How a West Philly block struck by tragedy became unknowing participants of a traffic study

The concrete slabs on both ends of the block where 7-year-old Zamar Jones was fatally shot remind neighbors of the government’s promises — and struggles.

Simpson Street block captain Derrick Smith says the barriers the city put up to slow traffic are not working. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

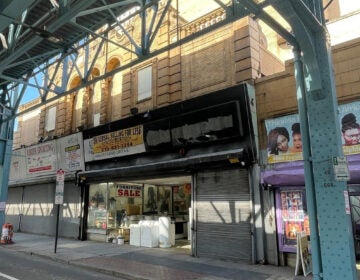

Nothing happens on the stretch of 200 N. Simpson Street without its block captain Derrick Smith hearing about it. One mystery that he hasn’t been able to solve since the fall, however, is the appearance of 8-foot concrete slabs capping the start and the end of the street.

“The first thing came in my mind is, ‘OK, well they’re going to start the process of putting the speed bumps down here,’” said Smith.

Smith and his neighbor have spent months lobbying the city for speed cushions — residents refer to them as bumps or humps. Smith, who knew that the city had to do a traffic study to determine eligibility for the bumps, figured the barriers had to be measuring the speed of passing cars. What he didn’t know is that the study already happened and the barriers are there instead of the speed bumps as part of a new pilot that aims to eliminate the city’s traffic-related deaths and severe injuries. 200 N. Simpson Street is the first block in the city to test the barriers.

While the barriers, which “neck-down” the entrance and exits of the street, suggest progress in the block’s ongoing effort to make the street safer, they signal a breakdown in communication between city officials and those they serve. As a result, the block became the unknowing participant of a traffic experiment.

A tragedy brings slew of promises

Residents of the block insist their inclined street has long been a favorite for reckless drag racing. The strip attracts outsiders who barrel down the narrow road and then loiter for hours on end, according to parents, endangering the dozens of children who live there and like to play in front of their homes when school is out. Block leaders and parents were asking the city for speed bumps when tragedy struck.

After 7-year-old Zamar Jones was fatally struck by a stray bullet while playing on his porch in August, 200 North Simpson Street saw a familiar scene break out. Reporters flooded the block, the city was outraged a child was caught in what was already shaping up to be the most violent year in three decades for the city, and officials showed up, as usual, promising justice.

Among a bevy of requests that could improve the neighborhood’s quality of life, residents asked for their speed cushions — they told lawmakers the streets department had told them they didn’t qualify for them.

Most residents insisted that, at a minimum, speed cushions would make the road safer.

A small group of residents argued that making drag racing harder and putting an end to the loitering, and the neighborhood “drama” that comes with it, could reduce violence. The hypothesis is not supported by all on the block, but it has precedent and adds to the case for the traffic deterrent.

“It shouldn’t have to be that … we had had this tragedy happen last year on our block for everything to come out,” said Smith. “When we were speaking up about the stuff, they was ignoring us.”

‘It does look like we do a bad public relations [job]’

The city did spring into action after meeting with residents in August. The Streets Department said they conducted a traffic study at the request of Councilmember Curtis Jones Jr. in mid-August. The department examined crash data and found no glaring red flags there, said the city’s Deputy Commissioner of Transportation Richard Montanez. An inspector was also sent out to the block for an hour to measure the speeds of passing vehicles.

The inspector recorded nine cars, said Montanez, all within the speed limit. Once again, it was determined the block was not eligible for the traffic deterrent.

“We don’t tend to tell people when we show up,” said Montanez of why the traffic studies come without fanfare. Residents sometimes like to gather around the inspector with the radar gun measuring speeds.

“If you have a large crowd, people tend to slow down because they want to see what the crowd is doing,” said Montanez.

Despite the results of the study, the streets department did act. It installed the cement barricades. Placed at an angle, the barriers narrow the entrance and exits of the street, working as a cost-effective curb bump out — those curb extensions which aim to make pedestrian-friendly streets.

An explanation of the effort never reached Smith or anyone he’s talked to. After WHYY offered an update on the progress the city made and the pilot, residents expressed a sense of betrayal and anger.

“The only thing they’re going to do with them barricades is cause an accident,” said resident Makeeba McNeely, who added the barriers are an eyesore.

Whether the barricades have helped with speeding is up for debate among residents. McNeely said the racing has declined since the installation and worries about a potential crash when a drag racer, unaware of the change, turns the corner too quickly.

Smith said he’s seen cars slow when turning onto the block to avoid scraping their vehicles, only to speed up and try to abruptly stop before they reach the end of the barricade.

The larger frustration for McNeely and Smith is the fact that they’ve remained largely in the dark for the past several months, unclear if the concrete barricades are going to be a permanent fixture.

“I’m not going to disagree that it does look like we do a bad public relations [job],” said Montanez when asked why they didn’t make a bigger announcement or put out a press release when testing the pilot on the block.

For the time being, Montanez said the barriers will remain in place until April when an inspector will go out and track the speed of passing cars with the barriers in place.

Montanez said the department can pay its visit at an hour residents think will yield more accurate results.

“We’re currently trying to finalize this pilot but give us a little time and if you think you think you can add data to it, by all means, we’re willing to listen to you,” he said.

Montanez said he can ultimately only go by what the radar tracks and that often, residents may feel like cars are speeding down a block, when the vehicles are traveling at the posted 25 miles per hour limit.

For McNeely, the response to the block’s request is just another disappointment and she wonders if a whiter, more affluent block would face similar struggles.

“That’s how I feel, it’s a Black community and they don’t want to take care of it,” she said.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.