In Pa., less than 5% of teachers are people of color. The lack of diversity is hurting kids and schools

“Not only do we believe black teachers are important for black students, they are good for every student."

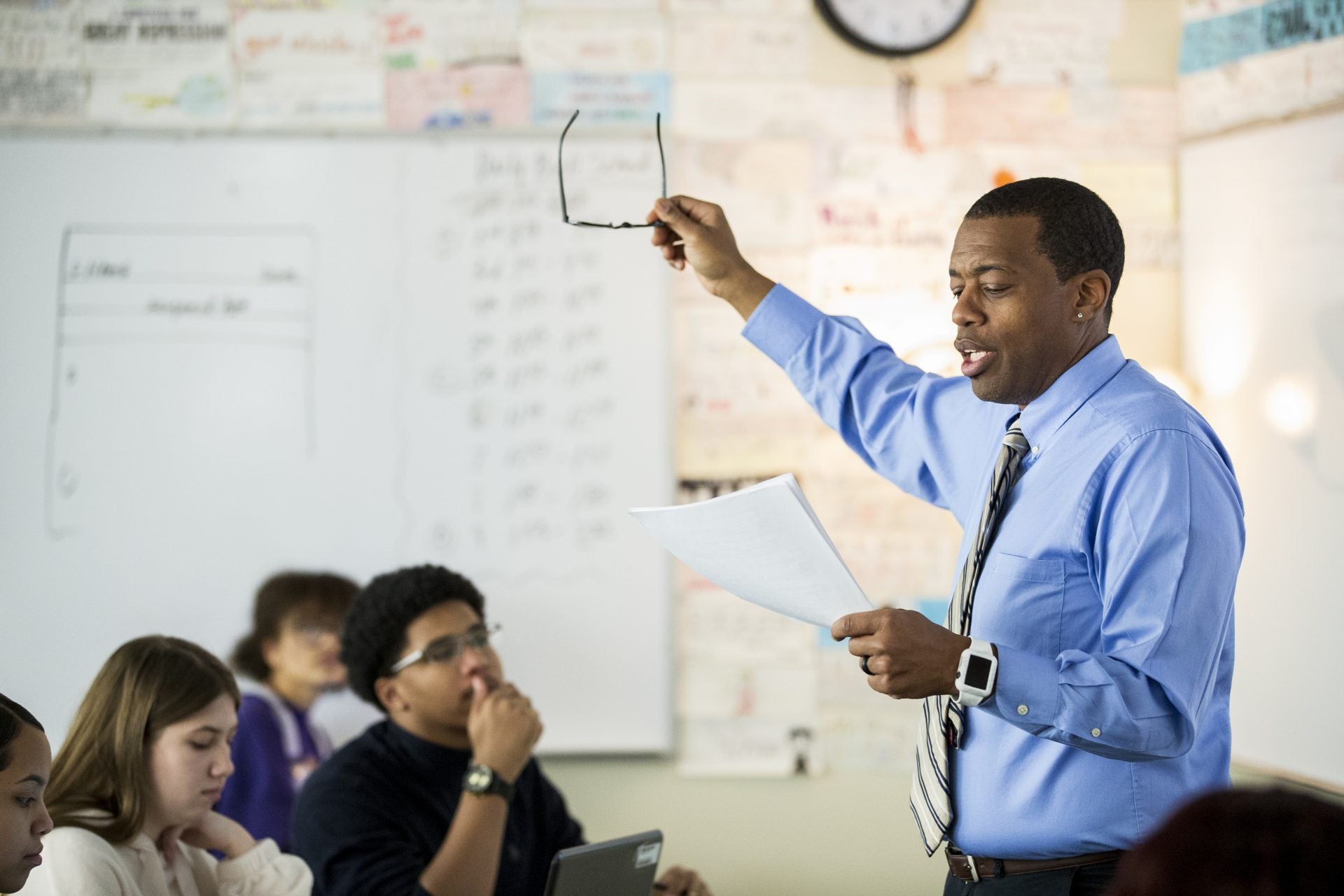

Head football coach and History teacher Joseph Headen is one of only a handful of teachers of color at Susquehanna Twp. There is a persistently low shortage of teachers of colors across Pa. 96 % of all teachers are white; the 4% of color are concentrated in Philly and Pitts. schools. The lack of teachers of color has a profound impact on the educational and professional experience of teachers and students. Jan. 16, 2020. (Sean Simmers/PennLive)

This PennLive article appeared on PA Post.

–

For a dress-down Friday shortly after the 2014 police shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., Amy Alexander, then a high school teacher, decided to wear a T-shirt emblazoned #mikebrown.

Some of her colleagues at the Penn Hills High School just outside Pittsburgh objected to her attire and complained to the administration. Alexander, who is black, was questioned by the school principal. Her colleagues, all of whom were white, were concerned that her T-shirt would incite a riot in the predominantly African-American school, she said.

Alexander said her T-shirt sparked vital conversations. Student after student, all of them black, shared their concerns about racial profiling and excessive police force. They told her they were worried that what happened to Brown, an 18-year-old African-American killed by a white cop, could happen to them, too.

“It gave me a chance to talk and discuss distal and proximal trauma with my students. To say it’s normal to be affected by something like this, even by things not happening in your community,” said Alexander, now counselor to the 400-student senior class at Penn Hills.

To some the episode may have seemed a provocative gesture, but for Alexander the T-shirt spurred an important teaching moment, allowing her and her students to discuss relevant and important race issues.

The reaction from her colleagues underscored the chasm created by the racial disparities in Pennsylvania public schools, where the overwhelming majority of teachers are white.

Pennsylvania’s teacher roster is the least diverse in the nation, as Pennsylvania Secretary of Education Pedro Rivera has said. Less than 5 percent of Pennsylvania’s teachers are people of color, according to the state Department of Education.

The gap between the state’s students of color (33 percent) and teachers of color remains among the most disparate in the country, according to Research for Action. The group analyzed data from the Department of Education and found that 55 percent of Pennsylvania’s public schools and 38 percent of all school districts employed only white teachers in 2016-17.

That number is a function of the historical context of teaching: Teachers have historically been white and female, in large part due to the college enrollment process. In fact, it’s a nationwide challenge.

“Pennsylvania is no different than any other state in the nation,” said Noe Ortega, the Deputy Secretary for Higher Education. “The challenge we have now is we know a little more about the benefits of having teachers of color in the classroom, especially where you have large populations of color.”

The disparity is particularly stark among male educators: 73 percent of all teachers in the state are women; men of color comprise slightly more than 1 percent of teachers.

The impact on students – and teachers – is profound.

The glaring racial disparity has negatively impacted student achievement, graduation and truancy rates, and the career or collegiate aspirations of thousands of children of color.

“It’s really outstanding how bad it is,” said Sharif El-Mekki, founder and director of The Center for Black Educator Development in Philadelphia, and a former Philadelphia teacher who spent 16 years as a school principal.

“People make assumptions. You think that a city like Philadelphia, which is so diverse, you would think the numbers are not as bad or that they mirror other cities across the country. You figure.”

A single black teacher can make or break the educational track of a black student, particularly one from a low-income household. Black students who have at least one black teacher in elementary school are more likely to graduate high school and consider college, according to a study out of the Johns Hopkins University. The results are even greater for black boys from very low-income homes.

But that’s not all. The disparity reinforces racist stereotypes and even negatively impacts the professional experience of teachers of color.

In fact, Pennsylvania teacher diversity mirrors that of midwestern states like Minnesota, whose schools are growing increasingly diverse, but its teacher workforce remains overwhelmingly white.

In a school district like Philadelphia, whose student makeup is almost 70 percent black, black male teachers account for about 1.9 percent of teachers.

“You start seeing how this plays out,” El-Mekki said. “Not only do we believe black teachers are important for black students, they are good for every student. It’s good for white students who are conditioned to not be in spaces with black people and especially nurturing black people in positions of authority. ”

At the core of the challenge is the student-teacher connection.

Alexander, who has a doctorate in education, said children of color, in particular, need figures of authority they believe can relate to them.

“This is important to them,” she said. “They are getting ready to go out in the world and find out where they fit and find their purpose. Race is not that determining piece either. There are African Americans who aren’t necessarily helpful in that respect, but race is helpful when it comes to someone’s sensitivity and cultural background.”

A changing landscape

Across Pennsylvania, student demographics continue to increasingly diversify with a growing number of districts becoming less white, and more brown and black. Yet, according to state education data, more than half of all schools and nearly 40 percent of the state’s 501 school districts employ only white teachers.

An inordinate number of students across the state navigate their entire school days – from riding the school bus, to a day of classes and evening sports practice – without seeing a person of color, certainly not a teacher.

“I am for some kids the first black male teacher they have ever had,” said Frank Howard Anderson, a fifth-grade teacher at South Park Middle School in the South Park School District in Allegheny County.

A 22-year teacher, Anderson is the only teacher of color in the district.

“From Kindergarten to the day they graduate, they will have no other minority teacher other than myself,” he said.

The fallout impacts not just students; teachers feel it as well.

Joseph Headen, a U.S. History, sociology, AP history teacher and head football coach at Susquehanna Township High School in Dauphin County, said he can attend a teacher conference and see few educators of color.

“Then you start to think about how many teachers of color you had, and, for me, I had one,” he said. “There is a huge disparity in the amount of teachers of color.”

Teacher diversity during Headen’s high school career may have been skewed given that he attended Bishop McDevitt High School, a private Catholic school, but his collegiate experience and teacher career have been far from unique.

During his collegiate and graduate studies at Bloomsburg and Shippensburg Universities, respectively, Headen was often the only person of color, certainly the only male of color, in the education track.

Throughout his early teaching posts, including student-teaching at Susquenita High School in Perry County, he was the only educator of color. At times he has been the only teacher of color in a district.

His current school, Susquehanna, ranks among the Top 10 most diverse schools in Pennsylvania – with a virtual 50/50 percent ratio of white students and students of color.

“It’s as balanced as you get in the student diversity aspect in a high school,” Headen said. “We do have staff members of color..I think there are two of us, if I’m correct. Most of our assistant principals, support staff, coaches, our head baseball coach, head basketball coach, football coach even swim, are of color, but in our building, teaching wise, our number resembles the statewide numbers.”

School districts across the state continue to increasingly diversity racially and ethnically. The Washington Post this year published a report looking at the changing makeup of the nation’s school districts. The report, measured diversity and integration using student race data from two years: 1995 and 2017.

According to the Post’s report, for instance, between those two years:

- The West Shore School District went from being 95 percent white to 82 percent white

- Cumberland Valley School District went from 95 percent white to 75 percent

- Central Dauphin School District went from 85 percent white to 51 percent

- Chambersburg Area School District went from 91 to 65 percent white

- Conestoga Valley School District went from being 90 percent white to 66 percent

- Manheim Township School District went from being 91 percent white to 67 percent

- Carlisle Area School District went from being 91 percent white to 72 percent

- Hazleton Area School District went from being 97 percent white to 44 percent

Amid the changes, the teacher ranks of the district remained constant – predominantly white.

The importance of diversity

Black educators say the importance of having teachers of color in classrooms cannot be overstated: The stark disparities have created a dearth of role models for young people of color and an environment that often lacks in the cultural sensitivities young people need to navigate difficult and impactful conversations.

“Some of the situations students go through would be difficult for people who are three and four times their age to be able to navigate and be successful,” said Robin Harris, a counselor and one of the few black educators at Thomas Holtzman Elementary School in Susquehanna Township School District.

“You are in a situation where you have to navigate these hard situations. Devastating situations,” Harris said. “Situations that are going to have an impact for the rest of your life and you are here and the majority of people who are here to assist you aren’t people who look like you or come from your community. I think people want to understand not just that kids come in and bring whatever they are going through, we bring in our own personal issues.”

While Holtzman Elementary has a robust student diversity demographic, with an influx of students from neighboring Harrisburg School District, the school’s teacher roster mirrors the overall state picture: the majority of the teachers are female and white.

Harris said the school’s teaching staff is dedicated, caring and conscientious, but she said not everyone is equipped to navigate some of the profoundly sensitive situations and home lives that students can bring to school.

“If you are a caucasian female coming from a situation that is not as diverse as Susquehnna and you are dealing with children who have situations that are unique, it may not be something you can relate to,” Harris said.

The gulf created by that disparity also leaves a void of cultural and racial sensitivities important to students and educators, regardless of race.

Black educators say they routinely negotiate situations in which black students are having to defend their attire, hair styles, even the mundane factors that create identity.

“Even something as everyday as quotidian as a name,” Alexander said. “I’m talking about educated adults who are supposed to be mentors asking, ‘What kind of name is that? Where did this name come from,’ and other cultural things that we should not be articulating.”

The impact: Beyond the immediate and personal

Thousands of black children and young adults in Pennsylvania go about their school days shut out from the difficult and impactful conversations about racial issues in the country simply because of the gulf of understanding in classrooms. Other times, they face persistent racial stereotypes, even racially hostile environments.

S-qy Featherstone, who is black and a senior at Penn Hills High School, said the lack of teachers of color contributes to that. He said racial undertones are a constant backdrop at his school, which has a student demographic of roughly 75 percent African American.

Penn Hills has two educators of color.

“It happens all the time. I try to ignore it,” said Featherstone, a member of the Black Student Union and a defensive end on the football team. “You can’t change how others feel towards you. You can’t change it at all.”

His school district has for months wrestled with issues of racial hostilities involving accusations that the Connellsville High School boys soccer team and fans used racial slurs against Penn Hills players during a soccer game.

Connellsville is a predominantly white school.

For students like Featherstone, the racial divide in school can be as subtle as it can be stark. He notes the fact that the heritage and history of his racial lineage is taught only once a year, during Black History Month in February.

“We are not at school just in February,” he said. “During Black History month last year we read a book and watched a cartoon about Martin Luther King. I had already seen it.”

The nuances sometimes turn stark.

Last year, Featherstone walked into one of his classes to find a substitute teacher. Featherstone was wearing a hoodie and had his ear buds in his ears.

“As I sat down everyone was looking at me,” said Featherstone, who next fall will attend Clarion University, where he will play football and study business sports management in the hopes of someday becoming a coach.

“The substitute was like, ‘Is that what you do everyday?…You need to be more safe.’”

“I’m like, what does that mean? Just because I have my headphones and a hoodie on? I walked in quiet, not disturbing anyone?’ It was plain sight racism,” Featherstone said.

The black educators who spoke to PennLive for this story said that the overwhelmingly white teacher roster in Pennsylvania reinforces negative attitudes towards African Americans and waters down the academic curriculum.

“Black kids in schools get a negative portrayal of black people,” El-Mekki said. “They don’t see themselves in the literature or history lessons. They go to a museum and it’s all white history. This is the whole ecosystem that occurs and its conscious and unconscious. That is dangerous. It reinforces, particularly for black children, poor identity and self worth, and for white children, it breeds white supremacy. If you grow up falsely seeing that no one else contributed now or then, it sets your world view.”

The dearth of teachers of color in classrooms also denies young black people the opportunity to see – and emulate – role models in positions of authority and achievement, said El-Mekki, whose Center for Black Educator Development is focused on growing the number of teachers of color in Pennsylvania, largely through peer mentoring and partnership between students in high school and college and teachers of color.

“We can recruit 1,000 folks but if the conditions are not right, and we are sending them back into a toxic environment. That’s not helpful,” he said. “Being black in America is very similar to being black in school. Racism does not dissipate. Schools are a microcosm of society. It’s the same experience. It behooves us to recognize that for us, folks of color, we don’t see color and race in a historical context.”

That day with the encounter with the substitute, Featherstone said that as with so many other days during his school career, he moved on quickly.

“I shrugged it off,” he said. “There are way more people like that out in the world. If I’m going to feel some type of way about one person for saying one thing, I wonder how my life is going to be when so many people are so much more ignorant.”

Featherstone believes that if his school district had more black teachers, he would have had a different educational experience. Under the current demographic breakdown of teachers to students – a predominantly African-American school in which every single student is enrolled in the free lunch program – the gulf of understanding between students and teachers at times seem insurmountable.

“Sometimes it’s not so easy to speak and let your situation be heard or known to someone that you continually think they don’t care or they show no emotion or empathy toward what you have to say,” Featherstone said. “I would rather speak to someone who can relate to how I‘ve been feeling and going through rather than someone who sits like a sponge and soaks it up and uses it for other purposes.”

Slow and little change

Featherstone’s experience is not unique to that of other students of color – past and present.

When she attended Central Dauphin School District during the 1970s and 1980s, Jill Gouse, who is biracial, had only one black teacher.

She attended and graduated from Central Dauphin East, one of the most racially and ethnically diverse schools in the state – then and now.

“I used to think what a shame,” said Gouse, who nine years ago returned to her school district as a third-grade teacher at Silver Spring Elementary. “It’s a shame that there weren’t more black teachers. That was the ‘70s and ‘80s but, I we are in the same boat.

Her two daughters, who recently graduated from Cumberland Valley High School, had no black teachers.

“It’s really important for students to see role models, people of authority that represent what the world looks like, what our communities look like, what our country looks like,” Gouse said.

“It makes it normal. For most of these students I have in class, I‘m part of the school and not the black teacher at school. Not the biracial teacher. I‘m just a teacher. I think it normalizes seeing that.”

The Cumberland Valley School District, her daughters’ school district, is in fact counted among school districts in Pennsylvania wrestling with a fast-changing student demographic makeup.

Until recently, the district, considered one of the top districts in the state, was predominantly white, but in recent years has increasingly become more diverse. In the process, the district is encountering the hurdles that are sometimes associated with racial disparities among teachers and students.

The district recently came under scrutiny amid allegations from students and parents of color that officials are not adequately addressing what they say is a climate of racial intolerance and racism in the district. Students and parents have multiple times addressed the school board to report incidents of racial and ethnic harassment, intimidation and bullying.

For district superintendent David Christopher, a former assistant superintendent at North Allegheny School District, where he was the only non-white employee, the matter is a priority.

“We would be remiss to discount serious concerns of racial tolerance,” he said. “As a district we have to promote what is in the best economic interest for students and teachers to work in diverse workplaces, to be culturally sensitive. It’s better for kids in the long run and better for all students.”

Christopher, who is of Indian descent and was recently appointed superintendent, has pushed for special initiatives and programs to tackle the challenges before the district. The district has involved the U.S. Department of Justice, the Anti-Defamation League, among some of its partners.

“Our challenge here is capacity,” said Christopher, whose district is literally bursting at its seems to find classroom space for the fast growing number of students. The school district employs 650 faculty members.

Central to Cumberland Valley’s effort to address intolerance is the fact that of the district’s 1,200 employees – professional and support – roughly 15 are persons of color, making the entire staff about 97 percent caucasian.

“It definitely needs to be higher,” said Michelle Zettlemoyer, Cumberland Valley’s director of human resources:

“For us it’s a vicious cycle if we can attract more people of color that would contribute to a more inclusive environment for staff and students and that’s good overall. It’s just a matter of how do you find them when the pool is diminishing overall in education ..as far as teacher candidates.”

Race impacts teaching and teachers

Teachers of color across Pennsylvania schools say they often feel obligated to defend black students amid a landscape of bias.

“I stick up for the black kids,” said Anderson, the South Park fifth-grade teacher. “It is very obvious sometimes the punishment that comes down for black students versus that for white students.”

South Park’s fifth grade is populated with 124 students: about five are African American; about the same number are of Middle East or Pakistani descent.

Anderson said that at times the biased treatment towards black students is stark.

“I‘m always being proactive in saying we have to make sure everyone gets treated fairly,” he said. “I‘m getting worn down because I try to take care of all the black kids. I have my own family, I coach football at a different school. I don’t want to use the term burden, but I get worn out sometimes. I have a lot more pressure than any white teacher that I teach with.”

In predominantly white districts, black teachers say negotiating racial intolerance can be difficult across the board – whether in dealing with other teachers, administrators, students and parents.

Diversity, they said, helps.

“The whole process of education in and of itself is learning who you are and finding out what you value, what you respect,” Harris said. “One of the big pieces of that is respect.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.