Hundreds ‘March in Black’ to shed light on Philly’s opioid crisis

-

People hold signs and photos of friends and loved ones lost to opioid overdoses under the El Thursday for the March in Black that traveled from the York-Dauphin Station to Somerset Station. (Brad Larrison for NewsWorks)

-

Aaron Cruz holds a sign calling for no more overdoses at the March in Black through Kensington Thursday evening. (Brad Larrison for NewsWorks)

-

A casket is carried up Kensington Avenue Thursday during the March in Black in remembrance of those who have died of opioid overdoses in the Philadelphia region. (Brad Larrison for NewsWorks)

-

Donna Morgan, (left), stands with a picture of her daughter Brittany who died of a heroin overdose in May 2017 along with her son Nathan and friend Robin D'Angleo whose son is in recovery for heroin addiction. (Brad Larrison for NewsWorks)

-

Hundreds march up Kensington Avenue Thursday for the March in Black in remembrance of those who have died from opioid overdoses. (Brad Larrisonf or NewsWorks)

-

Hundreds march up Kensington Avenue Thursday for the March in Black in remembrance of those who have died from opioid overdoses. (Brad Larrisonf or NewsWorks)

-

Men stand outside of the Last Stop recovery house as the March in Black makes it's way down Kensington Avenue. (Brad Larrison for NewsWorks)

-

Hundreds march up Kensington Avenue Thursday for the March in Black in remembrance of those who have died from opioid overdoses. (Brad Larrison for NewsWorks)

-

Hundreds gather at Huntingdon Station under The El Thursday for the March in Black in remembrance of those who have died from opioid overdoses. (Brad Larrisonf or NewsWorks)

-

Ashley Babiarz of Northeast Philadelphia holds a sign to honor her brother Michael who died in 2011 of an overdose. (Brad Larrison for NewsWorks)

-

Hundreds gather at Huntingdon Station under The El Thursday for the March in Black in rememberance of those who have died from opioid overdoses. (Brad Larrison for NewsWorks)

-

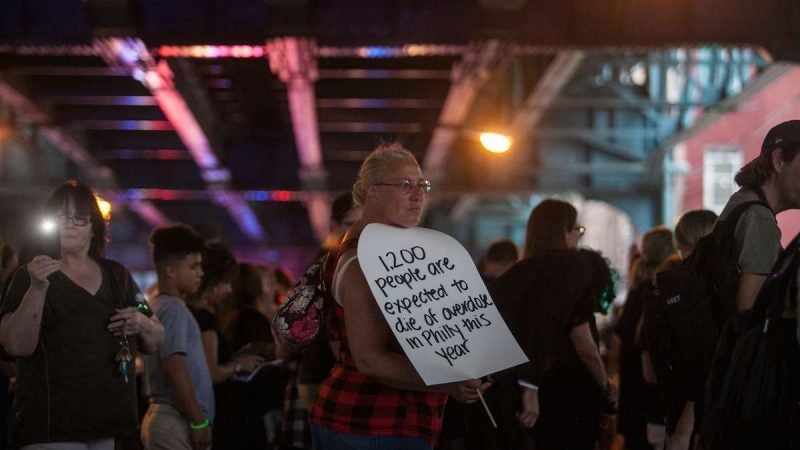

Teresa Force of Lawncrest holds a sign and listens to speakers under The El during the March in Black Thursday evening. (Brad Larrison for NewsWorks)

-

Marchers take a break during the March in Black through Kensington Thursday evening. (Brad Larrison for NewsWorks)

-

Hundreds march up Kensington Avenue Thursday for the March in Black in remembrance of those who have died from opioid overdoses. (Brad Larrison for NewsWorks)

-

Hundreds march up Kensington Avenue Thursday for the March in Black in remembrance of those who have died from opioid overdoses. (Brad Larrisonf or NewsWorks)

-

Hundreds march up Kensington Avenue Thursday for the March in Black in remembrance of those who have died from opioid overdoses. (Brad Larrison for NewsWorks)

-

Hundreds march up Kensington Avenue Thursday for the March in Black in remembrance of those who have died from opioid overdoses. (Brad Larrison for NewsWorks)

-

Hundreds march up Kensington Avenue Thursday for the March in Black in remembrance of those who have died from opioid overdoses. (Brad Larrison for NewsWorks)

-

Hundreds march up Kensington Avenue Thursday for the March in Black in remembrance of those who have died from opioid overdoses. (Brad Larrison for NewsWorks)

-

A sign at the March in Black reads, 'Be nice to drug users! Education Saves Lives!' (Brad Larrison for NewsWorks)

More than 300 people wearing black walked through the streets of Philadelphia’s Kensington neighborhood Thursday night, past some of the city’s most notorious drug corners to call attention to the local toll of the opioid addiction crisis.

Marking International Overdose Awareness Day, the “March in Black” began at the York Dauphin el stop on the Market-Frankford line and ended with a candlelight vigil in McPherson Square.

Organizer Dan Martino said he wanted to bring people to the neighborhood, which has become ground zero in the city’s opioid epidemic, to see the impact of the crisis for themselves.

“My mom was telling me how people used to dress up to walk down Kensington Avenue,” he said. “Now, most people in Philadelphia wouldn’t even drive down this street. So I wanted them to come see for themselves how much work needs to be done.”

Marchers also carried signs shaped like tombstones to memorialize those lost to overdoses, and represented groups from all reaches of the opioid epidemic from first responders to community organizations.

At the Huntingdon el stop, Asteria Vives with Home Quarters and Friends, spoke of her time working with homeless people dealing with addiction.

“We’ve been through a lot because the people we come across, they become like family,” Vives said. “And we have lost a lot of loved ones. [People] ask me how we can make it better. And I believe we can make it better if we can all take a little bit of responsibility for what’s going on instead of pointing fingers at city officials and police officers.”

Among the solutions advocated by those attending were safe injection sites where users can shoot heroin under medical supervision and find access to treatment programs. Others called for needle exchanges, longer stays in rehab and better access to housing.

Joanna Bellinger is a volunteer with Angels in Motion, one of the organizations that sponsored the march. She wants more opportunities and fewer hoops for people struggling with addiction to get help.

“My son needed like twelve chances — and you never know if the last one is going to stick until you’re looking back on it,” she said. “And he’s a functioning member of society because we kept giving him the chances.”

Louis Langlis said he walks through the neighborhood every day for addiction treatment. After losing his best friend to an overdose earlier this year, he always carries the antidote Narcan.

“Ever since his death I’ve been trying to do good deeds,” Langlis said. “I’ve been trying to bring people to get Narcan. I’m trying to see if I can make a difference. I know I can’t change the world by myself, but I’m trying to make a difference and that’s why I’m here with them.”

He’s not the only one. After her sister Valerie died of an overdose, Darlene Davis started keeping Narcan in her purse.

“She was 15 when she picked up heroin and she was 23 when she passed,” Davis said. “She was alone, which sucks. I felt like if I was there it wouldn’t have happened. And I can’t blame myself, but you think about everything when you lose someone that close to you.

“I was clean when she passed,” Davis added. ‘And after she passed I couldn’t take it. And I used again for a few more years. I was living in abandoned buildings — cold winters, hot summers. My grandmom literally picked me up off the street and brought me to my mom’s. She said, ‘I am saving your life.’ ”

Last year in Philadelphia, more than 900 people died from drug-related overdoses. The city is on track to lose 1,200 more this year at an average of 100 per month.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.