In Cobbs Creek, a home for the dead gets new life

A cemetery with a long, remarkable past – which, unfortunately, included periods of neglect and deterioration – is working on a new plan for a long, sustainable future.

Mount Moriah Cemetery, which sits along Cobbs Creek and borders neighborhoods from Southwest Philly to suburban Yeadon, has been maintained over the past seven years by a friends’ group aided by students, neighbors, fraternal organizations, and descendants of those buried on the grounds. This corps of volunteers has made slow but significant progress in reclaiming the gravestones from overgrowth, vandalism, and dumping, and in keeping the cemetery’s historic structures from crumbling.

Now the Friends of Mount Moriah Cemetery and their allies are working with the multi-disciplinary consulting group Fairmount Ventures on a master plan to be completed by this summer that will address the vast landscape, historic assets, community needs, and business options of the cemetery.

The goal is to create a plan that will ensure that the cemetery doesn’t again fall into neglect and decay. Volunteers can’t do it alone, says Paulette Rhone, board president of the Friends group. “We need to commit something in writing as to where we’re going and what it will take to get there.”

Reclaiming history

While 19th-century burial grounds like Laurel Hill and The Woodlands were created to accommodate the more affluent families of Philadelphia, the city’s African-American and Jewish congregations, benevolent associations, and other working-class groups set up their own cemeteries, places like Mount Moriah.

The sprawling burial ground was established in 1855 on 54 acres in the then-rural southwestern section of the city. The cemetery expanded to 380 acres over the next 100 years, making it one of Pennsylvania’s largest burial grounds. Veterans of every American war from the Revolution to the Korean Conflict are among its 80,000 graves.

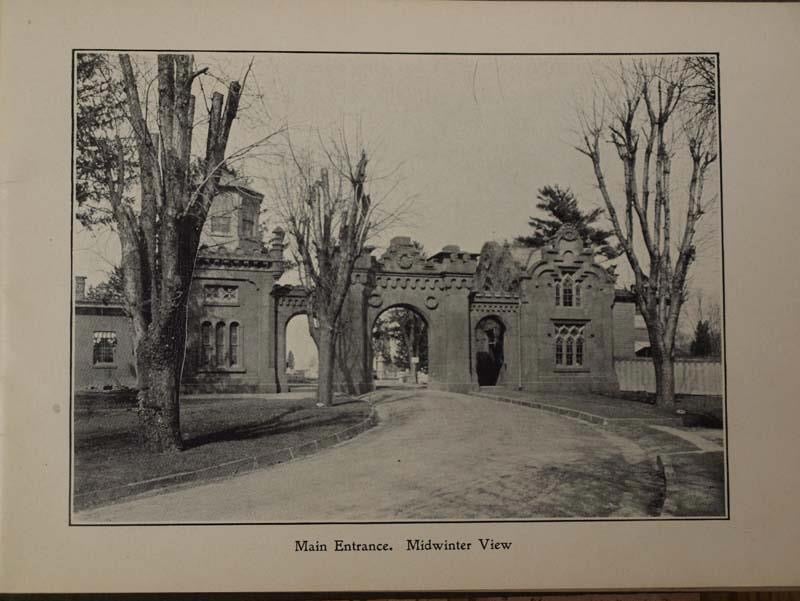

The majestic gatehouse near 62nd and Kingsessing streets was designed by Stephen Decatur Button, a prominent architect who created elegant entrances for cemeteries in Gettysburg and southern New Jersey, and designed the Gaul-Forrest Mansion (now Freedom Theatre) on North Broad Street and the stately Congress Hall hotel in Cape May. The Mount Moriah entrance structure is listed on the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places and last year was deemed eligible for designation on the National Register.

But the cemetery suffered from neglect by the former owners in recent decades, as knotweed and other invasive plants, untended trees, and illegal dumping covered the markers and decorative elements of the grounds. Fires damaged parts of the historic gatehouse in the 1970s, and other sections have deteriorated and collapsed over decades. The structure’s brownstone veneer has cracked, and it loses more pieces with each season of severe weather.

The Friends and other organizations have made steady progress in reclaiming the burial grounds and limited progress in preserving the gatehouse. They have enlisted the help of Boy Scout troops from the surrounding neighborhoods to clear overgrowth and debris; students from Penn, Temple, and Drexel to assist in preservation planning and civic engagement; and private contractors to reset headstones. The Friends’ Facebook page has over 5,000 followers, and a crowd-funding campaign to support work on the gatehouse raised nearly $35,000 last year.

“What we still need is a strategic plan to set goals to move forward in a more sustainable way,” Rhone said. “That’s the key.”

Collaborative planning

Seven years ago, Rhone began talking with Adela Smith, a vice president and partner at Fairmount Ventures, about Mount Moriah’s needs. Their conversations continued off and on until last summer, when the planning process formally began with the support of the City Managing Director’s Office, which is overseeing a $75,000 grant from the William Penn Foundation awarded in spring 2017 to support the creation of the master plan. The Friends also secured a $25,000 grant from the Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission to fund the cemetery’s ongoing preservation.

In 2015, the city and the courts had established the Mount Moriah Cemetery Preservation Corporation to oversee receivership of the property. Fairmount Ventures is working with the Preservation Corporation, the Friends, experts in cemetery management and cultural landscapes, and other partners in drafting the master plan, Smith said. “We are project manager for the entirety of the plan. But Mount Moriah is special in so many ways, and we are not expert in all of them.”

Those other partners will drive the development of the primary aspects of the master plan.

The ROZ Group is leading stakeholder and community engagement in the planning stages. “There are multiple communities we’re considering in this process,” Smith said. “There’s the Friends group which cares very deeply; the city and its interests; the people who live nearby; and others from around the country who have family members buried in the cemetery. And there are communities we think should care about Mount Moriah who may not even be aware of it.”

Designing a wild place

Overseeing the plan for the landscape is Studio Bryan Hanes. Landscape designer Rebekah Armstrong said the firm is looking at more than a blueprint for adding new horticulture and nurturing established plantings. “Part of our task is to help the Friends group envision what Mount Moriah might become and how the landscape will be a supporting element of that vision.”

The Friends and other stakeholders understand that “they can’t take on the entire site,” Bryan Hanes said. “They have to figure out what’s important,” and the plan will require different approaches throughout the site to achieve their goals.

The cemetery currently includes “some fantastic older specimen trees and unusual species,” Armstrong said, as well as healthy stands of native forest along Cobbs Creek and parkland that is well maintained by Parks & Recreation. But there are also invasive species and dense woody vines that completely obscure areas of the burial grounds.

“Mount Moriah kind of encompasses everything,” Hanes said.

The master plan will include new horticultural elements to replace overgrowth removed in recent years. “If you don’t put something else in, you’ll have something different taking over,” Armstrong explained.

The challenges at Mount Moriah also include diverse perceptions of the cemetery and its role in the community. “People have been using it for different things,” Armstrong said. “Some appreciate the wildness and seclusion. Others want to go there just to visit the graves. There are different expectations of what a cemetery should be.”

Taking the lead on preservation planning is KSK Architects Planners Historians. Philip Scott, KSK principal, and senior architect, said Mount Moriah’s landmark gatehouse is one focus among several elements that need attention.

The temporary reinforcement that is currently supporting the gatehouse is “holding up, but it won’t last forever,” Scott said. “What they did was smart and timely. You have to start with triage and work up to the long-term goal.”

The first step is stabilizing the crumbling gatehouse. But long-term planning will include some form of reuse, which may mean a “stabilized ruin approach,” said Scott. If planners move forward with that approach, the gatehouse will keep its “distinctive and unusual” presentation, while getting the repairs needed to make it usable, Scott said. The iconic structure could be transformed into a stage or a setting for weddings or other occasions. “That would be a next level of use, but it’s dependent on the funding available,” he said. A complete restoration or rebuilding of the gatehouse would cost an estimated $2 million to $3 million, and “at this point, is not realistic,” Scott said. But as a long-term goal, looking ahead 25 years, “it could be.”

Beyond the gatehouse, KSK is looking at how to preserve the cemetery’s perimeter wall, fencing, and the bridge over Cobbs Creek. The planning also will address the resurrection of the monuments and the restoration of the roads and paths through the burial grounds that have disappeared over time. A recent project at Laurel Hill Cemetery revived the old routes and revealed much about the beauty and design of the grounds, Scott said.

The last major hurdle at Mount Moriah, he said, will be reusing the 20th-century, two-story offices off Kingsessing Avenue. Making them operational will help in developing a business plan that generates income again at the cemetery.

The business of death

Identifying the options for resuming cemetery operations is a vital goal of the master plan. The city and state learned of Mount Moriah’s financial troubles about six years ago, but “that was years in the making,” Smith said. “Mount Moriah struggled over the centuries to be a viable business. People don’t think of a cemetery in that way; they think of it as a place to inter loved ones.

“We have to consider what it would take to restore faith in Mount Moriah as a business. What is the timeline for that? When would it be possible to offer space for burials or cremains?” Smith said. “We are absolutely considering options for resuming cemetery operations. But it involves more than putting up an ‘Open for business’ sign.”

Until it can stand on its own, the cemetery will continue to depend on outside funding. “Whatever planning we do, we always consider where the money is going to come from,” Smith said. Unfortunately, “the world of grants for preservation is pretty small.”

The initial grants that the Friends have attracted for Mount Moriah’s preservation will likely help with future applications. Last year the cemetery earned accreditation as a Level 1 Arboretum, a public space with at least 25 species of woody plants. “We go after anything that can preserve Mount Moriah and open the door for funding,” explained Rhone.

The planners also will explore other ways, including community programming, to leverage grants for restoring the cemetery buildings and landscape.

An excellent model is The Woodlands, where educational programs, gardening workshops, tours and other community activities are hosted year-round. “There’s a lot of energy there that gets leveraged for grants for preservation and other goals,” Smith said.

A key consideration for Mount Moriah will be increasing the visibility of the site. Its geographic and historic relationships with its neighbors and other projects, including Bartram’s Garden, the Heinz Wildlife Refuge, and the Philadelphia trails project, may also help bring attention and visitors to the cemetery. “I do think it is possible to make Mount Moriah a destination,” Smith said. “We will certainly want to increase public accessibility and give consideration to more events that can make that happen.”

For now, the visitors are mainly the Friends of Mount Moriah and the individuals and groups who devote weekends to cutting and clearing the acres of graves. “It’s been a beautiful experience in communities coming together to work on the land,” Rhone said. “Friendships have been built at Mount Moriah that would never have been made. It’s been very rewarding.”

The volunteers have made “a lot of progress, but there’s still a lot to go. It’s so massive,” Rhone said. “It will take years to turn this around.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.