In the Gap: African American doctors

-

“I'm feeling like I have a long way to go, but this is the first step toward everything. It's official. This goal is not only possible, but realistic.” -Bernard Nelson, First-year student, Class of 2015, Drexel University College of Medicine.

-

“Many young black children have never seen a black doctor, consequently, they don't have mentors to give them career guidance, and if nothing else a pat on the back.” -Oncologist Edith Mitchell, Thomas Jefferson University

-

“People like to understand that their doctor understands them, some of that is race, some of that is ethnicity. Some of that is personal background.” - Dr. Anthony Rodriguez, Associate Dean, Student Affairs and Diversity Drexel University College of Medicine.

-

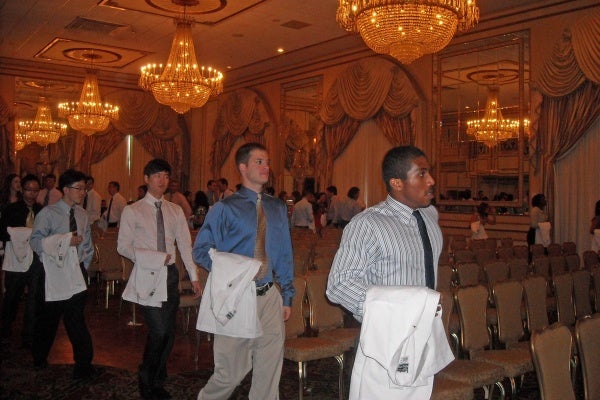

The class of 2015 line up--with white coats folded neatly--at the induction ceremony for Drexel University College of Medicine.

-

First-year students stand to take the Oath of Hippocrates during the White Coat Ceremony for the Drexel University College of Medicine.

About 6 percent of the nation’s physicians are African American; while about 13 percent of the population is black. Many experts say that gap hinders health care.

So, does race really matter in medicine?

The In the Gap: Voices from the Health Divide is a news and dialogue partnership between WHYY 90.9 FM and 900 AM WURD. Taunya English will discuss this story on WURD’s HealthQuest Live show on Tuesday, Aug. 30 at noon.

About six percent of the nation’s physicians are African American; while about 13 percent of the population is black. Many experts say that gap hinders health care.

So, does race really matter in medicine? Talk to Thomas Jefferson University oncologist Edith Mitchell and she shares a story from her days as a young fellow.

The patient had breast cancer, and Mitchell recommended an X-ray, then reached for her pad to order the test. The patient said she already had a prescription.

“It turns out she had been in that clinic every July for four consecutive years, and each time she took the slip and put it into her pocketbook and she still had it,” she said.

The woman’s church considered X-rays harmful to the body. So Mitchell worked with that belief and found an alternative treatment that slowed the woman’s cancer. Mitchell is convinced the patient finally felt heard because she’s an African American and the patient was too.

“It’s all a part of listening. Others had heard it from her before, and told her: ‘You absolutely have to have this X-ray, it’s what we do in cancer,'” she said.

Mitchell works on diversity efforts at the Kimmel Cancer Center. She says patients are more likely to follow doctor’s orders and stick with a care plan when they’re comfortable with their physician.

| Total Enrollment | Black | %Black | |

| University of Pittsburgh | 689 | 60 | 8.7% |

| University of Pennsylvania | 755 | 64 | 8.5% |

| Temple University | 769 | 60 | 7.8% |

| Drexel University | 1112 | 61 | 5.5% |

| Penn State University | 611 | 31 | 5.1% |

| Commonwealth | 130 | 3 | 2.3% |

| Thomas Jefferson University | 1094 | 21 | 1.9% |

| Total/Avg. | 5160 | 300 | 5.8% |

“People like to understand that their doctor understands them. Some of that is race, some of that is ethnicity. Some of that is personal background. I was raised by a single mother, I understand what it is when you’ve got a sick kid and you’re a single parent,” said Dr. Anthony Rodriguez, associate Dean of Student Affairs and Diversity at Drexel University College of Medicine.

For a long time, experts discounted the idea that black doctors might help black patients stay healthier, but Rodriguez says recent research suggests, sometimes, it’s true.

“They are gathering that type of data that people tend to do better with a physician of their culture or background. Their diabetes care tends to be better, their readmission rates tend to be better because people tend to understand some of those issues that then lead to the problems,” Rodriguez said.

Drexel is helping to boost the number of black physicians by growing its own candidates through the university’s Pathway to Medical School program.

“It’s a post-bac (post-baccalaureate) program. It’s for people who statistically, don’t necessarily look like they’d do well in medical school, and therefore aren’t getting in,” he said.

The program is for people underrepresented in medicine; poor students, rural students as well as ethnic and racial minorities.

“I see this program as one of the few ways we are going to increase diversity in medical schools, just because the applicant pool is not that great,” Rodriguez said.

The applicant pool is not so great, Rodriguez says, because too many of the school systems where black kids grow up don’t give them the science background they need to get into medical school. He says black students who do have the grades and test scores to qualify sometimes get discouraged by medical school costs.

“Say you’re a very smart African American, first generation in college. You’re going to often hear from your family: ‘Why do you want to waste four more years of your life and go so heavily in to debt to be a physician? You can go and get a really good job now,'” Rodriguez said.

Mentors also matter. When 25-year-old Bernard Nelson was growing up in Northern California, he says none of his doctors was black.

“None at all, never had one to this day. Not a pediatrician, nothing. When you don’t see too many that resemble you, you think that’s not in your options, you don’t think that’s one of your realistic expectations,” he said.

Nelson defied expectations this month, when he joined the class of 2015 at Drexel’s White Coat ceremony for first-year medical students. After reciting the Hippocratic Oath with his classmates, Nelson was all smiles.

“I’m feeling like I have a long way to go, but I’m glad this is the first step toward everything. It’s official. This goal is not only possible, but realistic,” he said.

Nelson went to the University of California, Berkeley but still struggled with medical school entrance exams and got wait-listed, so he joined Drexel’s post-bac program last year, where he and more than 50 percent of his classmates were black.

“I’m actually half Filipino and half black, I consider myself both,” Nelson said.

Students in the program sit-in on first year classes, re-take exams and connect with mentors. Succeed and you’re guaranteed a spot in the next medical school class.

“When I came to this program, I improved like crazy, so I was like ‘Oh, OK, well, I deserve to be here, now.’ It’s not like you kinda just got in,” Nelson said.

Nelson’s not even a doctor yet, but says he’s already had a patient get excited to see a young black man in a white coat.

“I don’t want it to mean that much, but then at that moment it did. I can’t wait for the day where that’s not going to be somebody’s source of pride. It should just be I’m an aspiring doctor, period. I happen to be African American.” Nelson said.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.