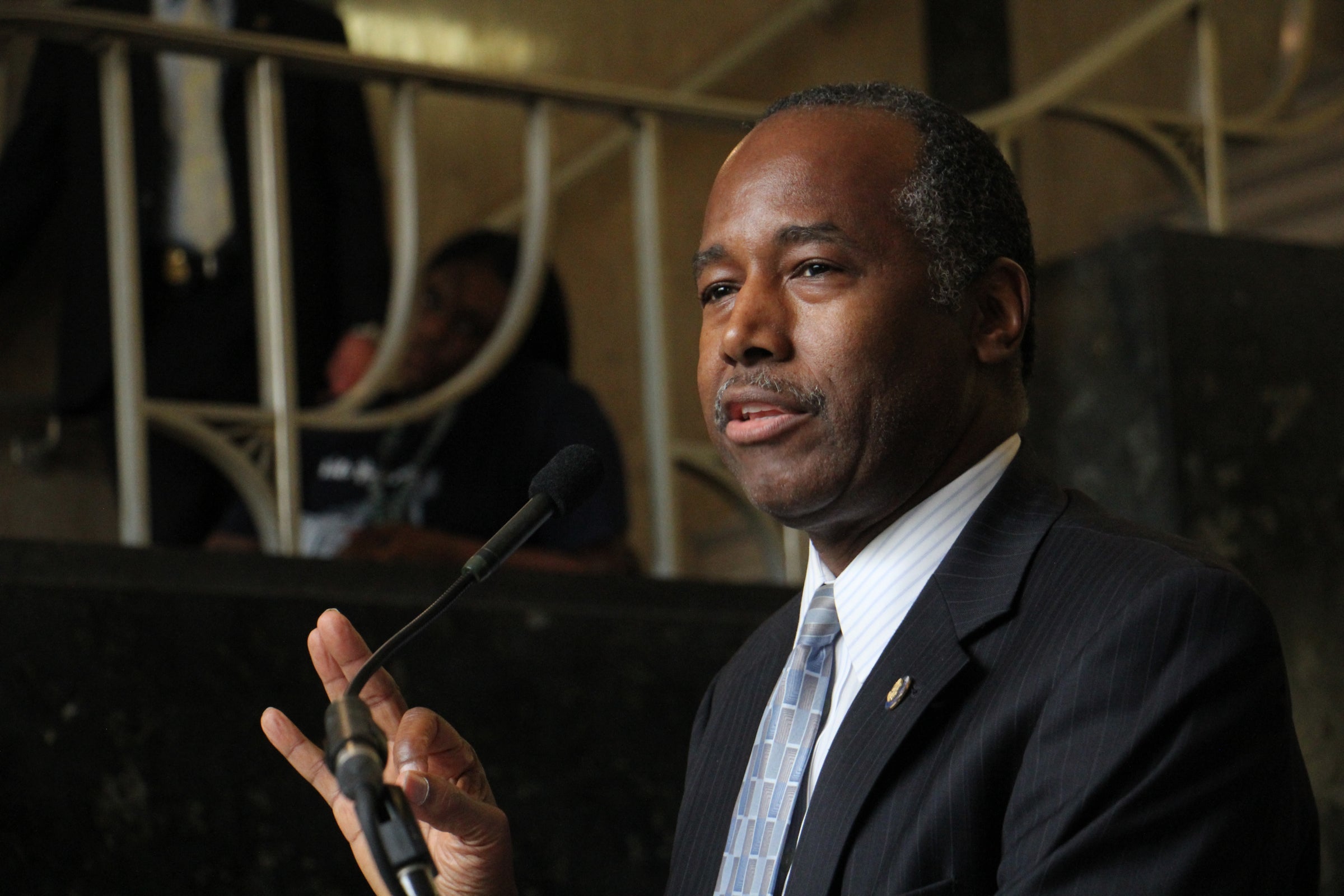

In Philly, HUD Secretary Ben Carson finds evidence that ‘housing-first’ policies work

Norma Cuevas remembers very distinctly when Pathways to Housing PA gave her the keys to her new apartment after two years of homelessness and a stint in jail.

“I said, I’m getting out of there where am I going to go now? What a feeling when they showed me that key,” Cuevas said on Wednesday at a roundtable held at the housing nonprofit’s North Philadelphia headquarters.

Cuevas, stable and in treatment after struggling with opiod addiction, was there to demonstrate the power of the “Housing First” approach used by the organization to address the needs of homeless people by giving them an apartment first. Unlike many service providers, those that follow a housing-first model do not mandate that people have a job, be in treatment, or achieve sobriety before they get a place to call their own.

Cuevas’s target audience: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Secretary Ben Carson.

HUD began promoting “Housing First” policies under former President George W. Bush. The concept gained momentum under President Barack Obama, but unlike many of the previous administration’s initiatives at HUD, this one has earned the favor of the Trump administration too. Under Carson, the agency has tweaked regulations to incentivize local housing organizations to adopt the model. During a visit to Philadelphia last year, the HUD secretary praised the policies extensively in an interview with PlanPhilly.

“The housing first initiative indicates an understanding that it actually costs more to leave someone on the street than it is to get them off the street,” Carson said in the interview last year. “[Then you] diagnosis why they are in that position, that’s housing second, and housing third is you fix it. A lot of people who find themselves in difficult situations actually have a great deal of potential and can become self-sufficient.”

But Carson didn’t get into policy during his Wednesday appearance. Instead, he listened to Cuevas, and the other participants, offering smiles and an occasional comment: “If we as a society stop fighting each other and we can use this stuff appropriately, we can solve a lot of these problems quite effectively.”

At another point in the conversation, he seemed to acknowledge the value of the social safety net that Trump’s budget proposals have sought to dismantle.

“I think we are starting to learn that it actually costs less to society to take care of people than to not take care of them,” Carson said. “Not to mention that people are resources and we have an obligation to take care of them.”

The embattled HUD secretary has faced a rough beginning to 2018, faced with unflattering profiles of his time on the job, a recent New York Times investigation into the agency’s retreat from fair housing enforcement, and a series of controversies over a $31,500 furniture set that broke internal HUD regulations on spending.

Unlike his last visit, Carson did not speak in front of a public audience, or answer questions from reporters.

“Unfortunately, the schedule didn’t allow time for questions from the media,” wrote Raffi Williams, Communications Director for HUD, in an email to PlanPhilly.

Instead, much of the limelight was given over to Pathways to Housing Pa, the city’s most prominent adherent to housing-first policies and a HUD grantee.

The organization was founded in 2008 as part of a radical new approach to housing the chronically homeless and those who suffered from severe mental health issues. City officials gave them a list of 125 people, most of whom suffered from persistent mental illnesses and substance abuse issues. Using local and federal grant dollars, the nonprofit found homes in Philadelphia for all 125 over the next two years.

Now the organization has five teams that support 365 people facing distinct issues, with the most recent addition being a group that helps those who struggle with opioid addiction. Another team focused on opioids will probably be added soon. Those involved in the program get to choose where in the city they want to live in and are then taken around to look at potential apartments. After clients get settled in, Pathways connects them to the services needed to address their particular struggles.

“It’s a good model for the city because we can get up and moving really quickly,” said Christine Simiriglia, CEO of Pathways to Housing. “We don’t have to build anything, we don’t have to deal with zoning, we don’t have to deal with NIMBY issues. The reality is we are a very poor city… with a lot of empty low-rent units. It’s better for the city if we fill them.”

Most of the organization’s funding comes from Medicaid, but the majority of dollars for housing come from HUD. City agencies and various philanthropies provide funds to fill in gaps that the federal agency does not cover.

Simiriglia said on Wednesday that the programs her organization depends on haven’t been affected by recent cuts to affordable housing programs in the same way that public housing programs have. (The most recent omnibus spending bill provided some new money for these beleaguered programs.)

At the end of the 28-minute roundtable, Carson thanked the participants and immediately left the room.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.