A history of increased African-American visibility, self-determination in ‘Black Pulp!’

The exhibition at the African American Museum in Philadelphia continues through April 29.

Detail from a promotional image for "Black Pulp!" which uses William Downs' 2013 etching "Power of Fantastic" as a background. (Courtesy of the African American Museum in Philadelphia)

Pulp is a cheap paper that made mass communication possible by allowing newspapers, books, fliers, leaflets, posters, and other ephemera to be printed inexpensively in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Many of the images of black people that white Americans produced and distributed in that era were racist — from Philadelphia physician Samuel Morton’s “Crania Americana” (1839), which attempted to compare skulls of people of different races, to Harper’s Weekly magazine, which took a weak position on slavery and published political cartoons that satirized the periods of Civil War, Reconstruction, and emancipation from 1857 to 1916 with vicious stereotypes.

Black representation in American media was limited to “mammies, watermelon-eating Sambos, coons, pickaninnys, niglets, and jigs,” writes William Villalongo, assistant professor at New York’s Cooper Union School of Art and co-curator of the exhibition “Black Pulp” at the African American Museum in Philadelphia through April 29.

It extended to all forms of mass media. Look no further than Warner Bros. (among other studios) for brutally racist animated representations of black people from the ’20s through the ’70s. An example can be seen in the short film “Coal Black and the Sebben Dwarfs” (1943).

Because pulp was so inexpensive, it facilitated communication within and about the black community. Villalongo writes in the exhibition book that the collection “highlights historical efforts within the medium to rebuff derogatory image culture with exceptional wit, beauty, and humor, to provide emerging, nuanced perspective on black humanity.” The graphic prints from the 20th century Harlem Renaissance and later generations respond to historical racist images by showing each other and the wider world who African-Americans actually are.

Philadelphia has its own black pulp legacy with The Philadelphia Tribune, the nation’s oldest continuously run African-American newspaper, and The Philadelphia Independent newspaper, which ran from 1931 to 1971. Historically the Tribune supported the Republican Party because of its history with abolition, while The Independent regarded itself as being for the masses and supported the Democratic Party. The two papers presented different valid viewpoints and strategies about African-American life.

Villalongo and Mark Thomas Gibson curated the “Black Pulp!” exhibit. Gibson is an artist and associate professor at Yale who works primarily in narratives of the African-American male living in our society. He said he was moving from crisis to readjustment when the murder of Eric Garner and the birth of the Black Lives Matter movement changed his perception of what he had to do with his work.

“I began to think of my work less as a museum object spacing and more as a public object spacing,” he said. “A viewer that may have similar issues that I may have, it’s nice when an institution responds to it. But when I see someone on the street or a kid that saw a piece that I did, that is kind of humbling.”

The Harlem Renaissance

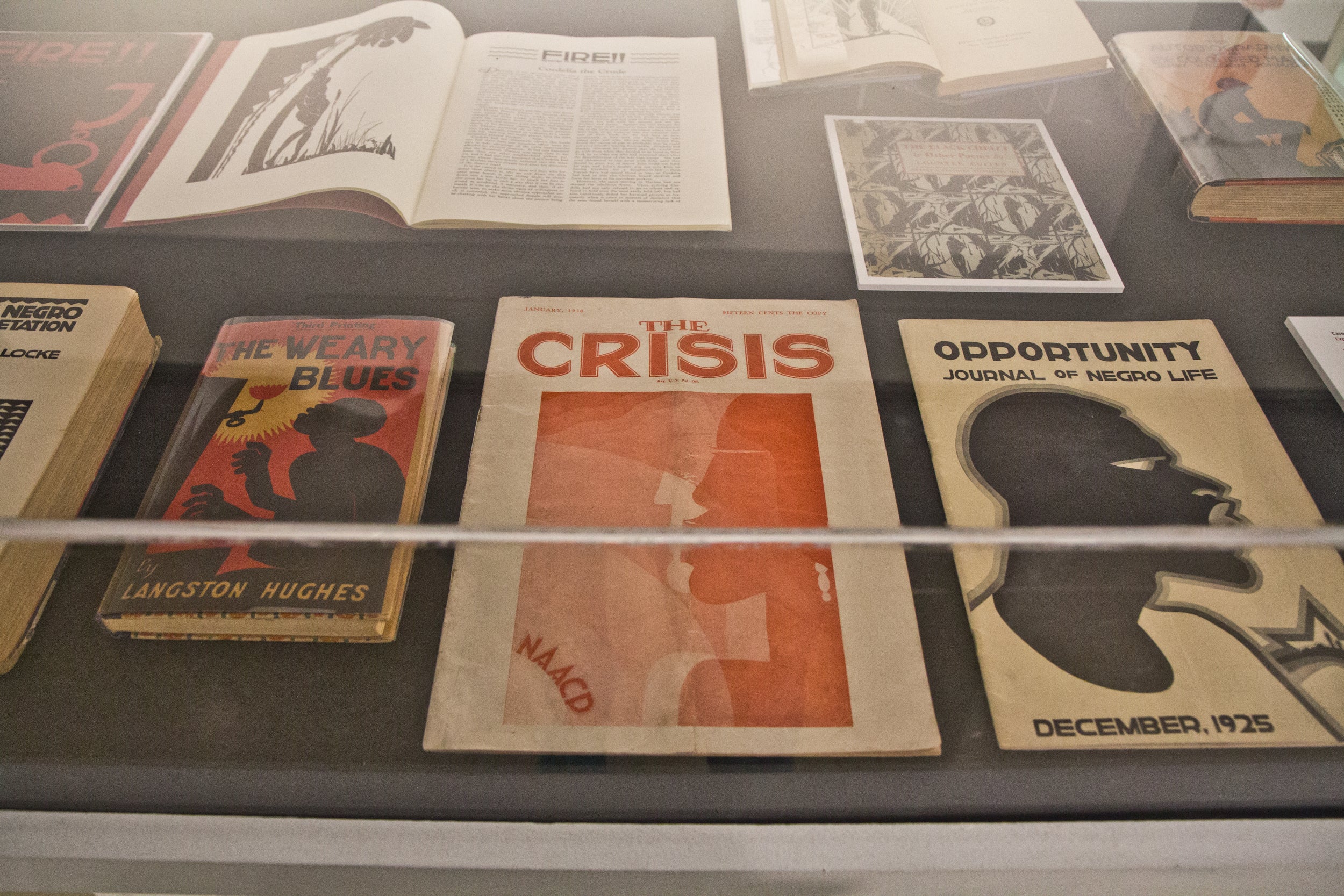

“Black Pulp” starts with the art deco and art nouveau stylized Harlem Renaissance images used by NAACP’s magazine The Crisis, the Urban League’s Opportunity: Journal of Negro Life, early 20th-century black books such as “The Weary Blues” by Langston Hughes, “The Black Christ and other Poems” by Countee Cullen, and “The Blacker the Berry” by Wallace Thurman.

Even in this early period there were arguments within the Renaissance about how the black community should be portrayed. W.E.B. Du Bois, who edited The Crisis, wanted a very dignified portrayal that demonstrated the achievements and respectability of the Negro community, while others such as Wallace Thurman, who edited Fire!!, and writer Zora Neale Hurston presented stories of sexuality (heterosexual and otherwise), prostitution, and people who spoke with Negro dialects.

Du Bois allegedly called Fire!! “vulgar.” These differences were the precursors of the modern arguments between respectable middle-class blacks and Superfly blaxploitation, continuing through this era with Bill Cosby’s comments against rap and hip-hop culture, arguments about how the black community presents itself, and who chooses the images for whom.

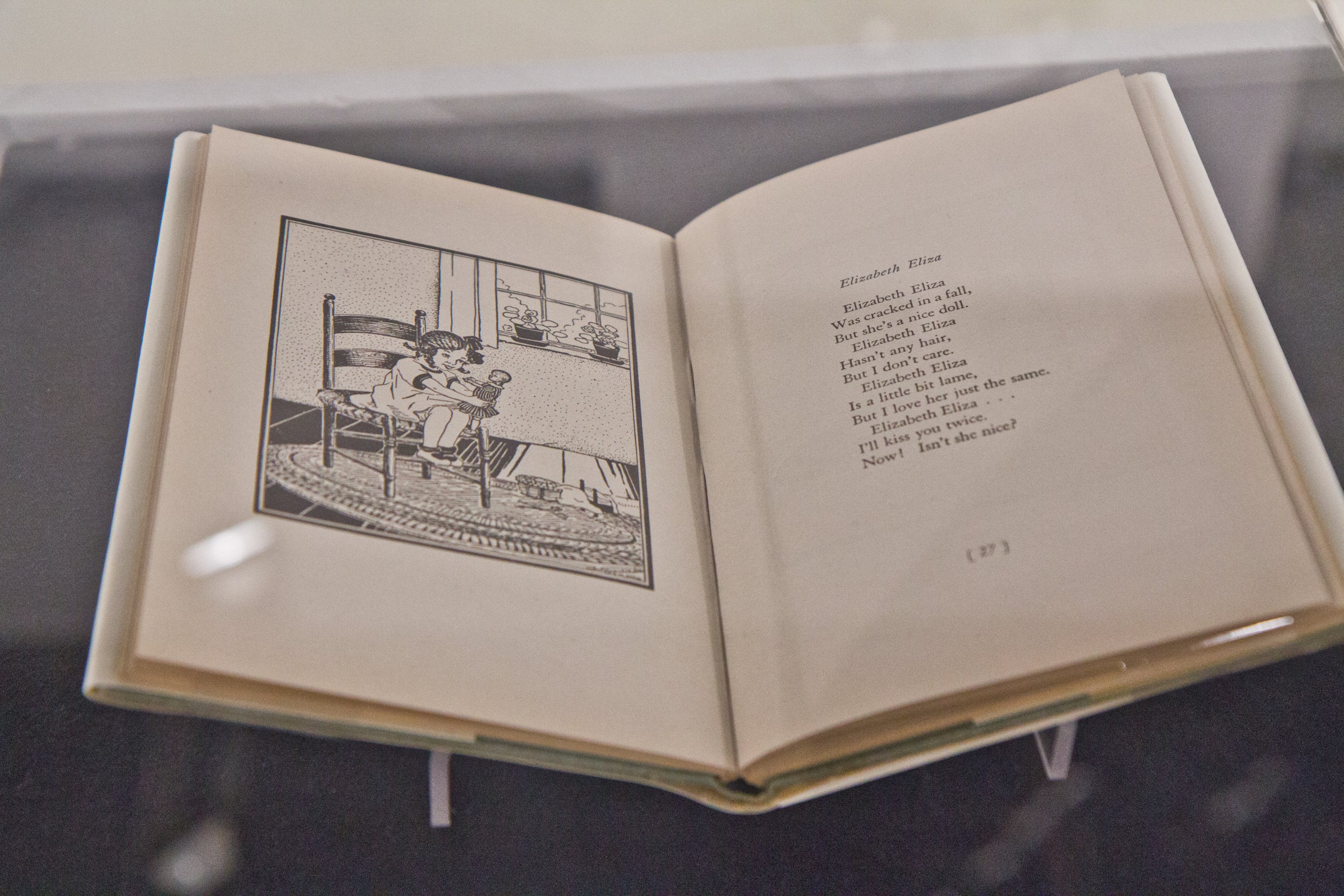

In the 1930s, Loïs Mailou Jones illustrated African-American children’s books, called “Women Builders,” about Negro women building institutions, written by Sadie Iola Daniel, and “The Picture-Poetry Book” by Gertrude Parthenia McBrown has beautiful renderings of black children, using limited color, making the dust jackets less expensive to print. African-American children’s books were nonexistent at the time, so this normal act of creating a children’s book with drawings of black children was radical. Even when I was in elementary school, I didn’t have school books with people of color in them.

Cartoons and comics

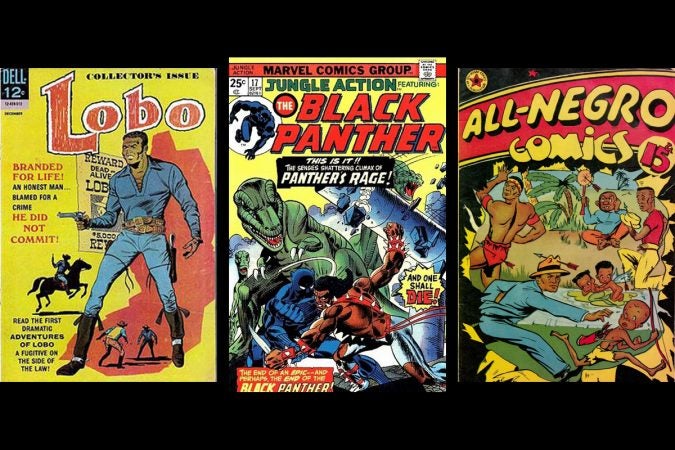

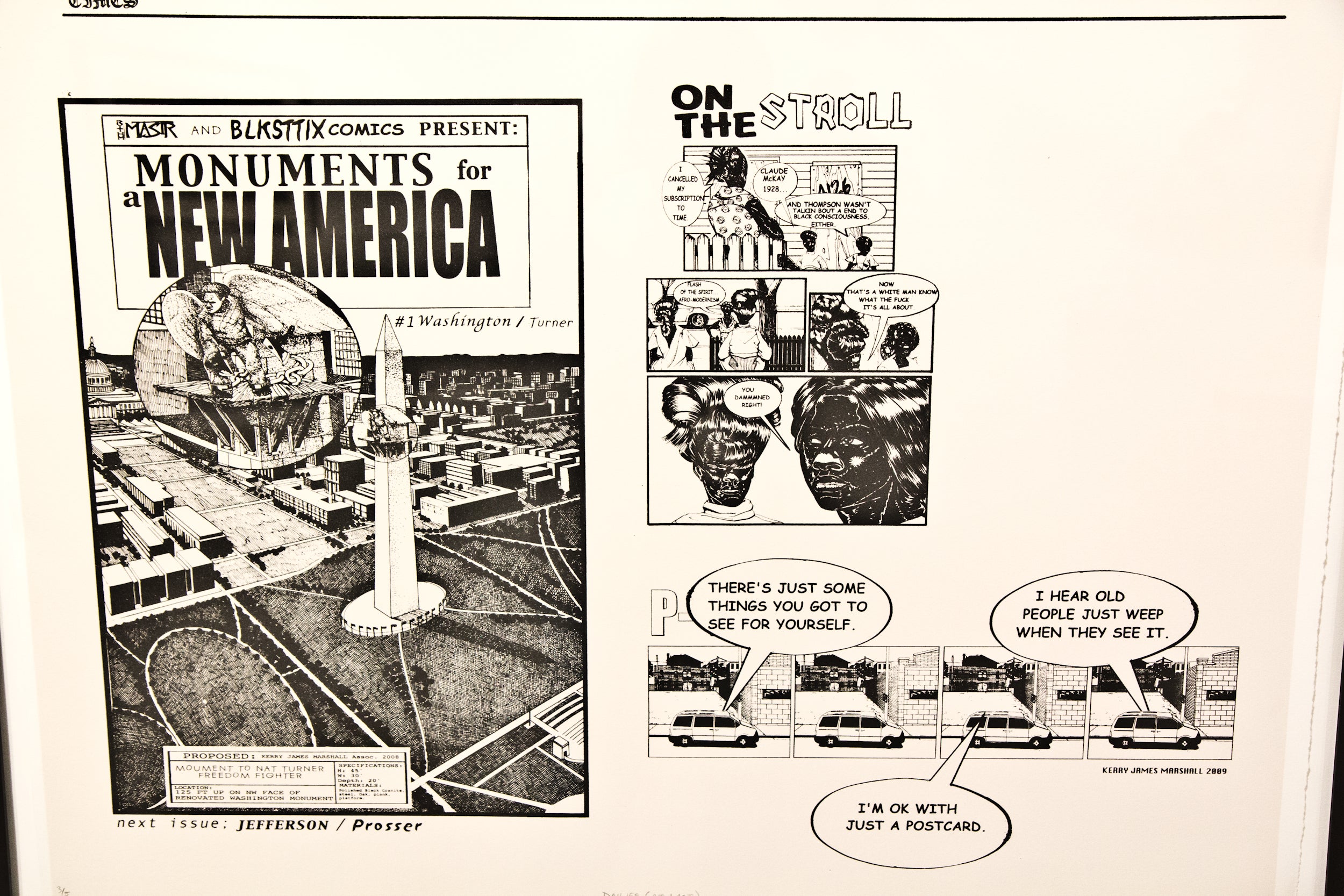

The exhibition is especially timely with the opening of the film “Black Panther,” based on the Marvel comic book character introduced in 1966. Black Panther was the first black superhero in American mainstream comic books.

It was significant for Gibson to see people like himself represented in comic books. “I’m 38, and thinking about what comics meant to me, I would analyze the black characters to see if they are believable,” he said. “That wasn’t the same as with white characters.”

Gibson was impressed with the identity of the character. “He’s a black king from a country that has never been conquered by colonialism.”

Previously, comics with black main characters or by African-American artists were often restricted to a Negro audience. “Torchy in Heartbeats” is a serial about the romantic and work life of a beautiful young Negro woman in the 50s. “All-Negro Comics” (1948) was an anthology comic book that included “Dew Dillies,” about baby Negro angels. In 1965, Dell published “Lobo,” a collector’s book about a black cowboy fugitive.

Billy Graham (not that Billy Graham) created black action cartoons for Marvel in the ’70s such as “Luke Cage: Hero for Hire” and “Jungle Action,” Black Panther’s first starring series.

Despite these gains in visibility, black characters in mainstream comics often continued to be one-dimensional. Dwayne McDuffie, before creating “Static“ for Milestone Comics (now published by DC), critiqued Marvel’s presentation of African-American superheroes by sending a satirical proposal to the publisher for a series called “Teenage Negro Ninja Thrashers,” in which a team of teenage black guys find skateboards with super powers.

It was often difficult to present black characters to a mainstream comic audience. Al Fieldstein (writer) and Joe Orlando (artist) created “Judgment Day,” a science fiction story for EC Comics in 1953. In the last frame, the astronaut is revealed to be a black man.

“EC was a brand of horror and scientific fiction. You could do things in comic books that you could not do in newspaper strips because of different markets,” said Gibson.

A judge on the Comics Code board became incensed that a black man was shown in a powerful position and demanded that the image be removed. Co-editor Ed Gaines hung up on the judge.

Oliver Harrington created an illustrated version of Richard Wright’s novel “Native Son” for publication in black newspapers in the ’40s. An editor asked readers to vote on whether to continue the controversial series, and it was cancelled.

Racial and political symbolism

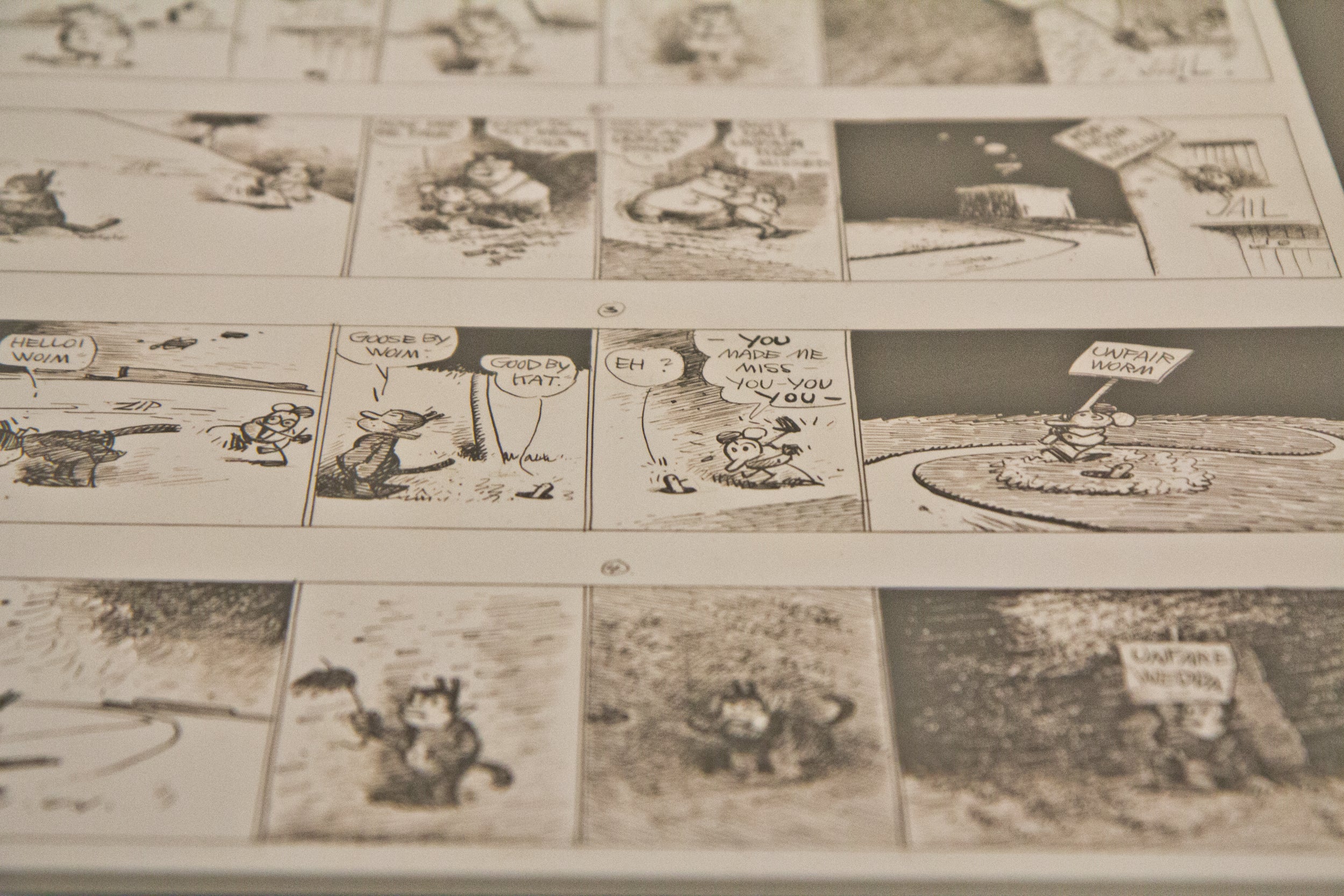

Black comic artists themselves had to deal with racism in their lives and their work. Many people are not aware that George Herriman (a favorite of Gertrude Stein and Picasso, according to art critic and academic Robert Storr), who created the influential cartoon “Krazy Kat” was a black man. Herriman, born in 1880 and active during the first half of the 20th century, was very light-skinned and often wore a hat to conceal his curly hair.

“Krazy Kat” is about a black cat who has unrequited love for the white mouse, Ignatz. The frustrated mouse often pelts Krazy with bricks, which Krazy takes to be a sign of affection. A white police dog, Officer Pupp, who loves the cat, occasionally arrests Ignatz to protect Krazy.

In one strip, which Gibson says they were not able to get from the Library of Congress, Krazy falls into white paint, and Ignatz suddenly falls in love with the cat. It was one of a few instances where Herriman changed a character’s color, with the effect of changing another character’s attitude.

“Some people make a huge point of [the racial symbolism] and some don’t,” Gibson remarked. “The situations that the characters find themselves in compare to racist cartoons. ‘Krazy Kat’ is about humanity, about love and desire, and about how sometimes those things don’t meet. The conflict is their differences, that is highlighted by the actual violence aimed at the cat.”

Actually, people who are in love with people who are toxic to them is not unusual and happens regardless of race. This is all very deep for a cartoon I didn’t think about as a child.

Political subjects were frequent pulp topics. Owen Middleton drew dramatic charcoal cartoons about the trial of the Scottsboro Boys, with a white judge hovering a noose over the bench at the defendants, and protesters at the window of the white judge’s chambers holding signs that read “Free the Scottsboro Boys.” Elton C. Fox created a poster during World War II for NAACP Wartime Conference for Total Peace that compared Jim Crow to the Nazis and Japanese fascists. Ollie Harrington in his “Dark Laughter” series drew a cartoon in 1960 with two black boys in front of a whites-only inn. One says to the other, “My daddy said they didn’t seem to mind servin him on the Anzio Beach-head. But I guess they wasn’t getting along so good with them Nazis then!”

Also on display is a satirical depiction of the U.S. dollar bill from an unknown artist imagining segregationist Alabama Gov. George Wallace as “ruler” and Lurleen, his wife, as treasurer. The piece resembles a turn-of-the-century racist ad, featuring “Ouwa Own Wattamellun Jake,” a black boy eating watermelon and saying “Uhm, dat sho is good, Boss. Yassuh!”

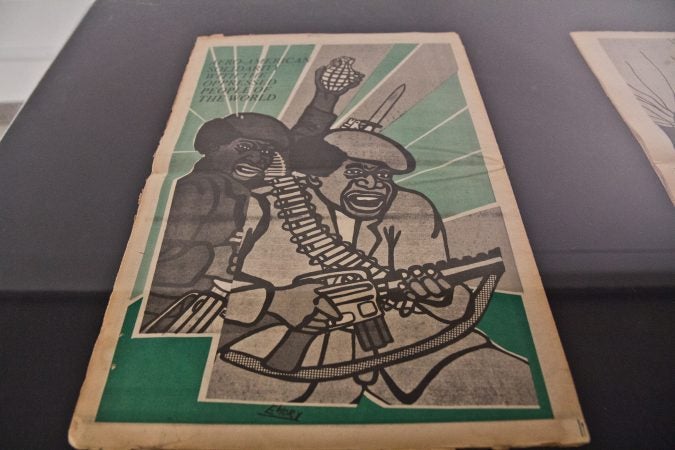

Emory Douglas created bold images for the Black Panther Party in the late ’60s using a thick black line. “Black Pulp!” features an edition of the Black Panther Party Newspaper with the article “Against Fascism” accompanied by his images of two lynched black men and police attacking demonstrators. “Counter Attack” from the New Haven Panther Defense Fund has an image of Huey Newton centered below an image from the 1970 Kent State shootings showing National Guardsmen pointing guns at demonstrators. The caption is a quotation from Mao Zedong: “We are advocates of the abolition of war, we do not want war…”

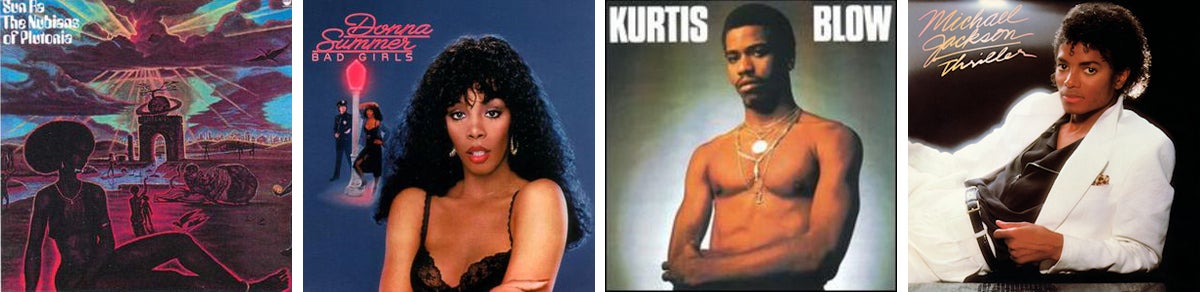

Images from popular culture are also curated for the collection. Record album covers from Sun Ra’s “The Nubians of Plutonia” (1966), Donna Summer’s “Bad Girls” (1979), Kurtis Blow’s “The Breaks” (1980), and Michael Jackson’s “Thriller” (1982) are presented as iconic images of the era.

Art by African-Americans is still treated separately from mainstream art, so various contemporary visual artists are also presented. Renee Cox’s print “Chillin with Liberty” (1998) shows a striking, beautiful black woman in thigh-high patent leather boots and dreadlocks sitting atop the Statue of Liberty’s crown.

Kerry James Marshall’s silkscreen “Dailies from Rythm Mastr” (2010) is a series of black-and-white graphic panels from a comic book about a black superhero.

“Black Pulp!” has been on tour, with stops that included the Edgewood Gallery at Yale University and the International Print Center in New York City, before coming to the African American Museum in Philadelphia.

I asked Gibson how the exhibit changed from showing to showing. He said the “level of refinement changed. I think when you are making or curating something, it goes through stages where you have to find the material and then you have to think about in the space with the other material in the exhibition … Some pieces are on loan and you have to put them in a state of rest. They can’t be on view all the time. Locations have to pass certification, and they have to be properly treated regarding humidity and light levels. We want these pieces to be available for other generations.”

—

Cei Bell is the recipient of the 2015 Leeway Foundation Transformation Award.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.