How to get kids to read ‘The Grapes of Wrath’ — trust me

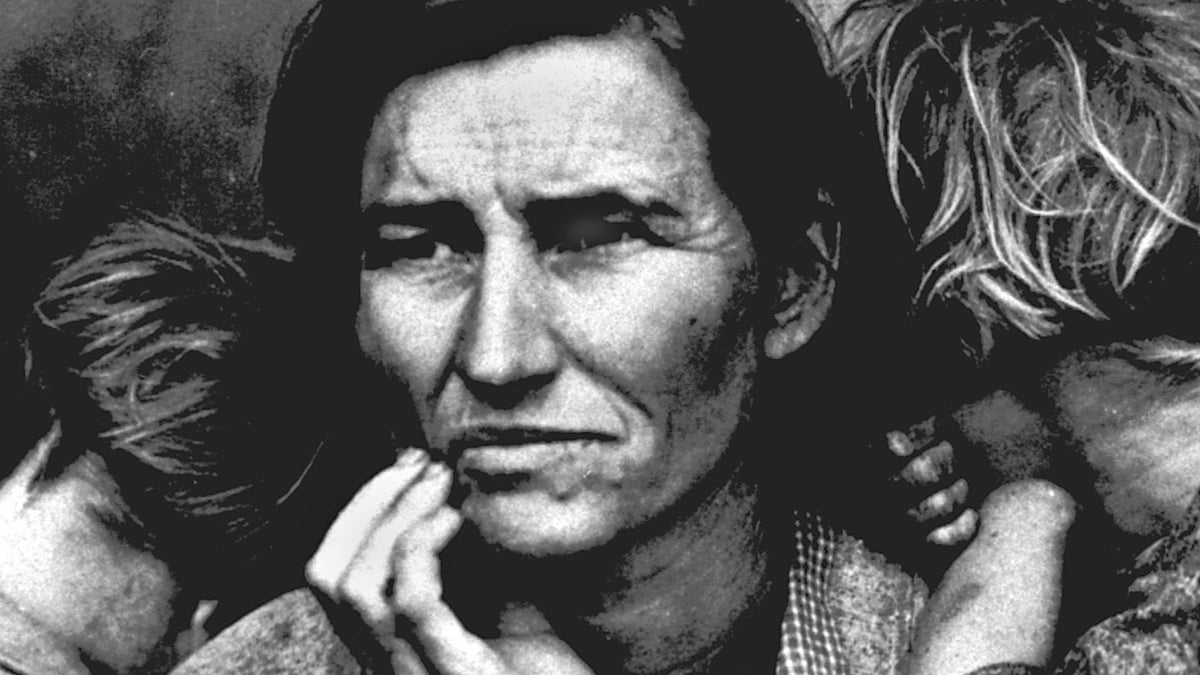

Florence Thompson, 32, and her children are photographed in a camp of destitute pea pickers in Nipomo, central California, during the Great Depression in 1936. (AP Photo/Dorothea Lange, file)

My students must have thought: “Perfect! Watching movies in class! A no-brainer!!!” Imagine their shock when I handed them “The Grapes of Wrath” by John Steinbeck on the first day of class and asked them to read the first three chapters by the next day.

It was senior year, second semester, a challenging time for any teacher. I’m sure that my elective English course “Books to Film” was a draw for students because of its title and brief course description. We were to read novels, plays and short stories and then watch films adapted from them.

My students must have thought: “Perfect! Watching movies in class! A no-brainer!!!” (My students, all girls in the independent school where I taught, frequently spoke in exclamation points.)

Imagine their shock when I handed them “The Grapes of Wrath” by John Steinbeck on the first day of class and asked them to read the first three chapters by the next day.

“But it’s so looonngg! And the print is so small! We thought we were watching movies!!!”

I steeled myself against their sad faces. “Oh, we are going to watch movies,” I said. “We’re going to watch the movie in stages, as we read the book. And we are going to see what themes and characters and scenes in the book became part of the filmmaker’s vision. It’s going to be really cool. Trust me.”

Dour looks of doubt.

Stumbling blocks open up opportunities

“Trust me.” I found myself saying it many more times during our journey through Steinbeck’s masterpiece. Both my students and I felt at times like we were on the long slog across the country with the Joads.

“This is the worst book I have ever read,” one student offered up one day, about halfway in. Several others nodded in agreement. “And it’s way too long.”

“Trust me,” I said. “It will start to grow on you. Just give yourself over to the book. Don’t fight it.”

We forged on at a pretty good clip. After all, I had several more decades’ worth of books and films to torture them with before school ended. I came up with several strategies for “getting through” the dense novel, with its country folk dialogue of 1930s migrant families, unfamiliar to my suburban students’ ears; the rather graphic (I had forgotten how graphic) sexual innuendoes and plain talk of the men in the book; and — most of all — the unrelenting hardships that the Joad family and their contemporaries faced.

Watching the stark black-and-white film — also unfamiliar to them — was disconcerting on many levels, as well: Nothing was blowing up, there was no romantic intrigue, and we spent a lot of time watching the Joads’ broken down jalopy chugging along Route 66.

There were plusses. I asked my students to present short projects as we went through the novel. We looked more closely at Route 66; at migrant conditions then and now; at Hollywood in the 1930s; at Dorothea Lange’s iconic photo of the migrant woman and her children; at the career of John Steinbeck himself; where the novel’s title came from — “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” — which we listened to with a new appreciation, and how Americans reacted to the unflinching portrayal of the nation’s underclass.

Happy ending

Then we came to the ending. I tried to prepare my students a little, without giving away the famous last scene of Rose of Sharon offering her breast milk to a dying stranger, after her own baby has died. No sugarcoating that one.

They had often asked me in the course of our reading and viewing: “Does it at least have a happy ending?”

I usually countered with, “It has an ending that, once you read it, you will never forget.” I was really thinking back to my own experience reading the book at their age, and how I was so stunned by what I read that I burst into tears. It was one of my first experiences of pure and true empathy with “made-up” characters in a book, who at that moment seemed as real as my own family.

There were several comments about the ending along the lines of “How gross!” or “Eeeuuuww!” but mostly the feeling seemed to be one of exhilaration, and even pride, that we had finished it.

I wrapped up our discussion by thanking them for staying with the book and giving it their best. (They really did.)

“You may not have liked the book, but you will never, ever forget it,” I said. “Trust me.”

—

Author’s note: We also went on to read the written work and films based on: “Ordinary People,” “The Descendants,” “Beasts of the Southern Wild,” and “For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow is Enuf.” Finally — joyously ending on the last day of senior year — we watched “Romy and Michele’s High School Reunion.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.