Timeline: A history of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in Philadelphia

In May 2020, PBS broadcast a groundbreaking five-part documentary series called Asian Americans that chronicled the contributions and challenges of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPIs) throughout our nation’s history. This was a significant milestone for AAPI representation in public television and an excellent educational resource unto itself. Acknowledging the rich untold AAPI history in Philadelphia, WHYY then began work on a local series – Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders: A Philadelphia Story.

From the initial research stage, Japanese American media scholar and historian Rob Buscher was brought into the series as a consultant. To help guide the series production team as they developed episodes with thematic correlations across time periods and communities, Rob compiled a consolidated historical timeline from various community history sources in the Greater Philadelphia region. The timeline is a good resource for general education on these subjects, and makes an excellent companion piece to the series by providing context and granular detail on specific events referenced in each episode.

Spanning from the late 1700s to present day, the timeline is divided into six periods based on legislative context, immigration trends, and overarching narratives that characterize the experiences of the AAPI community in each era. Given the exceptional diversity of these communities, the production team acknowledges that not all of the events included will reflect the lived experiences of all members of the AAPI demographic. However, we hope this will aid others both within and beyond the AAPI community to better understand the historical trends experienced by these communities at-large.

The following is a brief synopsis of each time period represented in the timeline. A more comprehensive timeline is available here.

1700s to 1882

Philadelphia was the second largest city in the British Empire when the Revolutionary War was fought. Given the role that Britain’s East India Company played in empire-wide commerce and trade, it is highly likely that South Asian sailors were present in the busy port city even before the Federal Period. After the Revolutionary War, the city continued to build on the naval trade routes to Asia. Prominent Philadelphians like Stephen Girard and Benjamin Chew made fortunes from the “Old China Trade.” Bringing silk, tea, and other Chinese goods into the local market, Girard and Chew also engaged in opium smuggling to supplement their fortunes, which contributed to the destabilization of Imperial China in the decades prior to the Opium Wars.

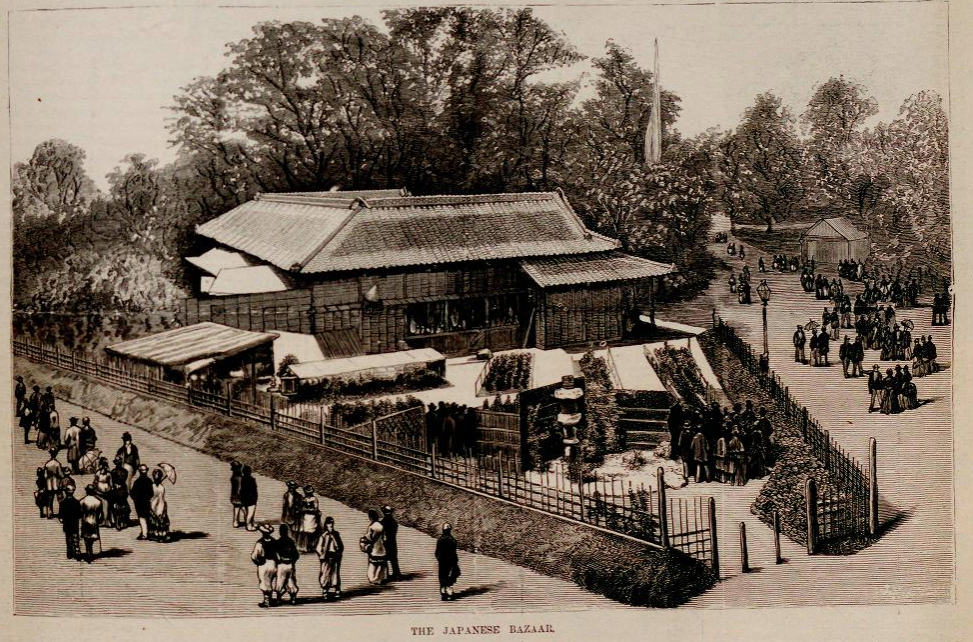

From the 1830s onwards, many Philadelphians developed an interest in “oriental curiosities” exemplified by limited exposure to East Asian culture through traveling exhibitions and Nathan Dunn’s Chinese Museum that formerly stood at present day 9th and Sansom streets. Highly sensationalized exhibits like these catered to Western expectations of Eastern fantasy, profiting from orientalist stereotypes they would ultimately perpetuate within the broader culture. Later at the 1876 Centennial Exposition hosted in present day Fairmount Park, the Japanese Bazaar, Chinese Exhibit, and Filipino Exhibit (included in the Spanish Pavilion) introduced average Philadelphians to East Asian design aesthetics and retail goods.

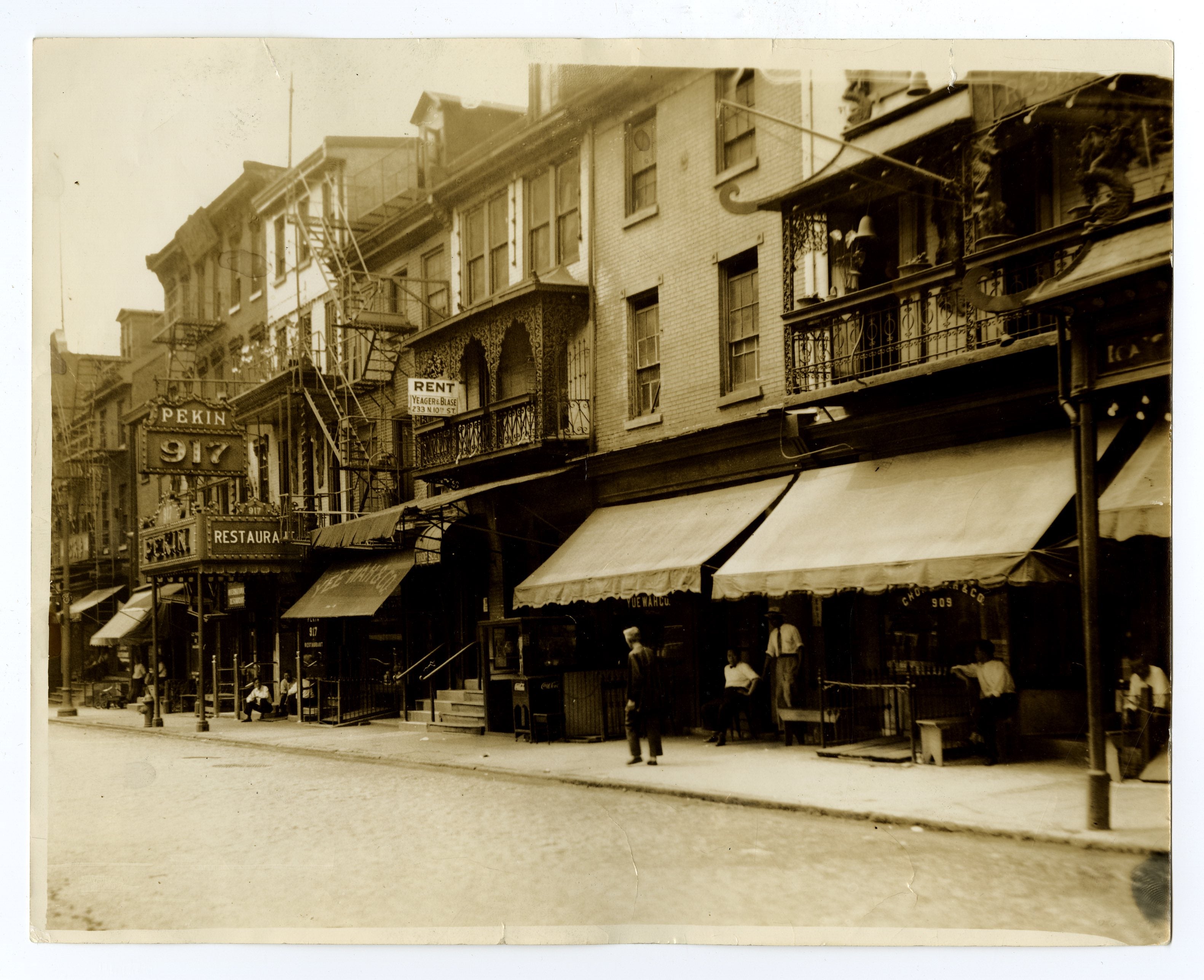

That same year Philadelphia’s Chinatown was first recorded at the 900 block of Race Street, which was largely populated by Chinese bachelors who operated laundries or worked in nearby factories. Most of these men came to Philadelphia fleeing anti-Chinese violence in the Western states. The anti-Chinese sentiments in California and elsewhere in the West would influence Congress to pass the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, which enacted a ten-year moratorium on Chinese immigration that was extended indefinitely in 1892. After the Chinese Exclusion Act, city police and health department targeted Philadelphia Chinatown with a wave of evictions and business closures, reflecting national sentiments of that time.

1882 to 1924

On a national level, this time period encapsulates a major departure in US foreign policy from isolationism to expansionism, and back to domestic isolationism by the time that the Johnson-Reed Immigration Act of 1924 was written into law. Starting with the 1893 overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy and subsequent US annexation of Hawaii in 1898, the US military and business interests began moving westward across the Pacific. Following the 1898 Spanish-American War, the US formally annexed the Philippines and Guam, and soon after added American Samoa to their growing list of Pacific territorial possessions in 1899.

As a result of these expansionist policies, colonial subjects began immigrating to Philadelphia in small numbers from each of these territories. Philadelphia’s Filipino community was first established at the turn of the century, many arriving during or immediately after the Philippine-American War. After the conflict ended in 1902, nearly a hundred Filipino students were sent to Philadelphia to study medicine, some returning to the Philippines and others settling in the region. A number of Filipino doctors and nurses who did immigrate back to the Philippines would later return during the 1918 Influenza Pandemic to help Philadelphia manage its public health crisis. In addition to the Filipino students, dozens of East and South Asian students began enrolling in local universities as early as the 1880s increasing in numbers with each decade.

The end of this period is characterized by anti-imperialist protests such as the Korean Independence March in 1919, when hundreds of Koreans marched through the streets of Philadelphia to raise awareness about the Japanese Occupation. A group of Indian revolutionaries called the Ghadar Party also operated in the region during this time. Protesting British imperial atrocities, several hundred Indian Sikhs marched alongside a crowd of Irish republicans on St. Patrick’s Day in 1920. This period ended with increasingly hostile anti-immigrant legislation that reflected a growing xenophobia in the aftermath of World War I. With the passage of the Johnson-Reed Immigration Act of 1924, the US closed its borders to further immigration from Asia-Pacific and the Middle East, which drastically slowed Asian population growth in Philadelphia until 1965 when nationality quotas were abolished from the immigration system.

1924 to 1965

Although this era saw the exclusion of new Asian immigration to the United States, existing local communities continued to procreate and others from outside the region would resettle in Philadelphia. Despite the relative stagnancy in population growth, Philadelphians showed a growing interest in cultural education and exchange with East Asia in particular during this period. By the late 1920s the Philadelphia Museum of Art and Penn Museum began acquiring architectural elements and other art objects to display in their Japan and China galleries.

Amid Imperial Japan’s military aggression in China throughout the late 1930s, Chinese Americans assumed a more sympathetic position in the eyes of many Americans. In 1939, Archdiocese of Philadelphia began building the Holy Redeemer Chinese Catholic Church and School, which opened in 1941. That same year Chinese Christian Church and Center also opened in Chinatown, bringing many resources into a community that had previously lacked outside investment. The US formally allied itself to China after Imperial Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, and two years later the Magnusson Act of 1943 restored immigration privileges in limited numbers from China. Another result of the Second World War, Japanese Americans living on the West coast were subject to forced removal and mass incarceration throughout the war years in American concentration camps. In the aftermath of their detention, approximately 7,000 Japanese Americans resettled in the Greater Philadelphia region from 1942-1947.

The postwar era saw many changes in US foreign policy with the start of the Cold War that once again resulted in China, and by association some Chinese Americans, being treated with suspicion after the Communist Revolution of 1949. In 1952 the Immigration and Naturalization Act was passed, which for the first time allowed Asian immigrants to become naturalized US citizens. Spurred into action by the civil rights movement sweeping the country, local Japanese and Chinese Americans joined the fight for Black Liberation, participating in freedom marches and Black voter registration. As a result of the allyship shown by local Asian Americans and other immigrant rights activists, African American civil rights leaders began advocating for an end to the racially restrictive immigration quotas that ultimately resulted in the Hart-Celler Immigration Act of 1965.

1965 to 2000

After the Hart-Celler Immigration Act was enacted, large-scale immigration from Asia resumed for the first time since 1924, leading to significant population growth throughout this era. Although the Immigration Act did away with national quotas, a new visa system was put into place that prioritized immigrants from wealthier backgrounds and highly educated individuals who worked in STEM fields. Philadelphia saw its first major influx of South Asian immigrants from India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh during this era. Complicating matters further, tens of thousands of refugees from Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos also began resettling into the Greater Philadelphia region during the late 1970s – early 1980s. Southeast Asian entrepreneurs established themselves along Asian business corridors on Washington Avenue and South 7th Street. Newer immigrants from South Korea, China, and Bangladesh also began establishing themselves in neighborhoods like North 5th Street, Port Richmond, and Upper Darby during this era, drastically reshaping the demographics of each neighborhood.

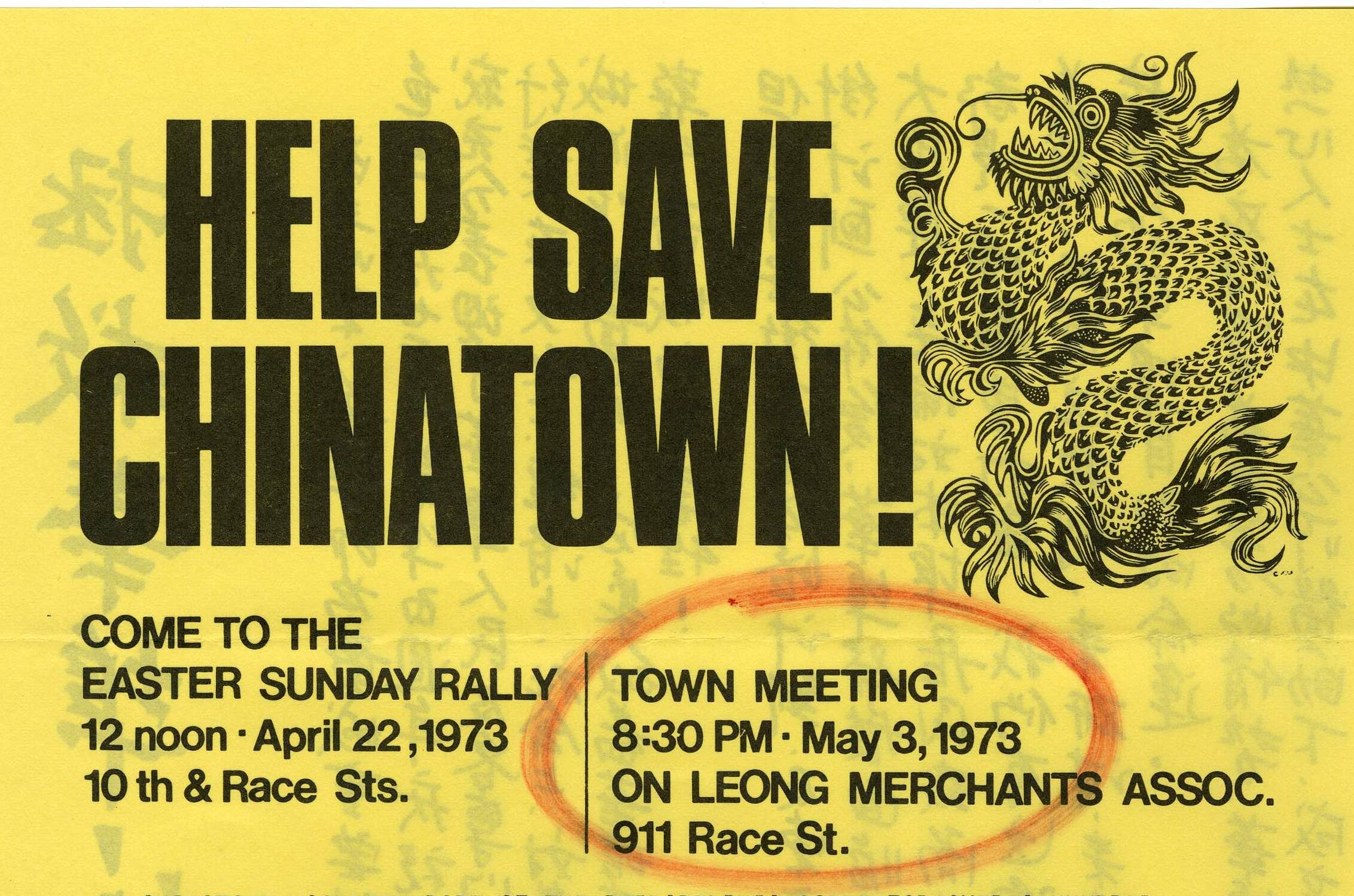

While new immigrants and refugees struggled to find their place in the city, the multigenerational descendants of the earlier waves of Asian immigration began finding their voice politically in this era. Amid nationwide urban renewal campaigns of the 1950s-1970s, Philadelphia Chinatown found itself split in half by the Vine Street Expressway. This experience galvanized Chinatown business owners and community leaders, along with youth organizers of a younger generation who together founded the Philadelphia Chinatown Development Corporation to stand up to the city planners and prevent future eviction attempts. Japanese Americans became increasingly vocal about their own mistreatment during WWII, with several high-profile leaders in the national campaign for Redress living in the region.

By the year 2000, Philadelphia’s AAPIs accounted for nearly 5% of the total city population. Compared to 1990 and 1980 census data that recorded the AAPI population as a mere 2.7% and 1.5% respectively, this period demonstrates enormous population growth at a scale that was previously unseen both locally and nationally. As subsequent waves of immigrants and refugees settled in the region, AAPI communities developed a vast infrastructure of community service organizations, activist groups, arts movements, and ethnic studies curriculums that continue to serve the AAPI communities today.

2000 to 2019

In the past two decades AAPIs have become increasingly visible in all areas of life in the city of Philadelphia. Building on the community infrastructure that was established during the 1980s-1990s, this period marked a departure from individual ethnic communities organizing separately. New initiatives were developed from the early 2000s onwards to consolidate Philadelphia’s AAPI communities as a multi-ethnic coalition. Although limited efforts had been made earlier to establish cooperation among various Asian ethnic communities through professional organizations, this work began in earnest when AAPI advisory commissions were established by the Mayor’s and Governor’s offices.

Many existing AAPI community organizations and movements also came to a maturation point in this period, building both institutional framework and broad-based support for AAPI issue advocacy among the broader public. Anti-Asian bias incidents continued throughout this period, but the community increasingly responded through direct actions, making their voices heard through protest and other means of public discourse. Although most multigenerational Asian Americans had been highly involved in local politics since the 1960s, non-partisan voter registration efforts and naturalization initiatives have resulted in higher voter turnout among newer immigrant communities with each election cycle.

In the last two decades, age demographics have also begun to shift away from a super majority of Asian immigrants to include more second and third generation Americans among the local AAPI community. Born and raised in the US, these multigenerational Asian Americans are fully acculturated to American popular culture, business, and politics, and have increasingly brought this knowledge into local movements that have historically been immigrant led. Some of the more recent immigrant and refugee communities remain isolated due to limited English proficiency and general lack of capacity as they navigate resettlement into this region. However, greater efforts are being made by Pan Asian service organizations to provide access to city and community resources that were unavailable to previous generations of Asian immigrants.

2020 COVID-19 Pandemic to Present

As a direct result of political rhetoric early in the COVID-19 pandemic that blamed China for the US public health crisis, AAPIs have faced an intense amount of anti-Asian hate both locally and nationally. These narratives are consistent with past examples dating back to the early period of Chinese immigration when Asian immigrant communities were frequently scapegoated for outbreaks of disease. Although the city of Philadelphia took steps to counter anti-Asian bias in the first months of the pandemic, dozens of high-profile instances of violent crimes and hate speech have plagued the local AAPI communities over the past two years.

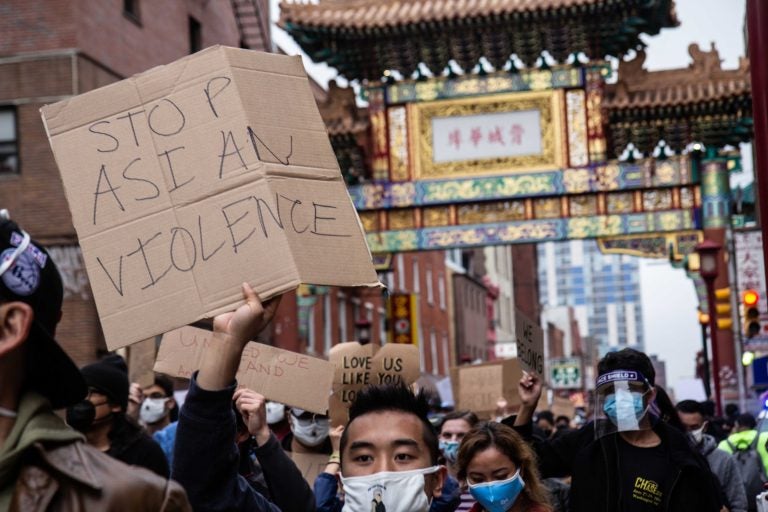

However, there is now a greater unity among many AAPI advocacy groups and community organizations that was brought about by the need for collective response to the crisis as East and Southeast Asians have been targeted indiscriminately regardless of their ethnicity. In the aftermath of the Atlanta Spa Shootings on March 16, 2021 in which six East Asian women were killed, AAPI community members organized public protests and marches on a scale that has not been previously witnessed in the city of Philadelphia. While the threat of violence remains a constant concern of the AAPI community, in one sense this current crisis has galvanized public support around the local community and provided opportunities for greater awareness about the myriad issues AAPIs face today.

Watch or stream Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders: A Philadelphia Story beginning on April 6th, 2022 at 7:30PM on WHYY.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.