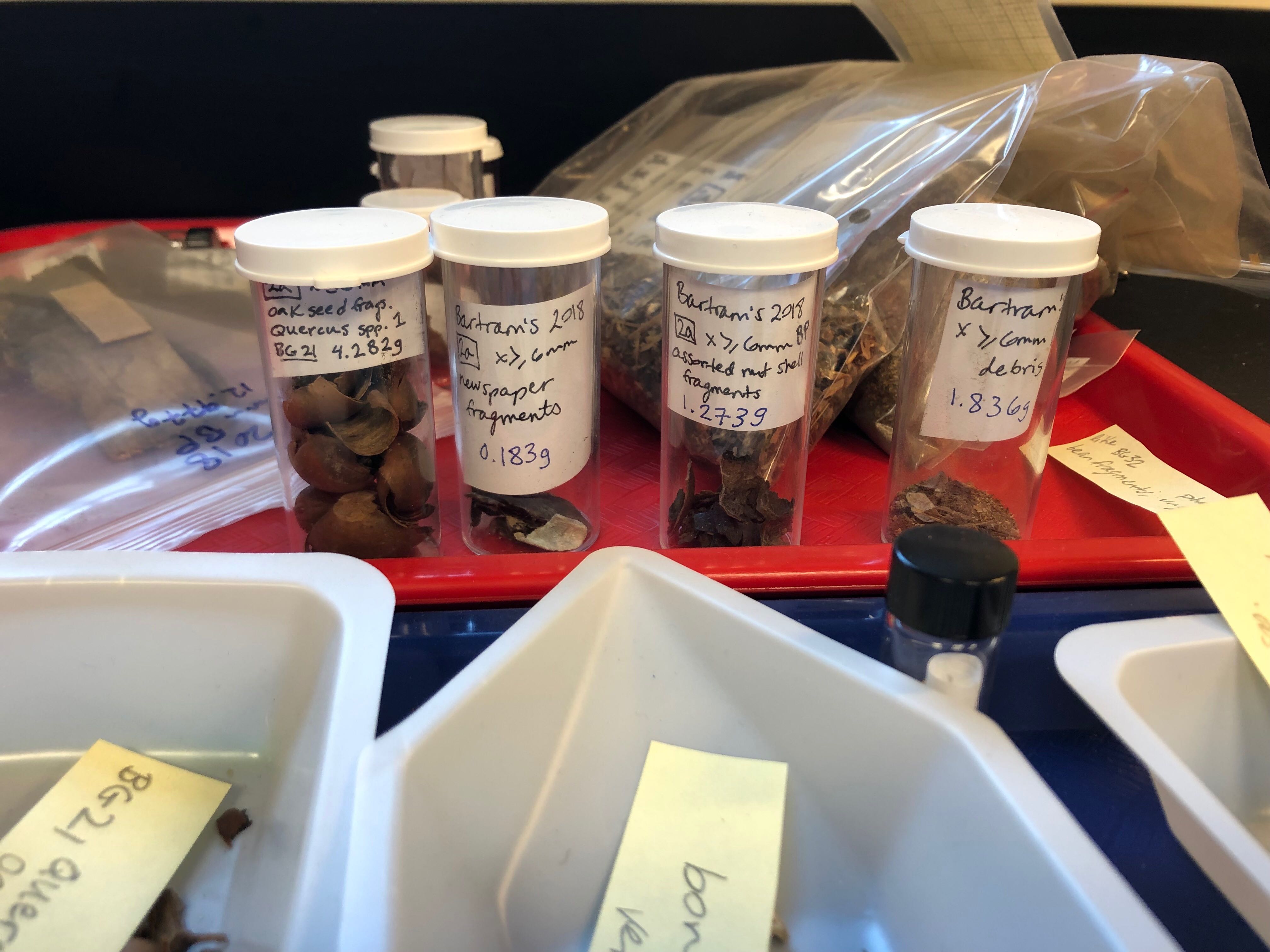

Led by Chantel White, an archaeobotany teaching specialist at the Penn Museum, the study involves bits of plants well preserved under a unique set of circumstances.

“This collection of seeds and nutshell and other plant parts survived, not because it was in the garden soil,” White said. “Basically, what we are looking at is a snapshot of what the rodents at the Bartram’s house and Bartram’s Garden were interested in storing in their nests and interested in eating.”

In the 1970s, architects working on restoration of the Bartram house discovered an assemblage of dry, dusty seed and plant remains under the attic floorboards. For reasons that are unclear, they decided to vacuum up the material and seal it in plastic bags.

Until last year, it sat untouched on the grounds of Bartram’s Garden. Joel Fry, the curator at Bartram’s, said there was no one who had the expertise to analyze it. But when White began bringing her students to visit the gardens a few years ago, he suggested that they take the material and begin analyzing it.

It’s probable that the material spans different generations of Bartram’s Garden, Fry said, but some of the oldest plant remains could certainly be from the 1810s to 1820s.

Among the more distinct items found in the collection so far are small cobs of corn grown by local Native American tribes along the Schuylkill. Peanut shells, the remains of kidney beans, parsnip seeds, and magnolia pods are also included in the finds.

Plus, they discovered a peach pit that — as attributed in the notes by William Bartram — supposedly grew spontaneously in Bartram’s Garden as people spit pits out onto the ground.

“He notes …’The fruit is moderately large and round, and of a pale yellow color, almost white, of a rose blush on the side next to the sun. Few peaches excel in taste and fragrantry,’ ” White said. “You’re getting a sense beyond just the peach pit, instead of what it looked like, and what it tasted like and what it smelled like. I think it’s those sorts of sensory experiences that give us a little more understanding of what life would’ve been like in the Bartram’s Garden.”

Part of the reason the material is so well preserved is because it was kept underneath the floorboards of the attic, a dry place, and out of the elements.

As an archaeobotanist, White said, much of the material she studies that has survived decades or centuries is often burnt and harder to identify.

“You can see the colors of the beans, of the many different specimens, you don’t have to deal with the effects of everything having been burned, that really alters sometimes the shape and the size of the specimen,” she said. “Here, we can make species-level identifications because they are preserved really as they were.”

Since their analysis began last year, White said, she and her students have probably only looked through less than 20 percent of the vacuumed material. She estimated they could spend years studying the plant remains.

A list of local agricultural sources has proved to be a “treasure trove” for White and her team.

“We are finding all of these plants from the kitchen garden, and they were not part of the seed business,” she said. “They were the things they were growing and eating as a family.”

Many of the seeds and other remains that were grown and collected by the Bartram family were known to researchers through the family’s written documents. But now, there’s an archaeological record to back that up.

Juliet Stein, a recent Penn graduate, has been studying smaller fractions of the material under a microscope for the past year. She said it’s fascinating to study the material in Philadelphia, especially amid a growing interest in urban gardening right here in the city.

“That’s exciting, especially for someone like myself who is heavily interested in researching where my food comes from and what’s in it and what’s not in it,” Stein said. “And even people nowadays who are interested in something as innocuous as gluten — or GMOs, or Big Agro — it’s not exactly what Bartram was doing 300 years ago, but it’s in the same vein in that we are having this renewed interest in food and sustainability, and there’s even a renewed interest in growing our own food.”

“We see a mirror of this 300 years ago, so it’s kind of interesting to get to live in both worlds,” she added.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.