In Philly, planners increasingly want to talk with you, not at you

Public planning meetings can be contentious, to say the least.

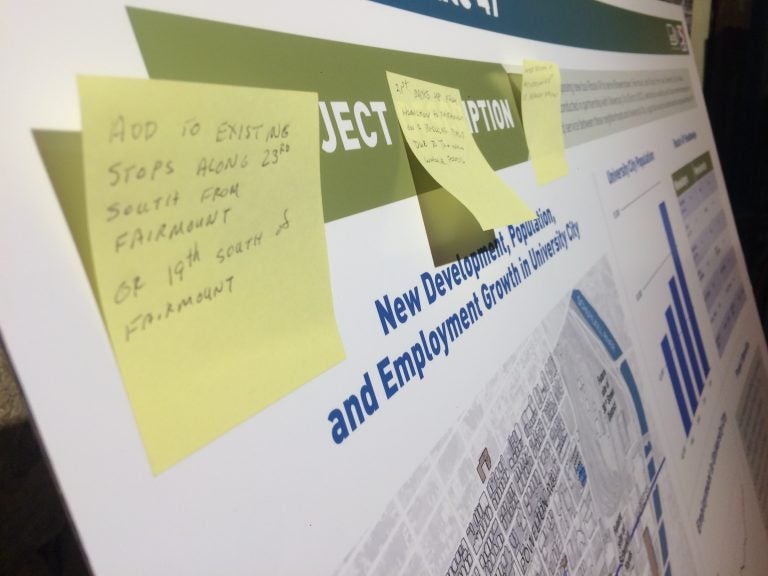

A poster board with residents' comments at SEPTA's Route 49 open house last year. (Jim Saksa/WHYY News)

This story originally appeared on PlanPhilly.

—

Public planning meetings can be contentious, to say the least.

Randy LoBasso would know. As the communications director for the Bicycle Coalition of Greater Philadelphia, he attends a lot of these sessions, which are used by city planners to inform the public about new proposals and solicit feedback. He recently attended one about the ongoing work to Lincoln Drive, the oft-flooded, winding roadway that runs along the Wissahickon Creek.

“It was an engineer-gets-up-in-front-of-a-crowd-and-explains-as-best-he-can-and-the-crowd-gets-up-and-yells-at-him sort of thing,” LoBasso said, lamenting “the heightened emotions of people at these meetings, where they get up in front, and scream, and get into these long-winded arguments with each other.”

If you’ve never had the pleasure of attending a public meeting yourself, NBC-TV’s Parks and Recreation did a pretty good job of capturing the anger, absurdity and attention deficit that can animate the typical town hall presentation: Government officials present some anodyne proposal — whether to protect a bike lane, for example, or upgrade an elementary school playground — and a parade of people march up to a microphone to scream obscenities at them, interspersed by another, competing parade of people screaming obscenities at the first parade.

Rather than sit through another rerun of this acrimonious production, urban planners in Philadelphia are increasingly trying to shape the meeting format to fit the subject matter in an effort to facilitate better, less-shouty deliberations among the assembled masses who attend such engagement sessions.

“Generally, when we’re doing a larger community event where we’re expecting large numbers, we’ll do an open-house format with poster boards,” said Kelly Yemen, director of complete streets at the city’s Office of Transportation and Infrastructure Systems (OTIS). “It does help [us] have more conversations with more people about the project. So, rather than one or two loud voices, we can talk to multiple people throughout the evening and really have time to dig into specific issues.”

If the medium is the message, open-house formats say, “Let’s chat.” They usually feature a series of poster boards set up across a large, open room, with a planner or two posted at each. The posters either provide information — the existing conditions, the context around the project, some of the proposals being set forth — or solicit feedback from those in attendance, often by asking them to write notes on Post-Its or pin representative dots on a map. The conversations tend to take place in small groups, if not one-on-one, allowing for the kind of respectful give-and-take expected among reasonable adults.

Contrast that with the more traditional town hall-style offering, in which one or two officials in front of a seated crowd go through a PowerPoint presentation, pleading at least once, and often in vain, for everyone to “please leave your questions and remarks to the end.”

After the presentation, arms shoot up in opposition, and one-by-one residents trudge up to a microphone to voice their displeasure. Getting up in front of a crowd to speak publicly is a phobia for some, but it sends a jolt of adrenaline coursing through the veins of many. That rush can trigger fight-or-flight instincts, and while it’s rare to see public speakers flee or resort to fisticuffs, they can be more combative in their tone and more prone to shout. At the same time, stress hormones impair higher-level reasoning, making it less likely that they will be able to fairly assess counterarguments against their own.

In the open-house format, residents’ concerns are easily voiced — all but the most timid of us can ask a question in a one-on-one setting. And misconceptions are gently corrected in semi-private — there’s no maddeningly embarrassing public call-out (which isn’t very likely to change opinions).

The open-house format “seems to have calmed some people, and it’s just a better way of getting information,” said LoBasso, who said he has noticed an uptick in the use of open-house discussions, and fewer town-hall lectures, in recent years.

Public meetings are widely regarded as necessary among modern urban planners, whose graduate programs raised them to lionize Jane Jacobs and lament Robert Moses. Moses was made semi-famous by Robert Caro’s Pulitzer Prize-winning “The Power Broker,” which explained in excruciating detail how Moses reshaped much of New York’s infrastructure with little regard for what insignificant others, like residents, might have actually wanted.

OTIS’s Yemen said the preference for open-house meetings was something she brought with her from her last job in Minnesota, adding that her Philadelphia department had deployed it at times before her arrival in 2016. Town hall, or lecture-style, meetings almost invite confrontation. “There’s just sometimes people who are looking to have a moment, to speak to the full room, and that can honestly drown out a lot of voices that we don’t hear from,” she said.

Since then, OTIS has had open-house meetings over a proposal to protect bike lanes on Lombard Street and a proposal to switch the bike lanes on Pine and Spruce to the left side of those streets. SEPTA and the Philadelphia City Planning Commission also used an open-house format to solicit feedback on proposed improvements to the Wissahickon Transportation Center and the nearby trailhead.

The City Planning Commission has long set meeting formats based on the gathering’s purpose, said executive director Eleanor Sharpe. “We’ve been doing this for a decade.”

If it wants to solicit feedback, the Planning Commission will use an open-house style or similar formats designed to encourage participants to speak up. If they want to simply inform a crowd and offer a chance for follow-up questions, then the town hall-style session is preferable. “That’s the difference: if we’re trying to push information or pull information,” said Sharpe.

That’s the approach the Delaware River Waterfront Corporation takes, said director of planning Karen Thompson. Lately, its sessions have been open houses. “We decide based on the project and based on the purpose of each meeting,” she said. “I think for particularly for these last few, they’ve just lent themselves really well to the open-house style.”

Sometimes, DRWC says no to both open houses and town halls, opting to go outside with its meetings. “For the Frankford Avenue Connector, we did a walking tour where we invited anyone in the neighborhood or anyone who used Frankford Avenue to come out and walk with us and the designers, to actually point out issues,” said Thompson. “We had a couple of key points we knew we wanted to stop at to get some feedback, but we also stopped a couple of other times when someone in the group wanted to ask a question or raise an issue. It was a great way of actually seeing the conditions on the ground and actually hearing from people who live in neighborhood.”

The planners also touted a more practical reason to favor open-house formats over town halls. “It allows people to come and go as it fits their schedule, so you don’t have to be there at a set time,” Yemen said.

“You can come and go as works with your schedule, and that lends itself to allowing a lot more people to potentially attend,” said Thompson. “We always want as many people as possible to come to our meetings and get as much input as we can.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.