In the final days of Corbett, budget chief Zogby reflects on his quest for school reforms

Listen

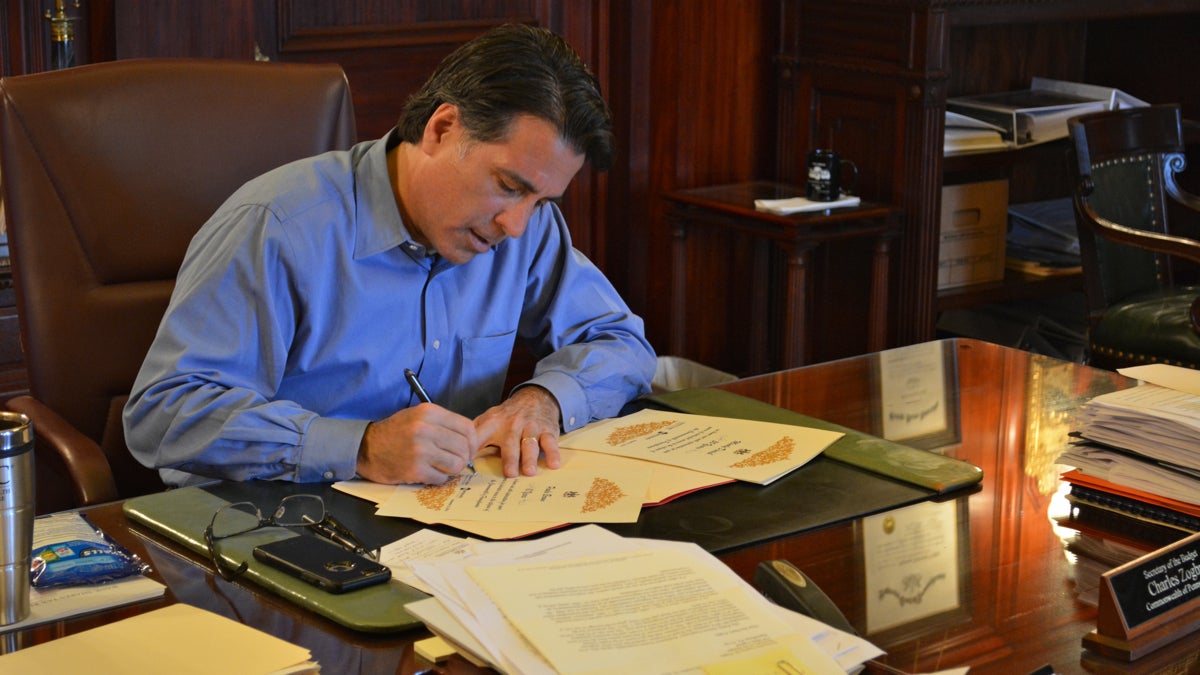

Pennsylvania Budget Secretary Charles Zogby (Kevin McCorry/WHYY)

As the Corbett administration draws near its final days, perhaps the departure of Pa. Budget Secretary Charles Zogby marks a radical shift in education philosophy.

It’s a cold December day in Harrisburg, where the streets and the echoing halls of the state Capitol lie dormant between legislative sessions.

In a handsome executive-wing office of mahogany and leather, a copy of the Wall Street Journal sprawled across his desk, state Budget Secretary Charles Zogby has already begun boxing up his belongings.

“Don’t make me out to be the villain,” he says, half joking, referring to his supposed image among traditional public school advocates.

As the Corbett administration draws near its final days, it’s Zogby’s departure that perhaps best marks the radical shift about to occur in executive-level education philosophy.

To his ideological opposites, Zogby’s a union buster, a privatizer, a profiteer. But the way Zogby sees it – through three governors and an eight-year foray in the private sector – it’s always been all about the children.

“Anything that I’ve done, it’s really been trying to help those most in need get a better shot at a better education,” he says.

In Pennsylvania, if you had to craft a short list of the players who best advanced the conservative public school agenda over the past two decades, Zogby’s name would be on it.

“Who else will be left that eats, sleeps and breathes school reform?” he asks.

The question hangs in the air as he considers the state lawmakers who’ve come and gone, but who shared his passion for choice and accountability.

Through Zogby’s window, work appears stalled on the Capitol’s roof as smoke curls from stacks in the distance. Inside, the grand office hums with the sound of an incessant heat compressor that Zogby cannot control. A box of decorative knick-knacks sits packed on his glossy wooden conference table. Still on display on a far shelf reads a framed quote: “Nothing stimulates the imagination like a budget cut.”

“When will I ever have a nicer office than this, right!” he exclaims wryly. “Kinda one of those things you just reflect on as an added positive to a job that maybe hasn’t had a lot of those.”

Good soldier

To some advocates, Zogby earned the villain’s mantle early in his tenure as Gov. Tom Corbett’s budget architect. Corbett’s first budget, in 2011 – timed with the expiration of federal stimulus funding – sent shock waves through the education community that are still being felt to this day.

Without the stimulus cash, classrooms took a tremendous hit, even though the Corbett administration forwarded a budget that increased the state’s basic education subsidy.

Zogby labeled the 2011 budget address “a day of reckoning.”

Effects on classrooms – especially poor, urban ones – were made worse as the Corbett administration slashed other line items that aided public education, such as the one which helped districts defray the added costs of charter schools.

All the while, as state pension, health-care and debt obligations grew, Corbett prioritized a business-friendly, anti-tax philosophy over restoring classroom resources – a gambit that likely sunk him in his quest for another four years of mahogany and green leather.

Contemplating these austerity budgets, Zogby, with jet-black hair greying at the temples, characterizes himself as a “good soldier” who found ways to get revenues in line with expenditures without tax increases as Corbett grappled with “the most difficult set of circumstances of any governor to take the office.”

“We did the best that we could. And I think people are going to see, as the new team will coming in, there are no easy answers,” he said. “The election may have changed the players, but it really hasn’t changed at all the challenges that are facing state government.”

Those challenges include a $2 billion anticipated budget shortfall for 2015 that Corbett’s critics attribute, in part, to the one-time cash infusions used to balance last year’s spreadsheets.

As we talked, Zogby, a native of Utica, N.Y., not far from Cooperstown, paced his office with a well-worn baseball, tossing it from hand to hand.

“Ah just, you know, just a baseball to hold,” he muttered. “I’m a baseball fan. I live for baseball.”

If baseball is first, education policy makes for a close second.

A dyed-in-the-wool Republican, Zogby volunteered for President Ronald Reagan’s successful reelection bid in 1984 and soon after found a philosophical home working for former Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Ridge – himself a major champion of school vouchers and charter schools.

Zogby has a distinct vision for public education, one that’s a sharp departure from tradition.

“When you dial it all back, what’s public education?” he asks. “It’s public dollars supporting school students with public accountability. It doesn’t necessarily mean that the public must own the means of production, if you will.”

“My sort of flip analogy is food stamps,” he says. “We give people food stamps; the government doesn’t run grocery stores.”

Zogby became policy director for Ridge in 1995 and then state Education Secretary in 2001 under his successor, Mark Schweiker.

Along the way, Zogby had a major hand in crafting some of the most impactful pieces of legislation the state’s educational landscape has seen: Pennsylvania’s charter and cyber charter laws; the empowerment zone legislation (now expired) that allowed the state to take over troubled school districts for poor academic performance, as well as the law that created Philadelphia’s state-held School Reform Commission.

In his office hang pictures of Ridge and him ceremonially inking these, his proudest accomplishments. Nowhere hangs a picture of him with Tom Corbett.

‘Battle’ of a lifetime

Throughout his years in Harrisburg, Philadelphia’s schools were the challenge that fascinated and frustrated Zogby most. He can’t see why some school advocates in the city hold on so tightly to what he views as failed models.

“In Philadelphia, we know for instance that there’s schools that are going to be open each and every year, right, that aren’t delivering for kids,” he said. “Yet, we send cohorts of kids into those buildings every year, and we know the result that’s going to come out at the end.”

When Zogby talks education, his rhetoric often careens into the militaristic. Teachers are in schools performing “hand to hand combat.” The quest to reform schools is “one of the toughest battles you’ll ever engage.”

And much to the chagrin of traditional education advocates – in the face of drastic cuts to classroom resources over the past four years – Zogby doesn’t believe additional funding is the weapon that’s going to win that war.

“I don’t think it’s a flotilla of cash that’s going to do it,” he said. “If you ask people whether we’re spending the right amount of money or not, they really don’t really know. If you told people that we’re spending $15,000 a year in most school districts to deliver education, I think the lot of them would say, ‘that’s a lot of money.'”

To him, real progress will only occur by weakening long-held union protections and holding teachers more accountable for student performance and growth.

“I think we have a lot of good people in public education,” he says, “but we have, in many places, a system in need of drastic reform.”

If Zogby regrets anything from his dozen-plus years in the capitol, it’s that lawmakers have failed to strip teacher seniority from the state school code and have been unable to mandate that teachers receive pay based on student growth and performance.

Critics point out that charter schools – which mostly enjoy the very staffing autonomy that Zogby would wish for districts across the state – have been around for 17 years, to largely mixed results.

Zogby blames the uneven results of the charter sector as a whole on poor oversight at the local level – calling for an independent, statewide authorizer and overseer.

“Having had a hand writing the original law, having helped write the cyber law, you’re never going to see me defend poor performing charter schools. I think we ought to shutter them,” he says. “If you’re not performing, you remediate. If you’re unable to remediate, you go out of business. Cause we’ll find another operator that can take your place.”

On this point he says charter proponents should be more vocal.

“One of the beefs that I’ve had with [The Pennsylvania Coalition of Public Charter Schools], frankly, is they jump to the defense of a charter school, right, no matter the performance of that school. Look at what the SRC did to close Walter Palmer. That was the right decision to make, and yet a lot of charter advocates, just because it says ‘charter,’ like we somehow can’t close that school.”

The Edison connection

In 2002, during his time as education secretary, Zogby successfully advocated for Edison Schools Inc., a New York-based for-profit education management company, to assume control of a slate of district-led schools.

Edison was awarded 20 of the 45 low performing schools that the district handed over to outside managers. Although those schools received more per-pupil funding, the private managers failed to exceed the gains made in district-run schools.

By 2011, under Superintendent Arlene Ackerman, the School Reform Commission got rid of its contracts with outside managers – a development critics of privatizations heralded as evidence of the failure of that model.

The K12 years

Between his government gigs with Schweiker and Corbett, Zogby was senior vice president of education and policy for K12 Inc., the nation’s largest for-profit operator of online public schools.

In January 2003, as Rendell was about to swear-in, Zogby left Harrisburg on a Friday and went to work for K12 Inc. the next Monday – a job he kept until January 2011, when Tom Corbett’s tea-party wave brought him back through the big green dome’s revolving door.

K12 Inc. has garnered widespread criticism – spurred in part by a lengthy 2011 article in the New York Times that took the company to task for low academic output, questionable enrollment practices and its ability to generate large profit margins on the backs of taxpayers.

“A portrait emerges of a company that tries to squeeze profits from public school dollars by raising enrollment, increasing teacher workload and lowering standards,” the New York Times wrote.

In Pennsylvania, K12 Inc. was a contractor for Agora Cyber Charter until 2014. Ex-employees there gave testimony supporting the criticisms in a lawsuit filed against K12 Inc. by its investors in 2012. School founder Dorothy June Brown faced fraud charges in a case in which a jury deadlocked on most counts.

Zogby, who helped K12 Inc. expand its reach into states nationwide, defended his work at the company.

“I never conducted myself in a way that was anything less than ethical, and I certainly didn’t support, or would never support anything that would be done at a corporate or a school level that would shortchange kids,” said Zogby.

“If there was somebody out there with the company or it was a company policy to somehow do enrollment churn or juice up enrollment figures or whatever, one, is that I never participated in it, but, two, if anybody did it and I was aware of it, there’s no way I would condone it,” he said.

As a counterpoint example, Zogby relayed an anecdote in which – while reading to children at a Christmas event at a BJ’s wholesale market – a young student and her mother thanked him for his efforts on behalf of cyber education.

“That speaks volumes about why I’m in this business,” said Zogby.

Appetite for more

Walking the halls of the nearly desolate executive-wing of the capitol, Zogby, a lover of the past, surveyed the trail of gubernatorial portraits that, starting with William Penn, winds into the Governor’s office.

With three of Zogby’s bosses soon to be counted in that row, the public’s first real glimpse at the abilities and priorities of the next person to occupy the office will come weeks after next Tuesday’s inauguration, when Gov-elect Tom Wolf delivers his proposed budget.

In that endeavour, especially when it comes to schools, Zogby says history is easy to predict.

“There’s just an insatiable appetite for more. Nobody has come through my door in the last four years and asked for less money,” he says. “They might have said, ‘don’t cut me,’ right, ‘don’t give me any more,’ but nobody’s asked for less.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.