In ‘Whitman, Alabama,’ the bard from Long Island goes down South

The series of short films bring Walt Whitman’s poetry to Alabama where regular folks recite lines from ‘Song of Myself.’

Listen 2:11

A film featuring the residents of Whitman, Alabama, reciting Walt Whitman's "Song of Myself" is the focal point of an exhibit at the Philadelphia Museum of Art celebrating the poet's 200th birthday. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

The Philadelphia Museum of Art has installed an ongoing documentary film project in its gallery, as part of the city’s yearlong celebration of the 200th birthday of Walt Whitman, the seminal poet who lived the last years of his life in Camden.

“Whitman, Alabama” is a series of short video vignettes, each ranging from 2 to 12 minutes, featuring of residents of Alabama reciting passages of Walt Whitman’s poem “Song of Myself.”

Whitman “dug deep to do something vast, to understand who we are as this crazy lot of people who are Americans,” said filmmaker Jennifer Crandall. “I thought it would be neat to take a poem written by a northerner and have it brought to life by the many voices of southerners.”

Fifty-two sections of the film are planned, to coincide with the 52 parts of the poem. Crandall is about half finished, showing 25 parts at the museum.

The project was birthed by the Alabama Media Group, which owns several newspapers and news websites in the state. In 2015, it launched an artist residency program; Crandall was the first artist to be accepted.

-

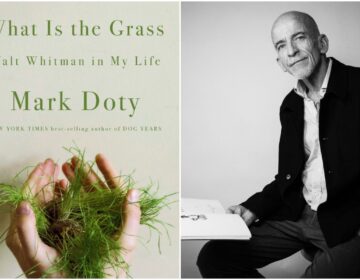

Filmmaker Jennifer Crandall, the creator of “Whitman, Alabama,” studies some of the photographs that were selected to accompany her installation at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

“It’s a region of the country not well understood outside the South,” she said. “Often it’s disparaged or misunderstood in the media.”

Crandall’s subjects are a varied group: a cattle rancher; a luthier; a farrier; a prisoner; and immigrants running a Vietnamese restaurant. A young West African woman wearing a hijab struggled to pick through verse 17; she feels more comfortable translating Whitman’s sometimes difficult language into her more familiar Fulani tongue.

Celebrating themselves

They were selected through a combination of word-of-mouth and serendipity.

“I was invited to a church, and I met Virginia Mae after seeing the play she was in,” said Crandall, talking about a 97-year-old community theater actress, Virginia Mae Schmitt, who opens the series by reading the first verse: “I celebrate myself, and sing myself…”

Schmitt died shortly after filming.

“For verse 43, we hit the road and saw someone changing his tire on the side of the road,” said Crandall. “We pulled over and met him.”

For verse 20 (“I find no sweeter fat than sticks to my own bones…”), the film crew went to Tuskegee University as its football team played a homecoming game, capturing the pageantry of marching bands and cheerleaders.

Watching the scene unfold from a seat in the stands of the Alumni Bowl, a young black cheerleader sits — as if inside a bubble surrounded by the excitement of the game — to recite lines written by a gay white man from Long Island more than 150 years ago:

I know I am solid and sound,

To me the converging objects of the universe perpetually flow,

All are written to me, and I must get what the writing means.

“We are all connected. We get to see Whitman’s poem come through them as they read it,” said Crandall. Whitman and the state of Alabama even share the birth year of 1819.

Meeting a moment

“But something happened that I didn’t quite understand,” Crandall said.

The project spins a bit of cinematic magic. Crandall cuts seamlessly between the action of the subjects’ lives and Whitman’s lines. Cheerleaders sweat. Felons fidget their fingers when standing in front of a judge. Parents running a busy Vietnamese restaurant are distracted. The poetry happens in the same space as regular life.

“These people are meeting a moment that doesn’t happen any other way,” said Crandall. “They are being asked to read poetry on camera. I don’t know how many times that happens in their lives – probably none. It’s a portrait of that moment. It’s a portrait of someone who has said yes to a strange ask.”

For its installation at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, “Whitman Alabama” is surrounded by a selection of photographs from the museum’s collection, including work by Zoe Strauss and Lucas Foglia. A suite of snapshots of African-Americans of unknown origin, likely mid-century, is also on display.

Assistant curator Amanda Bock felt the snapshots — donated from the Peter Cohen collection of vernacular photography — suited Crandall’s film project nicely.

“We don’t know who took them, we don’t know who’s pictured in them, and we don’t know when they were taken,” said Block. “They are very personal. There’s a story you can tell, but you don’t know if it’s the story being told by the photographer.”

“Whitman, Alabama” and the attendant photography exhibition will be on display until June 9.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.